5. Effective Governance – Achieving Our Goals

5.1 Effective governance

While good governance is the “what” of what we aim to achieve, effective governance is the “how” of accomplishing this, including implementation, compliance and enforcement. Compliance and enforcement are key components of effective LME governance. However, these actions are usually taken at the national scale, and benefit from trans-boundary cooperation to address large LME scales. This can be accomplished through measures such as joint management agreements that include provisions on cooperative compliance and enforcement. New “big data” tools, such as monitoring global fishing via satellite, offers new opportunities for collaborative enforcement.

5.1.1 Links

5.1.2 Examples: Compliance through communication

5.1.2.1 London Protocol

The 1996 London Protocol (1996 Protocol to the Convention On the Prevention of Marine Pollution By Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972) has a set of Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms, pursuant to Article 11, which includes the establishment of a subsidiary body - the Compliance Group - that meets in parallel to the Meeting of Contracting Parties and provides advice to the Parties on compliance matters. The Compliance Group was established in order to assess and promote compliance with the London Protocol, with a view to allowing for the full and open exchange of information, in a constructive manner. For further information see:

►http://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/lclp/compliance/pages/default.aspx

5.1.2.2 Barcelona Convention

IIn order to support and assist Contracting Parties to meet their obligations under the Barcelona Convention (BC) and its related Protocols, the Compliance Committee of the Barcelona Convention, as a subsidiary body, has been established with the aim to facilitate, promote, monitor and secure compliance with the BC legal framework. The Committee considers cases submitted by a Contracting Party, regarding its effective or potential situation of non-compliance with obligations, or regarding a situation of non-compliance on the part of another Party. The Compliance Committee must report its findings to the Contracting Parties, but it may not apply sanctions. Instead, it may take steps to facilitate compliance, such as giving advice, requesting an action plan to bring the Party into compliance or making recommendations to meetings of the Contracting Parties on cases of noncompliance. For further information see Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms under the Barcelona Convention and its Protocols

5.2 Assessing governance

The comparative analysis of governance assessment among International Water (IW) categories is most easily approached using a common framework for discussing governance assessment. This framework facilitates the development of appropriate indicators for its various parts. There are several frameworks that can be drawn upon, for example, the Institutional Analysis Framework, Interactive Governance Approach, the International Lake Ecosystems Committee (ILEC) six pillars approach, Governance Framework, the TWAP Open Oceans/LME modified DPSIR, and the expanded GEF IW indicator framework developed for the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Project. These frameworks range from highly conceptual to operational. They are not mutually exclusive or independent and have many common elements.

In the case of Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP) there is the need to have a practical framework that can be used to operationalize governance assessment. Some desirable characteristics of such a framework include:

•Easy to understand, so that it is clear what the selected indicators cover and what they do not;

•Comprehensive, so that the indicators cover all the aspect of governance that should be addressed;

•Well-grounded in governance thinking and concepts; and

•Connected with actions that can be taken to improve governance.

For the comparative analysis of governance assessment in the TWAP, the GEF IW indicator framework was considered to be the most appropriate. It appears to meet the criteria listed above.

(Adapted from the Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP) Crosscutting Governance Working Group Report).

5.2.1 Tool: The GEF Transboundary waters assessment framework

The assessment of governance arrangements and their effectiveness is complex and can be facilitated by a framework of appropriate indicators. The GEF IW indicator framework provides thematic assessment approach appropriate for monitoring interventions and may lead to proposals for corrective measures.

To facilitate evaluation, one perspective is to break what governance is expected to achieve into three components:

•”Outputs”, which are the arrangements that are put in place to achieve governance;The second is ‘outcomes’ which represents changes in the behaviour of people that are the target of the arrangement.

•”Outcomes”, which represent changes in the behaviour of people that are the target of the arrangement; and

•”Impacts”, which represent changes in the state of the system that is the target of the arrangement.

Other assessment frameworks allow for considerations to be made regarding both interventions and the assumptions underlying those actions with focus on the entire management cycle and ensuring that mechanisms are in place within the governance architecture to allow for adaptation, should the desired outcomes not be achieved.

For example, four orders of outcomes can be considered (Olsen, 2003):

1Enabling conditions

2Changes in behaviour

3Improvements in the system

4Sustainability achieved

Similarly, considers four categories of indicators needed to assess governance of coastal and ocean systems could also be considered:

1Inputs;

2Processes;

3Outputs; and

4Outcomes.

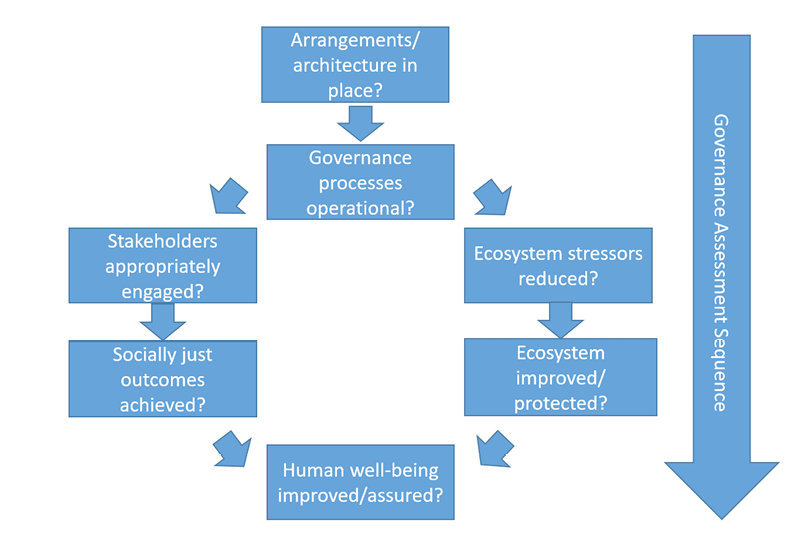

Coverage across different components of the management cycle is needed in order to, identify which elements of management to adapt. These components can be assessed separately with appropriate indicators. They should also be assessed in sequence, as it is likely that there will be time lags in changes in them. This perspective is consistent with the formulation of the GEF IW programme approach to evaluation of its projects and interventions, which has been based on the following categories of indicators: (1) process indicators (2) stress reduction indicators and (3) environmental status indicators (4) governance architecture (5) stakeholder engagement, (6) social justice and (7) human well-being. The latter three are in tandem with those for environment (Figure 5.1). Governance architecture, is included because assessment of the indicators will be dependent upon the institutional structure in place to facilitate decision- making, planning, and implementation.

The view that an appropriate governance structure is a necessary but insufficient condition for successfully achieving improved human well-being, led Mahon et al. (2013) to call for the assessment of governance architecture to precede the assessment of governance process. This distinction is considered to be particularly important in the case of multilevel nesting typical of international environmental governance systems. Governance architecture is “…the entire interlocking web of widely shared principles institutions and practices that shape decisions by stakeholders at all levels in this field”. (Biermann and Pattberg, 2012).

Figure 5.1.1 The GEF IW indicator framework (adapted from Mahon 2013).

The GEF IW indicator framework provides for the full set of indicators needed for a comprehensive governance assessment (Figure 5.1). The seven indicator categories cover the two major aspects of such an assessment:

•a) Determining if governance arrangements and processes have been set up in a way that is consistent with accepted institutional norms and practices (architecture, process, engagement) - namely whether ‘good governance’ is in place;

•b) Determining if the governance practices have achieved what they were established to do (ecosystem pressure, ecosystem state, social justice, human well-being) – namely whether there has been ‘effective governance’.

Ultimately, ‘good governance’ characteristics might be expected to produce better governance results. However, the state of governance research is such that it is not possible to be definitive about the relationship between ‘good governance’ characteristics and governance effectiveness. Nonetheless, ‘good governance’ characteristics are often cited as being desirable attributes of governance architecture and processes in their own right (Lemos and Agrawal 2006, Lockwood et al. 2010).

The indicators categories shown in Figure 5.1 form an assessment sequence. The indicators in the earlier (upper) categories will be verifiable sooner after implementation than the later (lower) ones. Ecosystems may take decades to respond to reduced pressures; and changes in human well-being is only likely to occur after ecosystem and social justice outcomes have occurred. A further complication is that as one moves down the sequence it will be more difficult to demonstrate cause and effect between interventions, outcomes and impacts. It will often be clear that a process outcome (plan or regulation) has led to a pressure reduction. However, tracking the effects of a pressure reduction on system state or of system state on well-being may be more difficult due to confounding factors that are external to the intervention that is being assessed.

5.2.2 Using the indicator framework

An indicator shows if there has been some changes in a selected attribute of the system being monitored. The indicator should have directionality so that it shows whether the attribute is improving or deteriorating. Ideally, an indicator should have target or threshold values which are to be aimed for or to be avoided. However, when the state of an attribute is clearly undesirable, identifying the direction of change needed for improvement may be enough to guide governance action until targets can be determined. Even when the same indicators are used in different IW systems, the target levels must be situation specific and may differ among instances.

Indicators can be used as a monitoring tool to provide the feedback necessary to measure progress toward stated management goals and objectives. In contrast, indicators used for evaluation provide insight into the effectiveness of the stated goals and objectives. These assessments are essential to adaptive learning within complex coastal systems as the findings may reveal information leading to a rerouting, rereading and reinterpretation of the stated goals and objectives.

In order to ensure that there is comprehensive assessment of both good governance and effective governance within a transboundary water system, indicators should be developed and monitored in each of the seven categories (Figure 5.1) for each issue identified as being of concern in that system. Adequate coverage of an indicator category may require more than one indicator. Consequently, in developing a governance assessment or monitoring programme, it may be necessary to consider subcategories of the indicator for each category.

5.2.3 Links

►Governance of Protected Areas: From understanding to action

5.3 Communicating with policy-makers

Policy-makers are the people whose decisions and opinions have the ability to directly influence law, and binding regulations. These may include: elected officials, parliamentarians, ministers, parliamentary committees, civil servants, scientific or political advisers and members of regional assemblies and local authorities.

There is a considerable body of research literature on the use of science in decision-making. Frequently, disconnect between suppliers and users of technical information is identified. There are many reasons for this, but the primary one is that the suppliers of information do not invest enough time (oftentimes they are not motivated to) in understanding the demand and engaging with the processes that transforms this information to decision-makers. Moreover, technical programs and projects often develop a considerable amount of information and scientific knowledge that is not adequately used in developing policy and making decisions.

When presenting evidence and messages aimed at influencing policy it is important to consider:

1Policy-makers ability to interpret evidence. (Do they have the necessary data analysis skills?)

2Organizational and structural barriers to uptake of evidence. (Is the timeframe for decision making aligned with the delivery of the evidence or project outcome); and

3Policy-makers may be influenced by quantitative vs. qualitative evidence in unexpected ways. (Will the hard data or anecdotal evidence be more compelling?).

There are numerous avenues available to influence policy with the best available scientific information. These range from getting the ear of the Minister or his technical adviser at a cocktail party, or in the corridors of a meeting or conference, to taking the information through a well-structured and established science policy process. From a good governance perspective, the latter mechanism is preferable. If well structured, it should provide for transparency, inclusivity, accountability, and adaptiveness (among other desirable characteristics). Economic information is particularly important to decision-makers (see information on the Economic Tool Kit in Section 2.4.1).

A complete policy process would involve the capacity to:

1generate or access data and information;

2analyse data, information and advice;

3take decisions;

4implement what has been decided upon and

5review the effectiveness of what was implemented as a basis for future advice.

Ideally, decisions taken will be binding. In LME or transboundary context, the decision-making part of the policy process must be well connected with the countries comprising the LME. In order to achieve decision-making that is binding upon the countries, it is desirable that the policy processes be linked with or embedded within regional intergovernmental organisations that have full membership of the countries within the LME. The regions will also often have indigenous multipurpose organisations, usually oriented towards economic integration, which Regional Sea/LME projects could engage with to acquire support, consult and legitimize processes and decisions.

5.3.1 Links

►British Ecological Society top 10 tips for engaging with policy-makers

►Example of a publication tailored for policy-makers:Large Marine Ecosystems status and trends summary for policy-makers

5.4 Tool: Soft Law – policy drivers

Soft law (written soft rules) and informal governance (unwritten rules), while non-binding, can be of greater influence on human behaviour than formal governance mechanisms. Decision-making at an individual and community level commonly reflect local values and perceptions that can shape attitudes and actions. When these actions build social capital then group behaviour can become powerful in determining locally agreed rules, for example, compliance with marine protected area regulations. Social capital can simply be described as social relations that collectively produce benefits greater than the sum of the parts. In coastal communities, especially those that are remote or isolated from the main population or are located far from those enforcing regulations, social norms will play a major role in determining likelihood of rule-breaking or compliance with both formal (e.g., fishing restrictions in marine protected areas) and informal (agreed shared benefits from access to marine resources) governance mechanisms on a day-to-day basis. Thus when considering the relationship between governance effectiveness and marine management efficacy, understanding the role of informal governance and soft law is critical to choosing measures more likely to be supported.

The role of soft law in linking marine regulatory commitments with what is enforceable locally has not been given the attention needed. While most marine policy describes itself as “science-based,” social science is frequently not incorporated into policy and legislation. To illustrate, ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, advice for fisheries policy is based on annual fish stock assessments, based on ecosystem and fisheries data, stock distribution, assessment model, forecast method and reference points.

ICES, like many organisations and governments worldwide are increasingly recognizing the value of using interdisciplinary teams and methods to consider the human dimension in marine governance. Therefore, more effort is being placed on the integration of social and economic sciences into marine policy making. Socio-political considerations should cover the whole range of stakeholders and their type of involvement in the establishment and operation of managing marine resources. Specialized training is needed on interdisciplinary science methods for marine policy advice. A lack of understanding about linkages between decision-making by different actors and stakeholders and between different levels at which decisions are made (local industry, national jurisdiction authority and international conventions/treaties) can lead to fragmented and weak governance systems (Krause and Stead, 2017).

One way to visualize these linkages is to create a governance framework to facilitate decision-making. Governance frameworks that integrate social, economic and environmental information (e.g., see Krause et al., 2015) can help define responsibilities and duties, so that different demands and practices of the involved parties can be considered. To illustrate, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) – developed in 1991 and adopted in 1995 - is an example of a voluntary framework. It was developed to help focus national and international efforts in establishing principles and standards applicable to the sustainable exploitation of aquatic living resources in harmony with the environment. The principles of the FAO Code, include the nutritional, economic, social, environmental and cultural importance of fisheries and interests of those associated with this sector. It also considers the biological characteristics of resources and their environment with impacts on consumers and other users. Although the Code is voluntary, parts of it are based on relevant rules of international law, including the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea. This code helps individual States develop their own policies and governance to develop responsible fisheries management, and to provide guidance on the formulation and implementation of international agreements. The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries inspired other sectors such as the European Aquaculture Sector to establish its own common framework to promote self-regulation, another type of soft law. Complimentary guidelines to the CCRF is the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries.

Recognising that policy drivers will change over time and inform marine management actions for the future, complexity in decision-making is likely to increase where there are demands from multiple users of the same coastal and ocean space. Ideally, expected changes to the social, economic and marine ecosystems should be considered in advance of policy formulation and management developments so that governance systems can be tailored to the context-specific needs of different locations.

5.4.1 Links

►The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

►Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries

►European Aquaculture Sector – FEAP Code of Conduct

5.5 Marine Protected Areas

Marine Protected Areas (MPA), Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) and Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) are ocean governance tools or practices that can be applied at a range of spatial scales from local to regional. They are also connected. ICZM focuses on the land/sea interface of the coastal zone, addressing such issues as watershed management, coastal access, coastal industries, land use planning, and coastal habitat conservation and management. MSP takes a similarly comprehensive look at spatial planning in the ocean environment. Both ICZM and MSP may identify the need for MPAs as tools to protect important habitats, features or species.

MPAs refer to areas in the coastal and marine environment that have been designated for long-term protection. There are many types of MPAs, ranging from marine reserves, which prohibit all extractive uses (e.g. fishing, mining, oil and gas production) to multiple use MPAs that allow a wide range of uses that are compatible with long-term conservation. The Convention on Biological Diversity and the UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 both call for countries to conserve 10% of marine and coastal waters in representative, effective MPA networks. MPA networks can multiply the conservation benefits by sizing and spacing individual MPAs to allow for the export (or “spillover”) of marine larvae and juvenile fish outside MPA boundaries, serving as “stepping stones” of similar protected habitats as species ranges may shift with climate change, and serving as “insurance policies” in case of catastrophic impacts to a single MPA, such as an oil spill or ship grounding.

Effective governance of an MPA is necessary to achieve biodiversity conservation objectives and social economic development.

5.5.1 Tool: Enabling effective and equitable Marine Protected Areas: guidance on combining governance approaches.

This introductory guide provides insightful and evidence-based advice on how to approach the governance of marine protected areas (MPAs) to promote conservation, sustainable use and the sharing of marine resources. It includes practical guidance on how to effectively approach marine protected area governance as well as tackling the difficulty in translating and implementing decisions made at the international level to a local context. Effective governance in MPAs is important to achieve conservation and ecosystem services goals.

5.5.2 Links

Enabling effective and equitable Marine Protected Areas: guidance on combining governance approaches

UN Environment/Blue Solutions (forthcoming publication – link to be inserted) www.mpag.info

5.5.3 Example: Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas

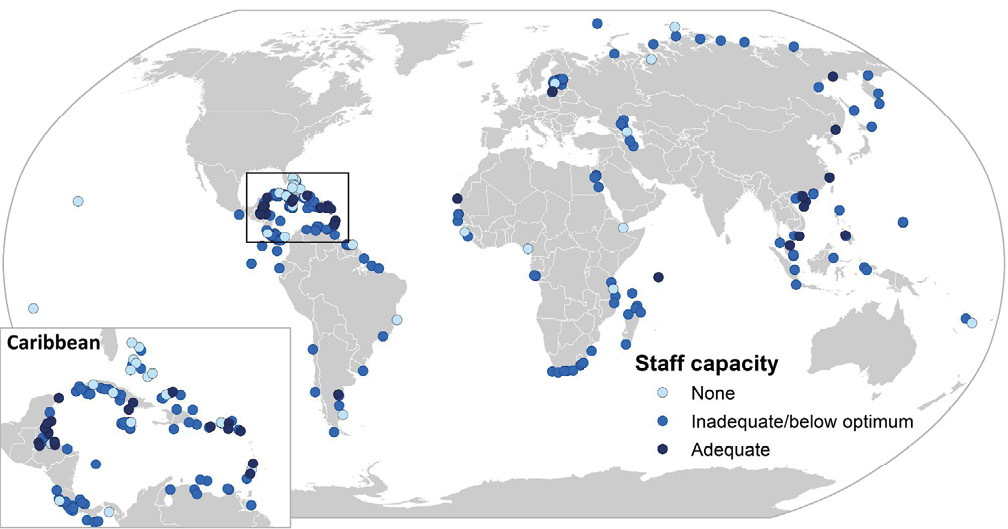

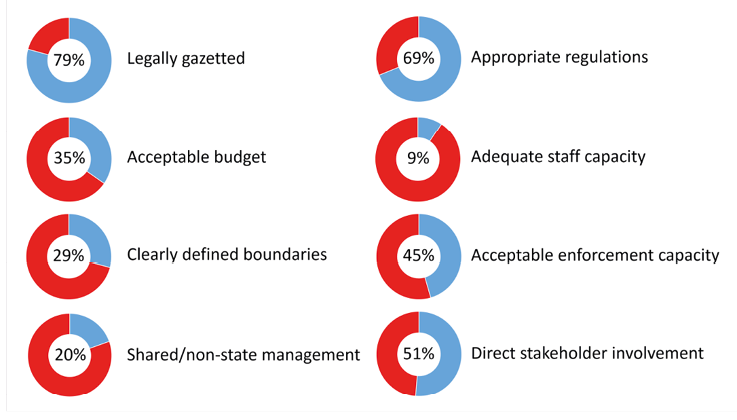

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have become an important tool to protect marine biodiversity. A recent global study examined MPA performance and how MPA management influences ecological outcomes and found that MPA management processes remain very weak. Only 51 percent of MPAs said that local stakeholders had direct involvement in decision-making, and a mere 9 percent of MPAs reported adequate staff to carry out critical management activities (Figure 5.2).

Although 71 percent MPAs had positive impacts on fish populations these ecological impacts were highly variable. Of the ten management indicators, staff and budget capacity were the most important factors in explaining the variation in fish population impacts in 62 MPAs where both management and ecological data were present (Figure 5.3). The strong correlation between capacity and other key management activities (e.g. enforcement, monitoring), indicate that capacity shortfalls are likely to be limiting the potential of many MPAs around the globe from achieving their conservation and management objectives.

While the global community focuses on expanding the current MPA network, these results emphasize the importance of meeting capacity needs in current and future MPAs to ensure the effective conservation of marine ecosystems.

5.5.4 Links

►Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally

Figure 5.2 Only 9% of MPAs reported having adequate staff capacity to carry out critical management activities.

Map from Gill et al (2017).

Figure 5.3 Percent of MPAs exceeding (blue) or falling below (red) threshold values for indicators of effective and equitable management processes.

5.6 Example: Identifying Good Practices in National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms (NICs) in the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf (CLME+) LMEs

The National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms (NICs) across the CLME+ region (CLME and NBS LMEs) provide an example of best practice. The Inter-ministerial Commission of Sea Resource (CIRM; with a secretariat and four working groups), the Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC; responsible for the creation of Fishery Management Plans for fishery resources in the US Caribbean EEZ of PR and the USVI), the Colombian Ocean Commission (CCO) (evolved from its naval focus on oceanography to a broader focus on sustainable development of oceans) and the OECS Ocean Governance Committees (OGC) are devoted to sustainable ocean governance in the region. In addition to member states participation of a large number of NGOs, civil society and private actors are involved in ocean and coastal zone governance in a very inclusive, participatory, consultative and coordinating way in the region. This example illustrates that adaptation, as well as coordination of a diverse array of initiatives and developmental directions and sufficient institutional arrangements are important to achieve a good regional marine environmental future from short to medium-term projects.

5.6.1 Links

►Report on the Survey of National Intersectoral Coordination Mechanisms.