3. Policy and Legal Frameworks

3.1 International legal framework and institutions

Ocean governance is the public and private interactions undertaken to address challenges and create opportunities within society. Governance thus includes the development and application of the principles, rules, norms, and enabling institutions that guide public and private interactions. Institutional arrangements within LMEs are the formal and informal measures and cooperative mechanisms that influence collective and individual action at all scales from regional to local.

The 1982 Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) provides the international legal framework for the balance of coastal State and flag State jurisdiction of nations over activities at sea. The LOSC recognizes the coastal States jurisdictional rights, authority, and responsibilities over certain maritime zones (e.g., EEZ), including how their authority is balanced in regard to the rights of other nations (vessels and persons) within the maritime zones.

The maritime zones of coastal States (Figure 3.1) include the 12 nm territorial sea, the 24 nm contiguous zone extends, and the 200 nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The continental shelf is land and subsoil under the EEZ. The normal baseline for measuring or delimitating these zones is from the low water coastal tide line as depicted on official charts. The continental shelf of a nation may extend beyond 200 nm and there are specific rules about its delimitation. Coastal States have jurisdiction and authority over foreign nation’s right to lay cable and pipelines on the coastal States continental shelf, and authority for the protection, conservation, development and use of marine resources.

The areas beyond the 200 nm EEZ and the extended continental shelf are called the “areas beyond national jurisdiction” (ABNJ; note that coastal countries have rights and exclusive jurisdiction over the seabed in the extended continental shelf, but do not have exclusive jurisdiction over the water column in that zone.) The UN is currently considering governance mechanisms for managing biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. As a science-based ecosystem approach, LME projects may be able to provide science and management expertise to assist in the management of ABNJ.

Figue 3.1 Maritime zones (Source: http://continentalshelf.gov/media/ECSposterDec2010.pdf )

Intergovernmental programmes and organizations are an important aspect of governance as they represent consensus among member states. International treaties/conventions come into force when lawful representatives of several states go through a ratification process, providing the programmes/organizations with international legal personality.

The LME concept provides knowledge and tools for enabling the ecosystem-based management of human activities. This collaborative approach to management aims at advancing transnational ocean governance consistent with international law and institutions.

The following specific themes are covered by major international legal frameworks that exist and are actively involved in ocean governance on a global or regional scale:

•LOSC recognized rights and responsibilities of nations (coastal States and flag States) with respect to their use and management of activities in the ocean;

•Maritime safety / shipping regulations / marine pollution: The International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO’s primary purpose is to develop and maintain a comprehensive regulatory framework for shipping and its remit today includes safety, environmental concerns, legal matters, technical co-operation, maritime security and the efficiency of shipping;

•Environmental protection / management: UN Environment Regional Seas Programme. More than 140 countries have joined 18 Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans for the sustainable management and use of the marine and coastal environment. In most cases, the Action Plan is underpinned by a strong legal framework in the form of a regional Convention and associated Protocols on specific problems (E.g. the Convention on Migratory Species, Polar Bear Convention, etc.);

•Biological diversity: The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Convention’s main goal is conservation of biological diversity. The agreement covers all ecosystems, species, and genetic resources. It links traditional conservation efforts to the economic goal of using biological resources sustainably. Importantly, the Convention is legally binding and nations that join it are obliged to implement its provisions therefore regional programmes like LMEs need to take these provisions into consideration;

•Fisheries/aquaculture: Regional Fisheries / Aquaculture Management / Advisory Organizations / Regional Sea Organizations - international organisations formed by countries with fishing / aquaculture interests in an area. These bodies, where existing for a specific sea basin, are considered to be key components of a working system for global ocean management. Cooperation between LMEs and Regional Management / Advisory bodies is stimulated and encouraged by the FAO. While most of the LME mechanisms being driven primarily by environmental concerns, RFBs and national fisheries authorities have not always been actively involved in LME discussions and decisions, despite fisheries often being the main issue at stake.

These international legal organizations are supported by international science organizations / programs that provide evidence and formulate recommendations for policy making.

International Science Organizations / Programs: e.g. IOC of UNESCO / IMBER / ICES / PICES / WAS. These entities publish scientific results, are sponsors of scientific meetings, and develop marine assessments and in some cases holistic ecosystem overviews. These are state of ecosystem reports (integrated ecosystem assessments) comprising quantitative evaluations and synthesis of information on physical, chemical, ecological, and human processes. They provide scientific understanding to deliver advice on societal trade-offs between different policy options therefore are a valuable source of evidence-based advice for regional programmes like the LMEs. Similarly, the Large Marine Ecosystems perform TDAs for SAPs within their territorial boundaries. Another common activity is data collection (mostly by national institutes and projects): international organizations harmonize data collection activities mechanisms and management e.g. the ICES Data Centre or IODE for IOC-UNESCO.

International science organizations also provide knowledge to the LME/regional managerial authorities that support:

•banning harmful fisheries subsidies;

•fighting illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing;

•fighting marine debris;

•promoting maritime spatial planning at macro-regional and global levels; and

•promoting educational and technological development.

The above mentioned components of maritime governance at various regional scales provide tools and solutions for developing sustainable approaches to ocean management. Input provided by existing organizations contributes to the challenge of linking and coordinating national, regional and global targets and goals. Together with regional developments at LME level, these need to be aligned with goals, targets, and indicators approved at global level (e.g. SDG targets, the Aichi Targets).

Cooperation within international organizations also provides coordination services and a forum to share experiences / lessons learned / best practices across methodologies to help countries realize global targets and evaluate progress through indicators. This can also help to operationalize goals on a national level, as countries oftentimes have their own nation-specific targets.

Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP) conducted indicator-based assessments for transboundarywater systems including Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) and Open Oceans. These included assessment of governance arrangements and overall architecture for transboundary systems. The TWAP LME report describes which agreements pertain to which LMEs. The annex includes a governance analysis for each of 50 transboundary LMEs, showing how they relate spatially and in terms of engagement to regional agreements that cover all or any part of the LME.

3.1.1 Links

►Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP) Assessment of Governance Arrangements for the Ocean: Volume 1- Large Marine Ecosystems

3.1.2 Examples of international agreements guiding ocean governance

The TWAP found over 140 global/regional agreements relevant for transboundary LMEs. The Table 3.1 provides a short list of examples of international agreements guiding ocean governance.

Table 3.1: Examples of international agreements

|

Title of agreement |

Summary description |

|

Hard Law |

|

|

Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) |

The 1982 Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) provides the international legal framework for the balance of coastal State and flag State jurisdiction of nations over activities at sea. http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm |

|

Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (1995). |

The Agreement contains general principles of stock management and obliges Coastal States to utilize the principles by adopting measures to ensure the long term sustainability of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks and promoting the objective of their optimum utilisation. It incorporates the precautionary approach and the ecosystem approach to the conservation, management, and exploitation of fish stocks in waters under national jurisdiction and in the high seas. http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_fish_stocks.htm |

|

Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (1972 - The London Convention) London Protocol |

One of the first global conventions to protect the marine environment from human activities and has been in force since 1975. Its objective is to promote the effective control of all sources of marine pollution and to take all practicable steps to prevent pollution of the sea by dumping of wastes and other matter. Currently, 87 States are Parties to this Convention. In 1996, the ”London Protocol” was agreed to further modernize the Convention and, eventually, replace it. Under the Protocol all dumping is prohibited, except for possibly acceptable wastes on the so-called ”reverse list”. The Protocol entered into force on 24 March 2006 and there are currently 48 Parties to the Protocol. http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/LCLP/Pages/default.aspx |

|

International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution Casualties (1969) |

Affirms the right of a coastal State to take such measures on the high seas as may be necessary to prevent, mitigate or eliminate danger to its coastline or related interests from pollution by oil or the threat thereof, following upon a maritime casualty. The coastal State is, however, empowered to take only such action as is necessary, and after due consultations with appropriate interests including, in particular, the flag State or States of the ship or ships involved, the owners of the ships or cargoes in question and, where circumstances permit, independent experts appointed for this purpose |

|

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto (1973; MARPOL 73/78) |

The main international convention covering prevention of pollution of the marine environment by ships from operational or accidental causes; includes regulations aimed at preventing and minimizing pollution from ships - both accidental pollution and that from routine operations; Special Areas with strict controls on operational discharges are included in most Annexes |

|

International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Cooperation (1990 - OPRC) |

Global framework for international co-operation in combating major incidents or threats of marine pollution; parties are required to establish measures for dealing with pollution incidents, either nationally or in co-operation with other countries; ships are required to carry a shipboard oil pollution emergency plan; parties must require offshore units to have oil pollution emergency plans to respond promptly and effectively to oil pollution incidents; incidents of pollution must be reported to coastal authorities; establishment of stockpiles for oil spill combating equipment, the holding of oil spill combating exercises and the development of detailed plans for dealing with pollution incidents; parties are required to help others in the event of a pollution emergency, with promise of reimbursement for any assistance provided |

|

Protocol on Preparedness, Response and Cooperation to Pollution Incidents by Hazardous and Noxious Substances (2000 - HNS Protocol): |

Aims to establish national systems for preparedness and response and to provide a global framework for international co-operation in combating major incidents or threats of marine pollution; ensures that ships carrying hazardous and noxious substances are covered by preparedness and response regimes similar to those already in existence for oil incidents |

|

International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (1946) |

The founding document for the International Whaling Commission; sets out goals for catch limits of commercial and aboriginal subsistence whaling |

|

Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar) |

Considers the fundamental ecological functions of wetlands as regulators of water régimes and as habitats supporting a characteristic flora and fauna, especially waterfowl; addresses the fact that wetlands constitute a resource of great economic, cultural, scientific and recreational value, the loss would be irreparable; works to stem the progressive encroachment on and loss of wetlands now and in the future; waterfowl in their seasonal migrations should be regarded as an international resource; conservation of wetlands and their flora and fauna can be ensured by combining far-sighted national policies with co-ordinated international action; http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15398&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html |

|

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora: |

Recognizes that wild fauna and flora in their many beautiful and varied forms are an irreplaceable part of the natural systems of the earth and must be protected for their aesthetic, scientific, cultural, recreational and economic points of view; States are and should be the best protectors of their own wild fauna and flora; international cooperation is required to protect certain species of wild fauna and flora from over-exploitation of international trade |

|

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) |

An international, legally-binding treaty with three main goals designed to encourage action and a sustainable future: conservation of biodiversity, sustainable use of biodiversity, and fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources http://www.un.org/en/events/biodiversityday/convention.shtml Cartegena Protocol on Biosafety (1997): an international agreement that aims to ensure the safe handling, transport and use of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology that may have adverse effects on biological diversity, also taking into account risks to human health CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (2011-2020) Aichi Biodiversity Targets (2010): provides an overarching framework on biodiversity, not only for the biodiversity-related conventions, but for the entire United Nations system and all other partners engaged in biodiversity management and policy development Marine Protected Areas comprise 10% of coastal marine environment (Target 11): By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes |

|

Safety of Life at Sea (1974 - SOLAS) |

The first treaty to address safety and navigation |

|

Soft Law |

|

|

Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm Declaration) of 1972 |

In order to achieve a more rational management of resources and thus to improve the environment, States should adopt an integrated and coordinated approach to their development planning so as to ensure that development is compatible with the need to protect and improve environment for the benefit of their population. |

|

United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992 - Earth Summit) |

Sought to help Governments rethink economic development and find ways to halt the destruction of irreplaceable natural resources and pollution of the planet; Governments recognized the need to redirect international and national plans and policies to ensure that all economic decisions fully took into account any environmental impact; examined the relationship between human rights, population, social development, women and human settlements — and the need for environmentally sustainable development. |

|

Rio Declaration |

Defines the rights of the people to be involved in the development of their economies, and the responsibilities of human beings to safeguard the common environment. The declaration builds upon the basic ideas concerning the attitudes of individuals and nations towards the environment and development, first identified at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (1972) http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-1annex1.htm |

|

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) |

This code helps individual States develop their own policies and governance to develop responsible fisheries management, and to provide guidance on the formulation and implementation of international agreements. |

3.1.3 Practical recommendations:

Based on the above, the following practical recommenadtions for LME context could be proposed :

•Identifying need for measures to address issues in a particular LME from a particular source is important and part of the TDA (e.g., consider Special Area Recognition under authority from IMO in regard to pollution from international shipping);

•Bypassing existing regional ocean governance mechanisms in place should be avoided;

•Collaborative ways to better support, monitor and align reporting on progress in ocean governance should be pursued;

•Formal, structured information exchange channels should be utilized; and

•Dialogue at different levels is important and communication between LME structures and other organizations should be well coordinated (also in order to manage potential conflicts between organizations on the remits of their mandates).

3.2 Science needs for LMEs

The required science and information needed for LME projects will vary greatly for each LME. Some LMEs are the subject of extensive research endeavors prior to GEF initiatives. In these cases, substantial pre-existing information may be capitalized and gaps identified in the development of the TDA. Other LMEs are not as data rich and partnerships for scientific research may be established as part of the GEF-funded LME project. Scientific collaboration can also contribute to a common framework for decision-making, and can establish partnerships that can serve as a foundation for LME management actions. Common challenges can include the need to develop common research strategies, priorities and monitoring protocols, as well as overcoming reluctance to share scientific data across institutions.

3.2.1 The Ecosystem Approach and Ecosystem Based Management

The concept of ecosystem approach refers to a management regime that aims to maintain the health of the ecosystem alongside appropriate human uses of the environment, for the benefit of current and future generations. Through analyses of trade-offs, an ecosystem approach is expected to contribute to achieving long-term sustainability for the use of marine resources across sectors. An ecosystem approach serves multiple objectives, involves strong stakeholder participation, and focuses on human behaviour as the central management dimension.

Management of LMEs is by definition taking an ecosystem approach to management as its basis. Good, efficient, transparent, and participatory governance approaches support an ecosystem approach by accounting for all stakeholder interests and finding ways to resolve conflicts. Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) is an important tool of the EBM approach (see section 3.5). The TDA and SAP processes are also tools developed specifically for LMEs. They facilitate the development of governance and management actions from an ecosystem based approach (see section 3.3). Well-developed governance approaches can help identify common goals among stakeholders, providing a framework for cooperation that can strengthen governance.

3.2.2 Links:

►Taking Steps toward Marine and Coastal Ecosystem-Based Management - An Introductory Guide.

3.2.3 The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management

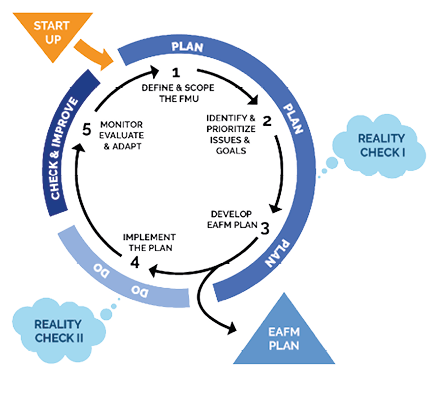

An Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM) is a practical participatory process to sustainably achieve and maximize diverse societal benefits of fisheries by balancing ecological well-being and human well-being through good and effective governance (Figure 3.2).

Conventional fisheries management focusing on single-stock management of fisheries resources does not account for the complexity inherent in ecosystems, including their human components. Ecosystem approaches aim to support decision-making, making explicit the implications for decisions made. For example, within a given ecosystem or foodweb if you harvest a certain level of predator x, what are then the implications for prey y? On the human component, there is a focus on mediation and facilitation, and improved conflict resolution, e.g. among different fisheries sub-sectors and sectors impacting on fisheries.

The ecosystem approach requires dedicated strategic interventions that promote understanding and develop capacity at community, mid-level management, and policy levels. Particular effort is required to foster, promote, and maintain interaction between the different agencies responsible for coastal and marine resource management – in particular the environment and fisheries agencies.

The need to apply an Ecosystem Approach is globally accepted since the Rio Conference in 1992, several following earth summits, and endorsed in international decision-making through various UN General Assembly Resolutions. However, it is not yet widely applied due to various reasons, among them a still persistent lack of awareness and understanding, as well as clear guidelines on how to operationalize.

Figure 3.2: Five steps of EAFM

3.2.4 Example: EAFM Capacity development and training in the Bay of Bengal LME (BOBLME)

The BOBLME Project, together with international and regional partners (e.g. NOAA and SEAFDEC), and with financial support from the GEF, Norway, Sweden and USAID, developed a comprehensive training course supporting capacity development for implementation of an ecosystem approach to fisheries management. These materials are available online, and are also in line with EAFnet, which has been developed by FAO to facilitate access to information and resources that are available at FAO on the application of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAF), including an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries toolbox.

The BOBLME project has trained hundreds of middle managers and fisheries officers through 25-30 EAFM training courses across Asia. In addition, at least 57 EAFM trainers have attended Training-of-Trainers courses acquiring the skills to train their peers in the EAFM Course. This growing EAFM cadre has the capacity to plan and implement local coastal management plans using EAFM principles. Some of this training is held in local languages, as translations into Bahasa Indonesia, Thai, and Myanmar languages have been developed.

However, due to the selection criteria of training course participants and the time required to attend the courses, most senior fisheries officers, involved in planning and policy making in the countries where EAFM is being established, have not been sensitized to the issue, nor introduced to the concepts involved. Therefore, recognizing the need for solid policy support for EAFM, and based on materials already developed by NOAA, a series of information materials was designed for Leaders, Executives and Decision Makers (EAFM-LEAD) with an emphasis on linking policy to action and facilitating policy-level support for widespread capacity development.

It is difficult to assess or even claim any cause-and-effect relationship, but in the past fewyears several governments of Bay of Bengal countries have included EAFM in their national policy planning and fisheries legislation. The most recent addition is India, where EAFM has become a principal concept in the 2017 National Policy on Marine Fisheries. The Marine Fisheries Management Plan of Thailand, the National Policy for Marine Fisheries Management 2015 – 2019 and the Fisheries Act B.E. 2558 (2015) recognize the significance of EAFM in managing the fisheries. Both Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as the Philippines, all participating countries in the Coral Triangle Initiative, have adopted EAFM and its guiding principles, and more of the regional countries are expected to follow.

If these processes are considered as taking place in parallel, they underline the need for further awareness raising and capacity development, which is addressed by this EAFM training course. The implementation of a growing number of local EAFM plans to manage fisheries is expected to lead to more sustainable use of these resources.

3.2.5 Links

►Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management toolkit

►Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries toolbox

►Essential EAFM Trainer Resource Guide

3.2.6 Example: Cooperation agreement that promotes an Ecosystem Approach in the Mediterranean Sea

In Europe, the protection of the marine environment is based on an Ecosystem Approach and is codified in the Marine Strategy Framework Directive that uses 11 descriptors of Good Environmental Status. ►http://ec.europa.eu/environment/marine/eu-coast-and-marine-policy/marine-strategy-framework-directive/index_en.htm

IIn the Mediterranean Sea LME, the respective Regional Sea Convention (UN Environment/MAP-Barcelona Convention) and Regional Fisheries Management Organization (General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean of the FAO - GFCM) have both adopted their own strategy to accelerate progress towards the implementation of an Ecosystem Approach and in support of SDG 14. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed in 2012 between the GFCM and UN Environment/MAP is an example of formalized cooperation between a UN Environment Regional Sea Convention and an FAO Regional Fisheries Management Organization. This cooperative agreement presents an opportunity to promote synergies and addresses existing challenges that hamper the sustainable conservation and development of the Mediterranean Sea through concerted cooperative actions. Joint action addressing marine environment and fisheries has the potential to pave the way for broader and more integrated cooperation, encompassing other uses of the Mediterranean Sea, such as shipping, via the involvement of other competent organizations.

The MoU between UN Environment/MAP-Barcelona Convention and GFCM addresses the following five areas of cooperation:

1Promotion of ecosystem-based approaches for the conservation of marine and coastal environment and ecosystems, and the sustainable use of marine living and other natural resources;

2Mitigation of the impact of fisheries and aquaculture on the marine habitats and species by the use of best available techniques in fisheries and the development of sustainable aquaculture;

3Identification, protection and management of marine areas of particular importance in the Mediterranean (hot spots of biodiversity, areas with sensitive habitats, essential fish habitats, areas of importance for fisheries and/or for the conservation of endangered species, coastal wetlands); and

4Integrated maritime policy with a special emphasis on marine and coastal spatial planning, and integrated coastal zone management, and other integrated zoning approaches, with a view to mitigate cumulative risks due to reduced access and availability of space affected by multiple and increasing conflictive uses; and

5Legal, institutional and policy related cooperation.

3.3 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis/Strategic Action Programme

The development of a science-based Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and a negotiated Strategic Action Programme (SAP) are two core activities required for all the GEF International Waters Large Marine Ecosystem, freshwater and groundwater projects.

A TDA is a multisectoral analysis that provides the factual basis and scientific justification for the Strategic Action Programme, which is usually a negotiated programme of action addressing policy, legal, and institutional reforms that address the underlying causes of issues of concern identified in the TDA. National Action Plans (NAPs) may be developed and adopted by countries as a mechanism to institute reforms at a national level, thereby contributing to the multinational goals of the SAP.

TDAs and SAPs may be developed in different ways. Some TDAs are more science-based than others, while some are relying on desktop studies or are based on novel research. In some regions of the world, national reports have been developed first, to inform the regional TDA, while in other areas, the TDA has been formulated as a regional study and later validated through national process. In LME regions, TDAs often make use of five modules of spatial and temporal indicators of ecosystem health (i) productivity, (ii) fish and fisheries, (iii) pollution and ecosystem health, (iv) socioeconomics and (v) governance.

There is no single standard approach to the TDA/SAP process; each water body ecosystem and management regime is unique, and the process is flexible enough to allow the TDA and SAP to be developed in the most appropriate way.

The following are some of the key underlying principles incorporated into the TDA/SAP approach:

•Full stakeholder participation

•Joint fact-finding

•Transparency

•The ecosystem approach

•Adaptive management

•Regular updates to the TDA process

•Action that takes into account social and economic root causes of the problem

•Accountability

•Inter-sectoral policy building

•Stepwise consensus building

•Subsidiarity

•Incremental costs

•Donor partnerships

•Government commitment

The LME Strategic Approach Toolkit describes the strategic approach to designing an LME project, incorporating an updated 5-module ecosystem approach, and the TDA/SAP process, as well as complementary tools such as ICM, MSP, the Ecosystem Based Approach to Fisheries across multiple scales, the development of MPA networks and fisheries refugia as well as climate change concerns.

3.3.1 Links

►International Waters Managers’ Insights Regarding the Global Environment Facility (GEF) International Waters Program Study: Transboundary Analyses, Demonstrations, Sustainability and Lessons Learned

►GEF IW:LEARN TDA/SAP methodology, Vols 1,2,3

3.3.2 Example: Benguela Current Commission

The The Bengulea Current LME (BCLME) Program has three participating countries: South Africa, Namibia, and Angola. The SAP, developed through the BCLME Program for the sustainable management of the region, specifies that to implement the actions agreed upon in the document, existing regional mechanisms for cooperation must be strengthened; thus, the document establishes the BCLME Program as an international body in terms of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The SAP also established the Interim Benguela Current Commission, which, in 2013, became the permanent Benguela Current Commission (BCC) with the signing of the Benguela Current Convention. The objective of the Convention is to “promote a coordinated regional approach to the long-term conservation, protection, rehabilitation, enhancement and sustainable use of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem, to provide economic, environmental and societal benefits.” The Convention also establishes General Principles for the parties to adhere to, including a cooperation, collaboration and sovereign equality principle.

The Convention establishes a Ministerial Conference made up of the Ministers authorized by each Party to attend, a Secretariat, and a Commission - the BCC. The BCC includes permanent Committees to the Commission, including an Ecosystem Advisory Committee, a Finance and Administration Committee, and a Compliance Committee. The BCC also establishes the Small Pelagic Working Group as another permanent regional structure. These Committees are made up of experts appointed by each party. Each Party to the agreement may also appoint national coordinators. The Convention specifies its relationship with other international instruments, stating that it shall not alter the rights and obligations of the parties arising from other agreements.

3.3.3 Links

►Benguela Current Commission publications

►The Benguela Current Convention

3.4 Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is a process for the on-going management of the coast, including both marine and terrestrial parts of the coastal zone, using an approach that integrates all aspects, including the various sectors of management, stakeholders, and the geographical/political boundaries, in an attempt to achieve sustainability. The Mediterranean ICZM Protocol, signed in 2008, defines ICZM as a ”dynamic process for the sustainable management and use of coastal zones, taking into account at the same time the fragility of coastal ecosystems and landscapes, the diversity of activities and uses, their interactions, the maritime orientation of certain activities and uses and their impact on both the marine and land parts.” ICZM aims to balance and reconcile, through science-based, economic, legal and regulatory tools, the numerous and often competing interests of coastal natural resource users (mineral extraction on the shelf, fisheries, marine transport, industrial and agricultural development of the coastal zone, resorts, reserves, etc.).

3.4.1 Example: Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem

The Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem (HCLME) is a significant biologically diverse area supporting one of the world’s most productive fisheries (18-20% of the global fish catch). It is under threat from pollution, habitat degradation, and overfishing. In order to build long-term resilience, representatives from Peru, Chile and other project contributors are working on a coordinated framework that provides for improved governance and the sustainable use of living marine resources and services.

This framework includes planning and policy instruments for ecosystem-based management (EBM) to provide the framework for Chile and Peru to take into account multi-disciplinary, inter-sectoral considerations and the complexities and interrelationships of HCLME subsystems and trophic linkages when defining the plans and programs for managing living marine resources. This involves capacity building pilot projects identifying tools, mechanisms and improved managerial, technical and enforcement capacities for institutional implementation including integrated coastal zone management and marine spatial planning that involves the establishment of marine protected areas.

The HCLME project has reached a milestone of success with the expansion of Coastal Marine Spatial Planning to three regional pilot projects in Peru in the plan of work for the next 5 year phase of the Humboldt Current LME.

3.4.2 Example: Mediterranean Large Marine Ecosystem

The Mediterranean coastal zone is an area of intense activity, an area of interchange within and among physical, biological, social, cultural and economic processes. Changes at any point in any part of the systems can generate chain reactions far from their point of origin. The sustainable use of resources can be seriously affected by anthropogenic or natural events or processes, such as population pressure, development projects, oil and chemical spills, climate change, natural disasters, which combined can cause significant cumulative impacts. Planning and management of the terrestrial and marine areas off the coastal zone remain rigidly divided between policies, administrations, and institutions.

In such a setting, the ICZM process provides an efficient coordination of the wide range of sectoral policies and institutions in charge of their implementation, thus enhancing the coastal zone management systems, increasing environmental protection and allowing for timely addressing of the emerging coastal challenges.

However, the practice of ICZM is often localized, relatively short-term, and project-based. It is still largely seen as an environmental activity, and has yet to fully involve those institutions and actors responsible for the social and economic pillars of sustainability.

Acknowledging these shortcomings and aware of the need to further improve coastal management, the Contracting Parties to the Barcelona Convention (twenty-one Mediterranean States and the EU) adopted the Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean as the seventh protocol to the Barcelona Convention. The signing of this first international legally-binding instrument on ICZM in the world came after a six-year process of consultation, negotiation and dedicated work of all the Contracting Parties. Its entry into force in 2011 represents a crucial milestone in the history of the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP).

The implementation of the ICZM Protocol implies the transposition of ICZM principles, objectives and actions into national policy frameworks and instruments, the enhancement of the governance mechanisms, the engagement of stakeholders and development of partnerships, as well as capacity building and awareness raising. Furthermore, the effective implementation of the ICZM Protocol calls for complementary and coordinated actions at various administrative levels and among various sectors.

In order to facilitate the implementation of the ICZM Protocol provisions, the Contracting Parties entrusted the Priority Actions Programme / Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC - the Regional Activity Centre of UNEP/MAP dealing with coastal zones) with the role of the main coordinator and provider of the technical support.

On the occasion of the Barcelona Convention CoP 17 (Paris, 2012) the Contracting Parties adopted the Action Plan for the implementation of the ICZM Protocol in 2012-2019 with the aim to speed up its implementation through country-based planning and regional coordination.

3.4.3 Links

►Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority - Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report

►Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean

►http://www.pap-thecoastcentre.org/about.php?blob_id=56&lang=en

3.5 Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) has become an important planning process for dealing with the increasing uses of the world’s oceans and the need to protect and conserve marine biodiversity. MSP activities have been initiated in North America, in some parts of the Pacific, and, in particular, in European sea-basins as well as many other parts of the world. It provides an operational framework for the implementation of an ecosystem based management approach to spatial and temporal uses of the marine environment. The European context provides an important example of how MSP has been tackled in a transboundary context.

Environmental planning activities and regulations are increasingly being considered farther offshore in conjunction with historical efforts in ICZM. The EU Maritime Spatial Planning Framework Directive (MSPFD) coupled with the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD), both being instruments of the European Maritime Policy, also provides the policy basis for an ecosystem approach to the management of human activities.

In the European approach there is a strong link between MSP as planning instrument and related marine policies as well as sectoral policies (covering environmental policies as well as policies referring to specific maritime economic sectors). As defined by UNESCO-IOC, MSP is described as:

«a public process of analyzing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that have been specified through a political process.» (Ehler and Douvere, 2009)

In MSP, management of human activities in the marine environment requires that the spatial and temporal management measures enable human activities while protecting significant elements of the environment which include ecosystem services that are valued by people. Such management measures are not only based on the environmental concerns. They also include sector specific operational and safety requirements stipulated in legislation, policy and/or standard operating procedures. Environmental concerns or constraints include the protection of ecosystem services and conservation of marine areas where requirements may be stipulated in legislation, policy and community engagement.

Therefore, MSP is primarily an exercise that brings together complex sector and environmental policy frameworks with future development objectives. In addition to engagement activities with stakeholders, maritime spatial planning also requires substantial policy analysis in collaboration between the competent authority for MSP with other competent authorities, all working within a particular governance structure and underpinned by scientific advisory processes.

The competent authority for MSP will be different across scales. Competent authority at national level is often delegated to a national ministry of environment, spatial planning, agricultural, transport, or maritime issues. At the local level, relevant sector organizations will need to engage. At transboundary scales cooperation between relevant sector specific organizations may be required. At sea-basin level Regional Seas Conventions may provide guidance and advice on MSP. MSP at the high seas level may be non-binding but can still be effective by the inclusion of specific international conventions, inter-governmental organizations, Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, etc.

3.5.1 Tool: MSP Frameworks

There are many different approaches to developing marine spatial plans. The IOC-UNESCO guide (Ehler and Douvere, 2009) has been particularly influential, as it provides a standard methodology or step-by-step guide to MSP. This guide builds on number of good practices extracted from planning efforts worldwide. The guide lays 10 steps for MSP implementation. MSP does not lead to a one-time plan, as its steps are not linear but rather part of the continuing, iterative process that learns and adapts over time. In the EU context, BALANCE Project has proposed cyclical approach to MSP development (Ekebom, 2008).

Figure 3.3 Planning cycle as developed by the BALANCE project (Ekebom, 2008)

Work by Gold et al. (2011), representing the consensus of an international working group, identifies a series of good practices for MSP process implementation. This study discusses steps in detail starting from initial conditions such as drivers, authority, efficiency, and financing, but also planning practices itself including stakeholder participation, data management, and plan development, and finally, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. Similarly, European Commission MSP Framework Directive recommends that MSP should cover the full cycle of problem and opportunity identification, information collection, planning, decision-making, implementation, revision or updating, and the monitoring of implementation, and should have due regard to land-sea interactions and best available knowledge. This full cycle approach to MSP is provided to Member States as general guidance on how to develop, implement, and monitor their MSP processes. However, no single approach fits all and “the form that maritime spatial planning takes varies considerably between, and even within, nations, but a number of characteristics are universal” (Jay, 2010).

In reality, the launch of an official national MSP process creates a substantial set of challenges, many of which somewhat coincide with the ‘steps’ defined in the IOC-UNESCO guidelines (Figure 3.4):

•Step 1 legislative and organisational structures and responsibilities need to be clarified;

•Step 3 processes for horizontal and vertical coordination across government (multi-sector / multi-level / multi-jurisdictional / land-sea), including the incorporation of departmental policy priorities, need to be established;

•Step 4 processes and formats for engaging with non-governmental stakeholders and communities need to be developed;

•Step 5 a common understanding of the ecosystem approach needs to be established;

•Step 5 an inventory of relevant data and their sources has to be drawn; processes and tools for collecting and analysing the data for MSP purposes have to be developed;

•Step 3 policy priorities for marine/maritime sectors have to be understood and MSP objectives have to be agreed; and

•Step 2 financing, resources and expertise have to be secured at a time where both individual as well as institutional capacities on MSP are lacking

These challenges are even more apparent when it comes to cross-border cooperation between countries within a given region. In particular, the EU MSP Directive calls upon Member States to ensure transboundary cooperation between those sharing a sea space and to promote cooperation with third countries. Within the Baltic Sea region, the HELCOM-VASAB MSP working group has adopted ‘Guidelines on transboundary consultations, public participation and co-operation’. These are, however, not legally binding. Thus apart from the general obligations under UNCLOS, the Regional Sea Conventions and the ESPOO Convention, there is still so far no agreed framework on how to pursue cross-border consultation and cooperation with regard to MSP. Almost everywhere around the globe, bi- and multi-lateral mechanisms for sharing data, engaging with stakeholders and discussing priority policies across borders need to be established. Critically, these need to take into account that 1) countries have diverse planning cultures and governance structures, 2) different conditions and priorities, 3) are at varying stages of the MSP process (if it has at all started), and that 4) consultation for the coordination of specific marine spatial plans requires a different process to that needed for more general cooperation about MSP processes.

Figure 3.4 Step-by-step approach for MSP as outlined by IOC-UNESCO (Ehler and Douvere, 2009)

A specific Marine Spatial Planning Toolkit has been developed to provide an overview and practical tools to support MSP in LMEs. It focuses particularly on MSP across management boundaries.

3.5.2 Example: Marine Spatial Planning- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

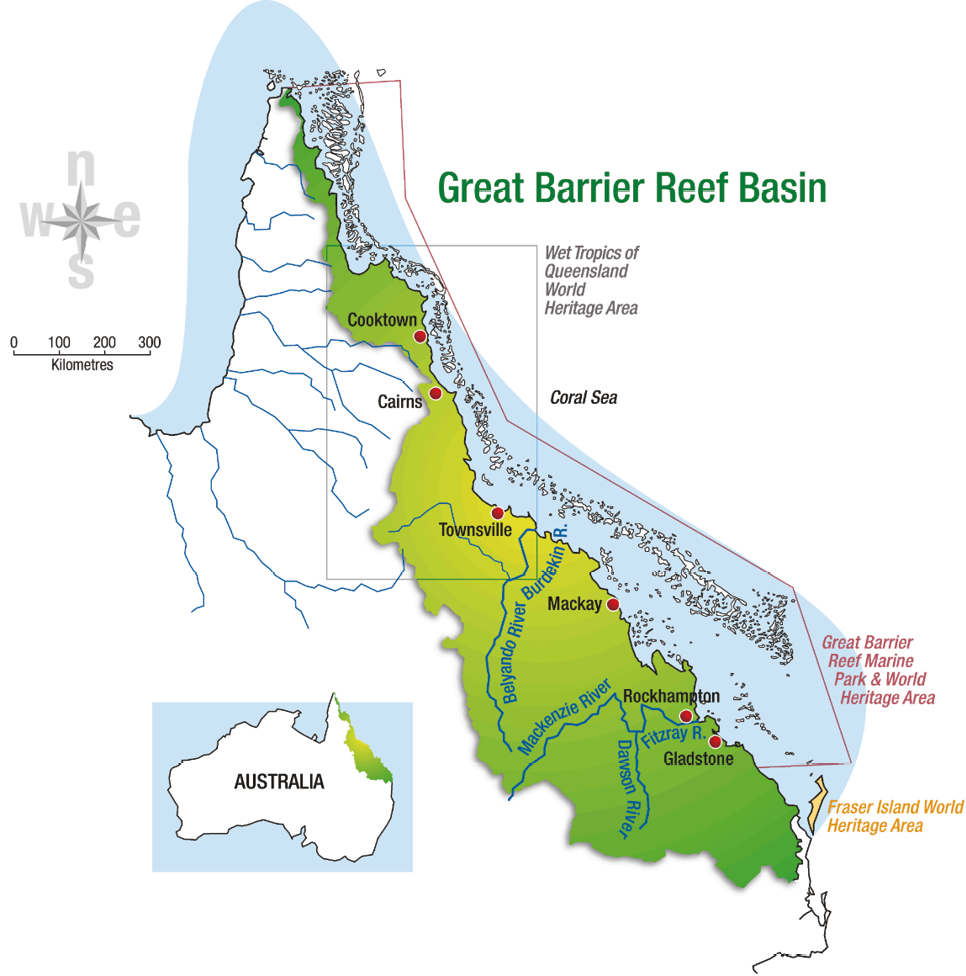

One of the pioneer examples of MSP is the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP), Australia and was established by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act of 1975. The total area of GBRMP is 344,400 km2. The GBRMP is one of the largest, richest, and most diverse marine ecosystems of the world. The reef spans a length of 2300 kilometres along two-thirds of the east coast of Queensland and represents about 10 percent of the world’s coral reef areas.

The GBRMP brings billions of dollars into the Australian economy each year, and supports more than 50 000 jobs. The catchment area adjacent to the Reef comprises 22% of the Queensland’s land area.

There are more than 70 traditional owner groups along the Reef coast and their custodianship extends to marine resources and the sea and islands. Due to its natural as well as historical significance the Park has been included in World Heritage list since 1981.

A comprehensive and adaptable spatial panning system exists to manage and protect the GBRMP. Spatial Planning is one of the cornerstones of the GBRMP’s management strategy to maintain the biological diversity and ecological systems that create the marine park and to manage the impacts of increasing recreation and expanding tourist industry and to manage the impacts of risks of pollution and shipping. Zoning in the GBRMP is a legislative instrument in its own right as well as being the key to its planning.

The adoption of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 (hereinafter the Marine Park Act) is a significant milestone in that it provides a strong legislative basis for the protection and management of marine and coastal resources in the Reef region. In addition, various complementary plans and policy guidelines have been adopted subsequently to provide better protection of the ecosystem in the Region.

The Marine Park Act provides a special regime of conservation and multiple use of the Reef which ‘includes spatial management of a large marine ecosystem through zoning with powers to deny, or impose limiting conditions on, use of or entry to all part of marine commons with in the Marine Park’.

Figure 3.5: Boundaries of the Great Barrier Reef Basin

3.5.3 Links