2.When to use the Toolkit

This toolkit is designed in a modular fashion that follows an established process, so it can be used from the onset of designing an LME project. Yet, it was developed in a way that also allows users to pull individual tools and elements to meet specific needs without having to work through the entire process. This toolkit will be most useful as LME conveners begin discussions on a new project. However, the idea of this approach is to engage stakeholders throughout the entire process, so conveners could refer to this document for guidance on specific issues at any stage during a particular series of interventions.

This toolkit has been developed with the understanding that many of its users will be LME practitioners; therefore, it is closely aligned with the Large Marine Ecosystem Scorecard and the Capacity Development Guide for LME and Coastal Ecosystem-Based Management. LME users are advised to begin by completing the

LME scorecard first as many actions and interventions will be identified through that process, which can later benefit from following the process presented in this guide.

2.1 Stakeholder participation in environmental governance

2.1.1 Environmental governance in the LME context

Environmental governance refers to the various policies, regulations, rules, actions, and affairs, both formal and informal, deployed to ensure the sustainable delivery of environmental goods and services to advance social and economic goals. Governance not only involves governments and their agencies, it includes civil society (NGOs, resource user groups, community members), academic and scientific institutions, and the private sector. Environmental governance is often organized around thematic and/or spatial issues (e.g. fisheries and biodiversity management; watershed and coastal zone management). It is grounded on the notion that natural resources are public goods, that is, they are non-rivalrous resources and attributes we all benefit from equally (such as clean water and stable biodiversity), while it recognizes that natural resources have value for human well-being, so they must be protected from destruction and degradation.

In the LME context, governance must be ‘encompassing’, meaning it should go beyond simply assessing and monitoring ecosystem function to integrate scientific knowledge and throughout project implementation to guide decision-making. Leaning on the principles of adaptive management, LME governance ought to be cyclical in nature starting with gathering and analyzing key information, institutionalizing data driven decision-making, implementing fact-based management actions, and evaluating the consequences of interventions. As such, LME projects should invest in cost-effective measures to address information, data, and knowledge gaps that can inform management, while providing measurements of impact and progress against pre-established objectives. Also, understanding the LMEs are by definition multi-scale management interventions, LME governance efforts should prioritize harmonizing policy and management actions across jurisdictions, beginning by distilling global agreements (ex. Law of the Sea), coordinating regional initiatives, strengthening national regulatory frameworks, and developing local management capacity (Mahon et al. 2009).

Given the varying spatial and temporal scales of environmental goods and services produced within the boundaries of LMEs, governance is usually approached within the scales of jurisdictional decision-making where specific issues or concerns exist. For example, agricultural run-off and marine pollution tend to be localized issues, so they are managed, for the most part, within the ecological and jurisdictionally boundaries of the issue (local scales).

At the national level, governance focuses on regulatory frameworks and enforcement of laws, such as designation of protected areas and management of key habitats and species. Benefits such as fisheries, which are highly migratory, are governed by regional bodies, as is the case with Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). And at the highest levels of governance, there is management of global issues, such as climate change, which requires a coordinated global response; thus, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the leading treaty ratified by most countries whose objective is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations to prevent anthropogenic interference with the climate system.

This is not to say that efforts shouldn’t be aligned — quite the contrary — and this is precisely the fundamental role LMEs can play in marine resource governance. Because many marine environmental management issues permeate across political and jurisdictional boundaries, LMEs can align environmental governance efforts across management scales, from the local community and national levels, all the way to the regional and global levels, both through bilateral (two countries) and multilateral (many countries) initiatives. Thus, by fostering and implementing encompassing ocean governance based on adaptive management, LMEs can bridge multiple management scales and bring together multiple stakeholders, all of which are indispensable components to cultivate sustainable ocean and coastal resource management.

2.1.2 Right-sizing the activities

One of the main challenges in environmental governance is achieving trust between and among the large number of players often involved in natural resource management. To overcome this barrier, it is often more effective to organize smaller management groups around specific issues that are “nested” within governance structures of larger scope. This “multi-level” governance, which is an aggregation of smaller groups, allows for autonomy and in-group trust building, while assuring members that their efforts are linked with initiatives at larger scales3. This implies that nested governance groups are only handling a few tasks specific to their level of management.

A good rule of thumb, however, is that as much as possible is done at the lowest level of governance since that is often where the resources and their users are interacting most directly. At this scale, resource co-management is regarded as the governance standard, which is where community resource users, governments, and businesses “share the responsibility and authority for decision making over the management of the natural resources” (Pomeroy and Rivera-Guieb 2006). When a co-management unit engages in activities and behaviors that affect other co-management units, governance of these resources should be assigned to higher management levels, often state or provincial levels. This process is repeated all the way to global governance of joint resources such as fresh water, oceans, biodiversity, climate, air quality, forests, etc.

2.1.3 Stakeholder engagement in the context of Good LME Governance

Stakeholder engagement includes a variety of practices to ensure involvement of the public and specific interest groups in public decisions and implementation. It is an essential component of good LME governance by promoting the principles of transparency, inclusivity, accountability, and fairness. It is expected to contribute to effective governance as policies and practices developed with stakeholder input are more likely to be adopted and fulfil their goals.

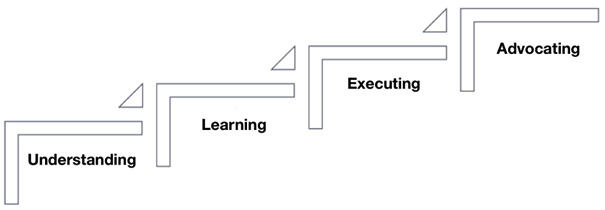

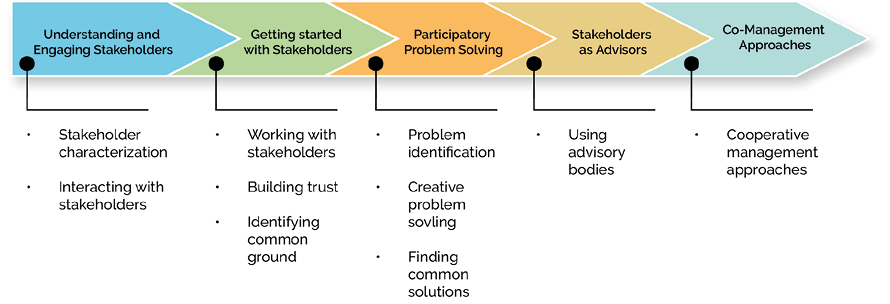

Stakeholder engagement is a process. A ladder of engagement is a framework designed to build engagement (Figure 1). The process works by getting stakeholders to contribute through increasingly important actions that contribute to the realization of the stated goal (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The ladder of engagement (LME Governance Toolkit)

Figure 2: Steps of Traditional Stakeholder Participatory Processes (Walton et al. 2013)

2.2 Stakeholder participation in Large Marine Ecosystem management

LME project’s management includes a number of processes where understanding of stakeholder groups and their interests, as well as their meaningful engagement, are critical for its success. To contribute significantly to building understanding and cooperation between stakeholder groups, the LME planning and management processes should always aim to effectively implement appropriate levels of stakeholder engagement. Ultimately, the trust built through these processes will contribute to achieving goals of an LME project.

The processes for the development of the National Diagnostic Analysis (NDA), TDA and SAP for an LME require deep understanding and identification of the relevant stakeholder groups. In each of these processes, stakeholders should be identified and their interest and thus their influence in relevant features of the LME determined. Understanding stakeholders in this way can be pursued through the Stakeholder Mapping process (summarized presentation starts in section 4.2.1 of this toolkit). It is important to consider stakeholder groups that are relevant to each of the five ecosystem-based five-modules of LMEs approach:

•Governance,

•Socio-economics,

•Productivity,

•Fish and Fisheries, and

•Ecosystem Health & Pollution.

For each module there are stakeholders which have a role in management of its key elements, as well as those who are beneficiaries of ecosystem services, and those who may be contributing to ongoing threats. With this in mind, the stakeholder mapping tool categorizes stakeholders into the following groups (Table 1):

Table 1: Generic stakeholder groups

|

Government |

|

Private |

|

Donors |

|

Civil Society |

|

Local Associations |

|

Academia |

|

International Organizations |

|

Indigenous Peoples |

|

Local Communities |

In developing SAPs and NAPs, additional effort should be made to expand on Stakeholder Mapping to determine how different stakeholder groups will be best engaged in key strategic actions that will be pursued under the SAP at national and subnational levels. This may regularly require consideration of how to engage the different stakeholder groups in each proposed Strategic Action.

►Nesting, subsidiarity, and community-based environmental governance beyond the local scale