4. Regional Ocean Governance

4.1 Scale of governance in LMEs

Governance in LMEs occurs at a variety of scales including the local, national, regional and global level. For “good” ocean governance, coordination is needed between all levels of implementation. Policies and institutions at different spatial scales may sometimes conflict or require alignment. Cultural differences may also need to be addressed at the different spatial scales. For example, indigenous peoples often have different rights and management roles in different countries. Some countries have delegated management or co-management of protected areas to indigenous people, while others provide a more limited role, such as consultation or public comment.

Local

LME governance at the local scale acknowledges the need for community-based management, and the important role indigenous and local communities play in the co-creation of sustainable environmental policy making. Stakeholders have the knowledge and experience to contribute meaningfully to the management of ocean resources within an LME through the TDA process.

National

National level ocean governance occurs within one state and requires coordination between different actors including: the different ministries of the government (as the division of functions and responsibilities for ocean sectors may be among multiple ministries) and stakeholder groups, such as industry or environmental groups. Within national governments, National Intersectoral Committees, as a requirement of GEF IW Projects, can contribute to this coordination.

Regional

At the regional (supra-national) scale, the scope of LME management becomes more complex. The focus is on cooperation among LME countries for management of transboundary issues. The UN Environment Regional Seas Programmes are an example of a platform for cooperation on specific environmental issues for countries sharing seas. The TDA/SAP process provides opportunities for regional level cooperation at the scale of LMEs. The Coral Triangle Initiative is an example of a regional strategy that builds on national-scale implementation of coral conservation actions. Another example are the regional marine protected area networks (e.g. MEDPAN, NAMPAN, RAMPAO and CAMPAN) that link implementation at the site level to institutions and policies at the regional scale.

Global

The United Nations and its agencies are an important forum for ocean governance. The sustainable development goals, UN agency related global conventions, and other governance mechanisms provide important high-level frameworks for guiding the development of environmental policy at national and regional level. There are also several global conventions with independent secretariats that drive global and regional agendas. At the global level NGOs play an important role in agenda setting as well.

4.1.1 National Scale: National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms (NICs)

National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms are bodies that serve to coordinate policies and actions across multiple sectors to advance effective resource management in LMEs. These bodies can be legally or administratively established. Within a range of possible arrangements an effective NIC would:

•Involve stakeholders comprehensively; state actors - government agencies, parastatal bodies, non-state actors - NGOs, CBOs and academia, and private sector - from small to large enterprises;

•Promote an enabling environment that ensures opportunity and support for stakeholder participation and encourages change agents such as individual leaders and champions;

•Have a clear mandate that is at least administrative (politically endorsed) but preferably legal (for legitimacy and accountability) to ensure internal communication among stakeholders and a system for documentation of activities to promote transparency and responsiveness;

•Have an institutionalised mechanism for regular review, evaluation, learning and adaptation (for efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness);

•Serve to integrate sectors and actors involved in marine affairs at the national level;

•Function as a two-way linkage between national and regional government processes;

•Address other functions specific to their scope and mandate, including using marine ecosystem-based approaches, social-ecological system frameworks, risk analysis and resilience or vulnerability concepts.

Some potential NICs may not be well matched to the needs of the LME. Issues of mismatches of scale and scope have impacts on NICs in several ways (See section 4.1.5). Despite the mismatches, NICs have the potential to expand and improve.

4.1.2 Links

►Report on the Survey of National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms

4.1.3 Example: National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanism (NIC) in the South China Sea LME

National intersectoral coordination contributed to project success despite international tensions in the South China Sea LME, providing a model for how NICs can be approached.

The South China Sea LME Project (mainly 2002-2008) was an early LME Project. Given the political tensions among countries in the region particular care was taken with setting up the arrangements for project implementation. There was the need to promote cooperation on environmental issues facing the South China Sea while ensuring that the treatment of these issues had no political implications for the countries, in particular for China’s claim to most of the area.

National Component Committees, technical working groups, and inter-ministry committees were created to ensure representation and coordination between national coordinators, stakeholders, and government officials.

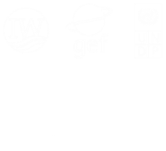

The relations between the national committees and the regional ones are illustrated in Figure 4.1.. The two-tiered structure was designed to provide separation between technical and policy discussions within the Project. The arrangement was determined by the Terminal Evaluation (TE) to have worked well. It was evident that participants in the various committees were clear on their roles vis-à-vis the other committees.

Figure 4.1. Arrangements for the South China Sea Projects showing the relations between national and regional committees (Source: Pernetta and Jiang, 2013)

4.1.4 Links

►Environmental cooperation in the South China Sea: Factors, actors and mechanism.

►The South China Sea Project: a multilateral marine and coastal area management Initiative.

►Managing multi-lateral, intergovernmental projects and programmes: the case of the UNEP/GEF South China Sea project

4.1.5 Example: Connecting National and Regional Level Governance –

National Implementation Committees in the Caribbean+ LME

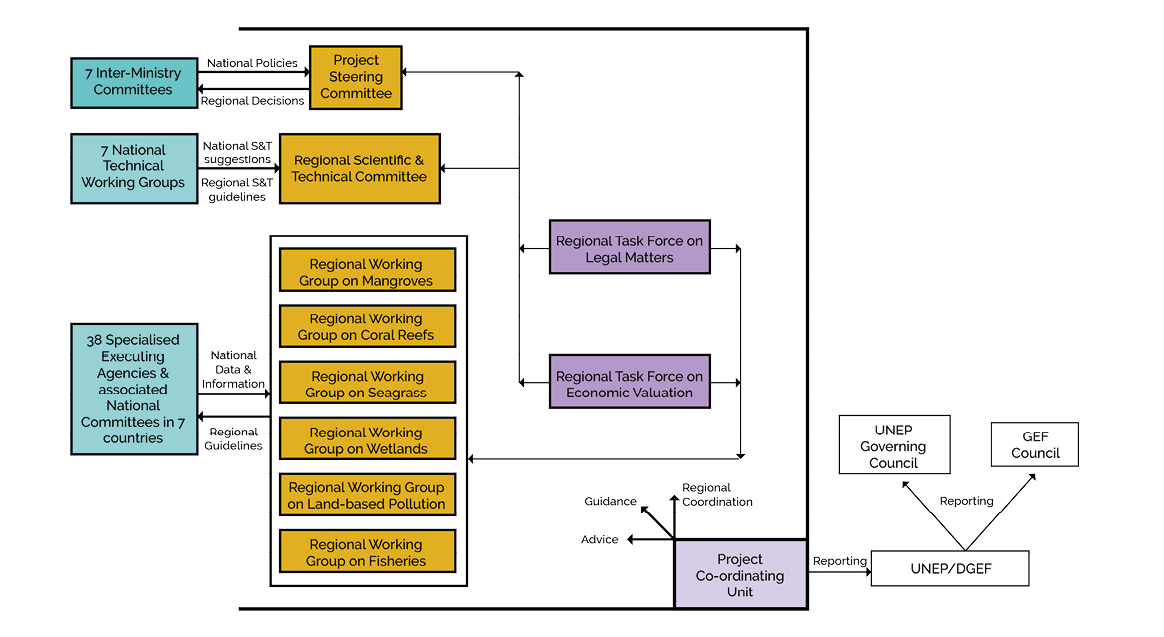

Effective transboundary governance requires that national and regional levels be linked by transparent, accountable processes, such as that developed in the Caribbean+ LME (Figure 4.2). A survey across all CLME+ countries was conducted to determine the extent to which current practices followed the concepts in the model process. Countries rarely undertook the full process, with Stages 3 and 8 often omitted, with irregular feedback to stakeholders. Ad hoc informal committees met infrequently. Multi-stakeholder arrangements were recognized as important, but seldom implemented. Selecting an inappropriate representative was common and led to ineffective representation, together with inadequate representation of civil society /private sector. Weak NGOs and Community –Based Organizations (CBO) made communication challenging.

Figure 4.2 Model transboundary governance

Lessons learned in this example were:

•Structured processes are important for achieving effective multilevel governance and institutionalizing these processes ;

•Sectoral/fragmented approaches to regional processes are common, but reduce effectiveness ; and

•Informal relationships and social networks are key for communication.

4.1.6 Links

►Ocean governance in the Wider Caribbean Region: Communication and coordination mechanisms by which states interact with regional organisations and projects.

4.1.7 Tool: Analyzing Gaps in Institutions at the Regional Scale

This tool provides guidance to planners and managers in examining the extent to which the existing suite of governance arrangements in an LME or region covers the issues and geographical areas in need of governance with complete policy processes. Steps in the process are as follows :

•Identify the organizations involved in governance of coastal and marine issues in the region ;

•Review the scope of each organisation in terms of issues (e.g. various fisheries, types of pollution and habitat degradation), and geographical areas covered is reviewed using the establishing agreements, by-laws and information provided through their websites. In addition the review examines which stages of the policy cycle (Figure 1) the organisations have a mandate to engage in;

•Develop matrices to summarize findings and reveal gaps and overlaps in processes and mandates; and

•Facilitate a discussion among regional organisations of their respective roles in regional ocean governance and what can be done to fill gaps or minimize overlaps.

This analysis can also be carried out on the basis of the actual work of the organisations to provide a comparison of their mandated and actual activities. The application of this approach in the Wider Caribbean Region can be found in Mahon et al. (2013). See figure 2.1.

This process was applied in the Wider Caribbean Region, and revealed a number of gaps and overlaps in terms of both mandate and geographical coverage. These were considered in developing the Regional Ocean Governance Framework and CLME+ SAP

4.1.8 Links

►CLME+ Strategic Action Programme(SAP).

►Governance arrangements for marine ecosystems of the Wider Caribbean Region

►Assessing and facilitating emerging regional ocean governance arrangements in the Wider Caribbean Region

4.1.9 Example: HOPE: Healthy Oceans, People and Economies—Ocean and Coastal Governance in the Seas of East Asia

The East Asian Seas (EAS) is a region covering 14 countries and 6 LMEs: the East China Sea, Yellow Sea, South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand, Sulu-Celebes Sea and the Indonesian Seas. To address the alarming degradation of their seas, coasts and estuaries, the collective response of these countries’ governments was the crafting and adoption in 2003 of a regional marine strategy known as the Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-SEA). The countries were able to accomplish this by utilizing the platforms of the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA).

PEMSEA is an international organization specializing in integrated coastal and ocean governance and acts as a regional mechanism in active collaboration and partnerships with its 11 country and 21 non-country partners: a Partnership Model. This was a different track from that taken by most other regions, which were able to forge legally binding conventions and agreements. The collaborative networks or partnerships established by PEMSEA at the local, sub-regional, and regional levels brought about consensus among the partners of the shared vision, mission, objectives and action programs in the implementation of SDS-SEA.

The region’s SDS-SEA has been contributing to achieving the goals of key international agreements and action plans, including Chapter 17 of Agenda 21, The UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). With the recent adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the SDS-SEA had been re-framed to implement HOPE: Healthy Oceans, People and Economies

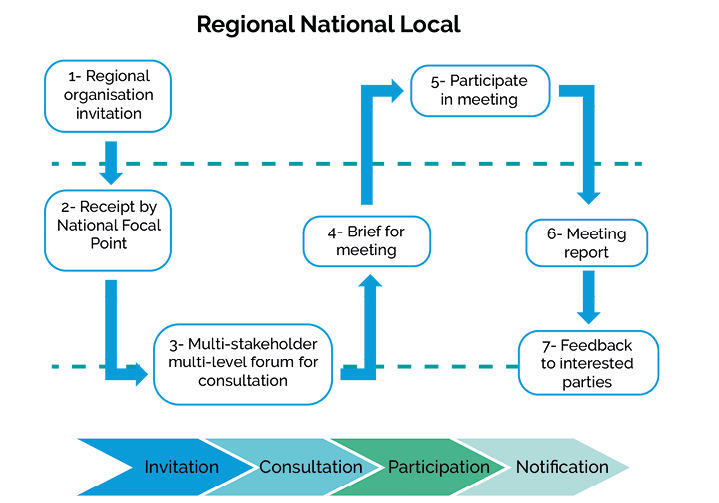

At the local level, the principal vehicle used by PEMSEA for addressing the sustainable development objectives and targets identified in SDS-SEA is Integrated Coastal Management (ICM). From 1994 to 2014, PEMSEA established ICM sites in 26 locations, demonstrating the value of ICM and building capacity for expansion to other locations. Building on the experience gained at these sites, PEMSEA’s partner countries began expanding in 2015 to 31 additional sites around the region, in collaboration with local governments (see Figure 4.3). PEMSEA developed the State of the Coasts (SOC) reporting system to operationalize monitoring and evaluation (M&E), which was tested in several of its ICM sites. The SOC evaluates 35 core indicators covering the governance elements and sustainable development aspects of each local government. The SOC is developed through a stage-wise, multi-sectoral and consultative process.

Figure 4.3: ICM replication and scaling up in the EAS region