4. Stakeholder Engagement in Transboundary MSP

As is the case for any national MSP process; good stakeholder engagement may be the key to providing the full set of benefits of a transboundary MSP process. These benefits may extend beyond the actual spatial planning decision. Furthermore, especially in light of potentially limited statutory mechanisms to enforce results of a transboundary MSP process, a stakeholder process is also key for actual implementation of the plan.

Identification and engagement of relevant stakeholders as early as possible is necessary for ensuring that the plan has broad relevance and buy in. Stakeholders are also valuable sources of information for plan development and decision-making process 5 . Bringing stakeholders into the process early on and raising awareness of the intent and scope of transboundary MSP is important, especially when it is assumed that not all stakeholders are familiar with the concept.

Overall it should be clearly defined to what extent stakeholders will ultimately have a ‘say’ in the process - whether they will be merely ‘informed’ (on the lower end of the scale of stakeholder engagement) or whether they will even have power within the decision-making process 5 . In view of transboundary processes it is highly likely that such engagement can only reach up to the ‘involvement’ level.

Whereas the benefits of stakeholder engagement are the same as in any national MSP process, the type of stakeholders to be engaged, as well as the engagement method, may differ substantially depending on the scale of the MSP process. Checklists and tips for how and when to engage stakeholders across multiple levels can help with designing and ultimately carrying out the process (see example 4.1.1).

Several synergies exist between this chapter and the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit. Links with specific sections have been identified below.

4.1.1 EXAMPLE: Handbook on multi-level consultations in MSP (PartiSEApate)

The Handbook was developed within the context of “PartiSEApate – Multi-level Governance in Maritime Spatial Planning throughout the Baltic Sea Region”. It provides an insightful checklist of tasks that MSP organizers should perform at different stages I process together with stakeholders at multiple levels. It emphasises the importance of MSP focal points in each country to facilitate cross-border consultations and describes the respective roles and tasks of the multiple players within a transboundary MSP process. It is meant to help maritime spatial planners decide ‘why and how’ to involve stakeholders from a given level at an appropriate time in the planning cycle. The handbook has a universal character: although it was developed based on the experience of the Baltic Sea Region countries, it can be applied in other EU sea basins and other parts of the world.

►Handbook on multi-level consultations in MSP (PartiSEApate project)

4.2 Stakeholder Identification

The information gathered during the analytical stage (Chapter 5) can be used as the basis of a thorough stakeholder identification and analysis. This should concentrate on the transboundary dimension of maritime activities, who may or may not be positively or negatively affected by any change resulting from the MSP process, as well as the respective power of each stakeholder institution.

Identifying stakeholders with an interest or stake in a transnational MSP process normally depends on main reasons for their engagement, stakeholder participation traditions in a country as well as on other national policy/project objectives. Further information on ways to define and categorize stakeholders based on their reasons for engagement can be found in the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit Chapter 3. Several indicators in section 2.1 of the LME-LMSA Scorecard Indicator Framework may also be helpful for stakeholder identification and development of an engagement strategy.

An initial step is to develop a comprehensive list of stakeholders from governments, sectors, and interest groups. To identify ‘key’ stakeholders, an analysis of stakeholder relevance to the process should be done based on agreed criteria (see example 4.2.1). Additional tools for mapping stakeholders can be found in the Stakeholder Engagement Toolkit Chapter 4.2.1 Mapping, Assessing and Engaging Stakeholders.

4.2.1 EXAMPLE: Stakeholder selection (ADRIPLAN)

The ADRIPLAN project used stakeholder identification and mapping approach to identify different categories of stakeholders, from various national and international governance tiers with relevance in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. A preliminary stakeholder list was compiled from all countries, departments and institutions and transformed into a common database, which can be updated whenever necessary. The selection of stakeholders reflected the maritime sectors, users and interest groups active in the planning area, from statutory, regulatory and non-statutory perspectives, in order to achieve broad acceptance, ownership and support for MSP. The list was structured to group different categories of stakeholders according to their sectors, interests, and themes. The selection reflected all of these actors and their respective organization(s) or representative. As a next step, key stakeholders were identified, as well as the most appropriate method to engage with them (interviews, information requests, workshop participant, etc.). The selection of key stakeholders considered those that are entitled to take part in the planning process and discussions using weighted criteria. The following criteria were used, which may be useful in other transboundary MSP projects: decision-making power of the stakeholder; representation across sector and government levels; knowledge of the issues being discussed, as well as their experience and willingness to cooperate.

►ADRIPLAN Conclusions and Recommendations

4.3 Stakeholder Engagement Strategy

The stakeholder engagement strategy in general concerns the decisions about whom to involve in the transboundary MSP process, in what ways, when, and for what reasons. While considering the wide pool of stakeholders in the selection process is important, engaging a large number of stakeholders is not necessarily a key to success. In fact, a careful stakeholder selection process, right timing and a well-designed engagement strategy is more important for MSP process outcomes.

The combination of appropriate methods to include in a stakeholder engagement strategy closely depends on the type and number of stakeholders identified as relevant to the process (see example 4.3.1). The ladder of engagement presented in the Governance Toolkit Chapter 2.3: Stakeholder Engagement and the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit Chapter 2.1.3 provides a general framework for designing a strategy. The stakeholder engagement strategy in a transboundary MSP process should consider some special considerations, described in the following sections:

First, stakeholder engagement in a transboundary context may very likely refer to institutional stakeholders rather than individual sector representatives (maritime users), who are likely to be targeted at the given local or national scale. The majority of stakeholder engagement – even on issues of relevance for the transboundary MSP scale - may be more effectively handled by each national partner involved, in light of varying stakeholder engagement cultures and power relations.

Further offshore maritime activities generally hold less stakeholder interest than nearshore activities. Transnational MSP processes – unless focusing on nearshore cross-border hot spot areas – are likely to deal with broader scale issues, which may be situated quite offshore. Thus, more attention has to be paid towards ways of attracting the right stakeholders to engage in the process.

Rather than embarking immediately on cross-sector / cross-level engagement, sometimes it is more effective to first learn about the perspective of a single sector by engaging interested and relevant stakeholders from one sector only across the LME / marine area in question.

Stakeholder engagement is more likely to be truly effective when opportunities are identified to go to a stakeholder directly, rather than expecting them to come to an MSP related meeting. It is relevant to identify already existing relevant transnational cooperation mechanisms or even governance structures and engage and work with those rather than trying to establish new ones.

It is important to engage stakeholders in a positive way and show the opportunities available to them via an MSP process. With MSP still being a relatively new concept, there can be signifiIant insecurity among stakeholders on what to expect from an MSP process. Sectors such as fisheries or shipping, where ‘freedom of the seas’ is a traditionally inherent value, may for instance be resistant to MSP – even though these sectors’ activities span across borders and are expected to also benefit substantially from planning for emerging activities as part of MSP.

Stakeholder engagement should also be of direct value for the stakeholders themselves by providing incentives as reciprocation for their own investments. Transnational stakeholder meetings require more careful planning as they are more resource intensive. Not only may travel costs be higher, but more time is also dedicated by stakeholders to attend a meeting, potentially in another country. Therefore, when possible, engagement process should also consider what can be offered to stakeholders as direct engagement incentives (e.g. information sharing, networking opportunities, business pitches).

All issues related to language and communication barriers, which apply to the actual planning team (see 3.4.4), are even more prominent in interaction with stakeholders . This is especially due to the fact that stakeholders devote limited time to the process and information they receive needs to be understandable and to the point.

Finally, it is best to avoid stakeholder fatigue. Although it is beneficial to engage with stakeholders, they may be less interested in being continuously engaged, given their other obligations and concerns. Thus, engagement should be as effective as possible, implying:

•only a very few physical meetings;

•use of shorter / virtual methods: telephone interviews, online tools, webinars;

•interventions and engagement only with a specific group/body of interested experts;

•very good background materials, which are easy to read and visually appealing;

•offering good ‘side events’ outside the immediate scope of MSP (e.g. B2B forums interesting key note speakers, site visits, opportunities to present themselves, etc.).

4.3.1 EXAMPLE: Stakeholder analysis and mapping (Baltic LINes)

.jpg)

Figure 19. Stakeholder mapping matrix (BalticLINes 2017)

In the Baltic LINes project, stakeholders were analysed using the matrix based on several characteristics: power, relevance from a transnational perspective, willingness to participate, claim for territory and interest in transnational issues (Figure 19). The rating per characteristic was translated into scores, i.e. 3 for high, 2 for medium, 1 for low. The indicator “expertise” is the sum of power as well as relevance, while the indicator “value” is the sum of claim for space (1 for yes, 0 for no) and interest in transnational issues. The stakeholders are plotted in circles in the matrix according to their expertise and their willingness to participate. The latter ranking is directly taken from the stakeholder analysis. The value of each stakeholder is expressed by different sizes of circles. The basis of their legitimacy (legal, economic, political, scientific) is expressed through a colour code. The location of the plotted stakeholders in the matrixes quadrants indicates how they should be involved; for example, direct engagement was reserved for those with high expertise and willingness to cooperate, while those who cannot much contribute to the process (low expertise) but are willing to cooperate, were to be kept informed.

►Stakeholder Involvement in Long-term Maritime Spatial Planning: Latvian Case

4.4 Stakeholder Engagement Methods and Tools

The methods and tools used as part of a stakeholder engagement strategy depend on geographical scale as well as the allocated time and budget. Commonly used methods in MSP are focus groups, workshops and online tools. The choice of a stakeholder engagement lead and workshop moderator who are neutral, unbiased, trusted and knowledgeable about the area, are essential for successful stakeholder engagement. Additionally, establishing a transparent process based of ground rules is a key for building stakeholders’ trust, openness and buy in.

This toolkit does not describe in detail multi-stakeholder engagement processes, nor does it comprehensively include all potential methods and tools. The examples included here are particularly relevant to MSP. More stakeholder engagement methods and tools are provided in the GEF LME:LEARN Stakeholder Participation toolkit, specifically in Chapter 4.2.2 Engaging Stakeholders in Planning and Strategy Development.

4.4.1 KEY RESOURCE: ‘The MSP Guide: How to design and facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships’

Figure 20: The MSP Guide (Brouwer and Woodhill 2016)

The MSP Guide: How to Design and Facilitate Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships has been launched by the Centre of Development Innovation of Wageningen University & Research with a second edition released in May 2016. The guide links the underlying rationale for multi-stakeholder partnerships, with a clear four phase process model, a set of seven core principles, key ideas for facilitation and 60 participatory tools for analysis, planning and decision making. It draws on the direct experience of staff from CDI in supporting MSP processes in many countries around the world.

The guide has been written for those directly involved in-MSPs - as a stakeholder, leader, facilitator or funder - to provide both the conceptual foundations and practical tools that underpin successful partnerships.

►MSP Guide: How to design and facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships

4.4.2 EXAMPLE: World Café workshop interaction tool

Engaging stakeholders in a world café set-up can increase their active participation. This method is suitable where there is a need to engage people in dynamic conversation and foster conditions for the emergence of collective intelligence. Initially, several tables are set up in one room, where participants may have discussions in small groups around a particular question or issue. Then, after a specific amount of time, participants are asked to switch tables and to engage in a new discussion, which begins with a summary by the table “host” or moderator of the discussions that had previously taken place at that table. In this way, specific effort is invested in cross-fertilising ideas between participants and new perspectives are encouraged and explored. In general, it is advisable to have fewer than 10 participants per table, several predefined discussion questions, a neutral moderator at each table to stimulate, but not influence the discussion, and a note taker to record the possible input. At the end of the meeting, the results are often summarised in a plenary discussion, often resulting in defined follow-up action items.

The Baltic SCOPE project (xxvi) used this stakeholder engagement method during their second thematic meeting with stakeholders when developing the Central Baltic case. Invited sector experts were paired up, and asked to switch tables together after a certain time. This ensured that each group was able to meet with all participants, thereby increasing the opportunity for discussion and the generation of new ideas. During each meeting, the groups were asked to propose the key aspects of their sector relevant to MSP, on the basis of which the next group identified the main synergies and potential conflicts with other sectors.

►MSP Guide: How to design and facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships

►Vision and Strategies for the Baltic (VASAB)

4.4.3 EXAMPLE: Visual game (MSP Challenge 2050)

Figure 21: MSP Challenge 2050 Board Game

The MSP Challenge 2050 is a visual game on MSP to encourage stakeholders to engage in a deeper understanding of other parties’ objectives. The MSP Challenge 2050 comes in two formats: as a board game and as a computer supported simulation-game. It gives insight into the diverse challenges of sustainably planning human activities in the marine and coastal ecosystem. This is an innovative format to quickly introduce the essence of MSP to outsiders, in particular politicians, decisions makers and stakeholders from various sectors using the sea space. It aims to cultivate a spirit of collaboration and shows what can and cannot be achieved through MSP. For stakeholders who are only being introduced to the MSP concept, the board game is more suitable, while the computer game is best used with stakeholders who have previous MSP experience. A board game covers several square meters and uses physical tokens representing human activities, including maritime sectors as well as ecological functions, that ‚players’ (the planners) are moving across the board, in an exercise that recreates the space that maritime sectors take up in a given marine area. Several special editions have been launched, including focuses on short sea shipping, sustainable blue development, sustainable coasts and oceans, as well as a special edition for Marine Scotland. The board game presents a fictional marine space to avoid any political tensions, and planners are assigned to one of the three fictional countries represented on the board, with the instruction to achieve ‘Good environmental status’ and simultaneously, ‘Blue Growth’, according to different specific objectives and targets. The game is best played with around 20 players and should not take longer than a few hours.

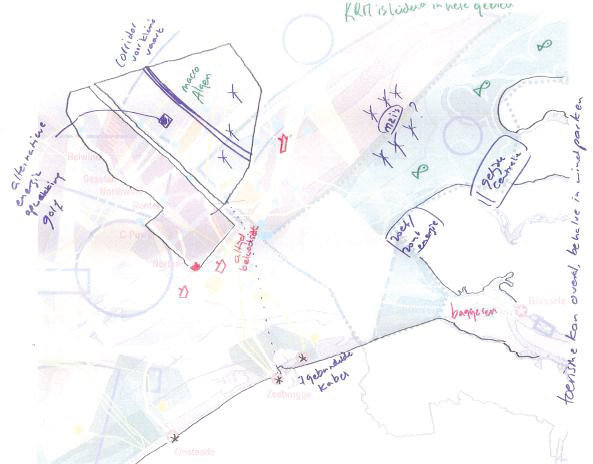

4.4.4 EXAMPLE: Sketching and visualising exercises (MASPNOSE)

Figure 22. Map drawn by Dutch MSP authority representatives. Key: Arrow = Indication of a potential conflict in the most southern part of the Belgian offshore wind concession zone with shipping. (MASPNOSE Project)

Communication tools that can be particularly useful in MSP processes include joint mapping exercises. This can be done on a very simple level, using markers and flipcharts, but can also be done with the use of computers or digital tools. For partner meetings in MSP projects, simpler hands-on mapping exercises on a big sheet of paper are often sufficient to visualise the planning process and planning options /objectives. For example, the MASPNOSE project extensively made use of mapping exercises (Figure 22). The project contributed to the consultation between Dutch and Belgian governmental stakeholders to resolve potential interferences between windmills in the concession zone and shipping lanes. For a stakeholder workshop, an overall map combining activities and uses on the Belgian and Dutch side of the Thornton bank area was produced by Ghent University to serve as a layer to draw on. During the workshop, Belgian and Dutch participants were asked to draw their priorities on this map. The group was split into Dutch and Belgian government stakeholders, each providing their own input. Afterwards the results were discussed in a plenary session. The drawings reflect very closely on-going policy developments in both countries but do not have an official status and are presented for information only. In a separate case study from the same project, interactive map tables were used as an effective way to present the underlying information and to collect input from workshop participants.

4.4.5 EXAMPLE: Online discussion platforms, social media and webinars

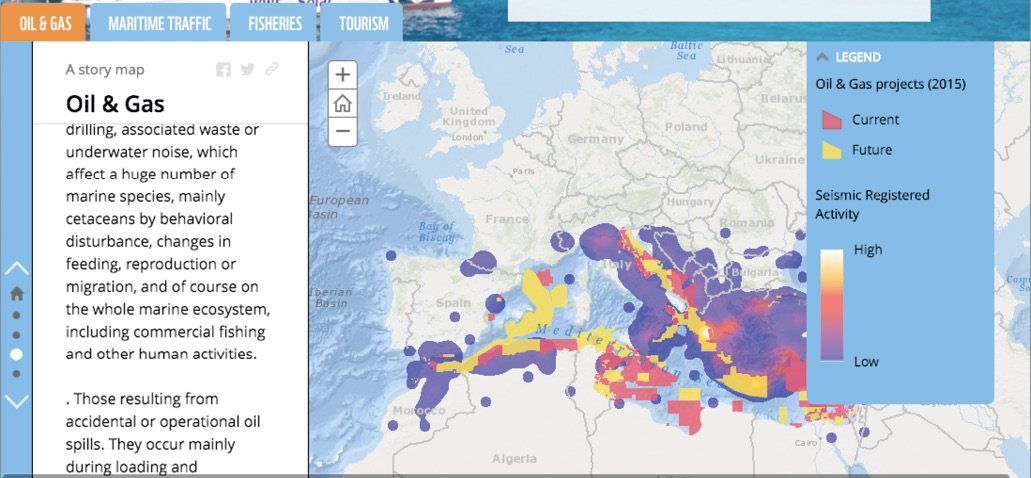

Figure 24. Example of MEDTRENDS project interactive online platform

Complementing workshops and meetings, online discussion platforms (including webinars, digital portals and websites) can be used as means of disseminating information to and communicating with stakeholders. Such tools are especially useful in a wide geographic area where engaging stakeholders in person is challenging. The websites for the ADRIPLAN, Baltic SCOPE and SIMCelt projects all include specific sections dedicated to stakeholders. On these pages, information about the organised workshops were shared, including photos and presentations given, save-the-date information, registration forms, agendas, reports and social media updates. Stakeholders were also able to make direct contact with the project partners through the websites.

Twitter or other social networks should not be underestimated as a means to communicate and gather opinions and information. Data portals and platforms are also useful tools that allow for transboundary stakeholders to easily access, share, comment and process available data, as well as comparing data sets for alignment across borders. On the data platforms, stakeholders can access clear visualizations of spatial situations that are discussed and used in the workshops and meetings (please see 5.7 & 5.8 for more discussions on data). The MEDTRENDS project, which mapped the main scenarios of marine economic development in Med-EU countries for the next 20 years, also uses an interactive online platform (please see Figure 23) to show an in-depth analysis of the current situation and future trends in four main marine economic sectors, their drivers and environmental impacts.

Webinars have also been extensively used by the US Regional Planning Bodies for engaging and informing the broader public about the MSP progress (Clean Energy Group, 2017). Throughout the webinar, participants are also able to submit comments and ask questions via the webinar Q&A feature. As many questions as possible are then answered in the 2-hour time period usually allocated for a webinar. The webinar usually has one moderator and around five panellists. Slides from the webinar are also made available to the public and everything is saved under the same channel in Vimeo.

4.5 Communication Tools for transboundary MSP

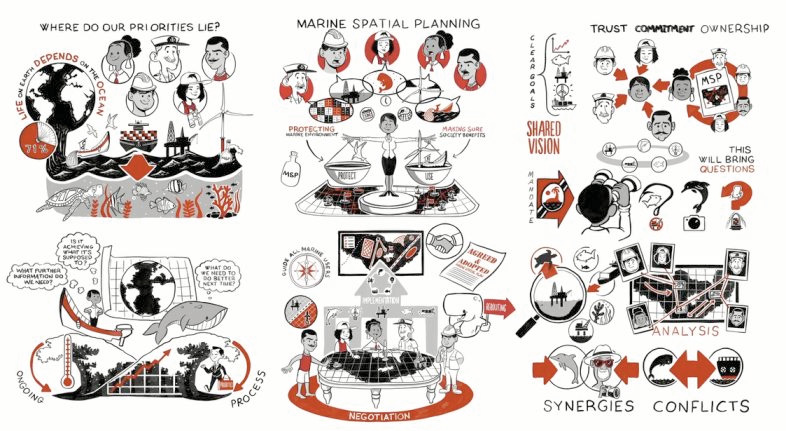

Easy-to-understand communication of drivers for and possible benefits of embarking on a transboundary MSP is an essential first step of every MSP process, including designing an MSP project in the first place. Effective communication is actually already crucial for securing the necessary funding for a transboundary MSP project and motivating the relevant institutions to become involved – either as direct project partners or stakeholders (please see 3.1 Identifying the need for transboundary MSP). For more information on communicating with policy makers, see Chapter 5.3 of the Governance Toolkit.

In general, stakeholders devote limited time to the process and information they receive need to be understandable and to the point. Moreover, innovative presentation tools are often needed to attract and keep attention. Producing simple visuals, using images, videos or even game elements to present the complex ideas or introduce the discussion topics can be very useful. Also, a humoristic element may draw attention to the actual underlying reasons, drivers and potential benefits of a MSP process.

In addition to the examples described here, the MSP Challenge 2050 (4.4.3) and visualisations of cross-border impacts and activities from TPEA (3.1.2) are also helpful for communicating about MSP in general.

4.5.1 EXAMPLE: Short films used for explaining the MSP and communicating the need for its application

Figure 24. MSP in a Nutshell video

A number of MSP initiatives have produced a short film as a tool to familiarize those to be engaged in the process, as well as the general public, about MSP. This tool is particularly useful in areas where MSP is a new concept and there is a need to define general MSP elements and principles at the outset. The video can also be used to ensure that there is a common understanding on what the MSP is about and who is to be involved.

One such film, named “MSP in a Nutshell” (2017), was produced by the global Blue Solutions Initiative and the MARISMA project in the Benguela Current region. This dynamic and easy to understand animated video was developed for a wide audience: from local communities to planners and policy-makers. To ensure broad outreach, this video is also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese and Burmese, and can be shared and viewed publicly without needing to request permission.

Depending on specific purpose and the target audience, a film can include more complex topics and have additional features. For example, the film developed as part of the BONUS BALTSPACE project “MSP Explained: MSP Challenges in Maritime Spatial Planning in the Baltic Sea Region” (2018), has an interactive feature allowing one to explore specific aspects more in depth. Nevertheless, depending on the desired complexity of the final product, its development can require several months and extensive involvement of a communication and design professional.

4.5.2 EXAMPLE: Become a Maritime Spatialist within 10 minutes (BaltSeaPlan)

Figure 25. Brochure Cover from „Become a Maritime Spatialist within 10 minutes” (WWF Germany 2010)

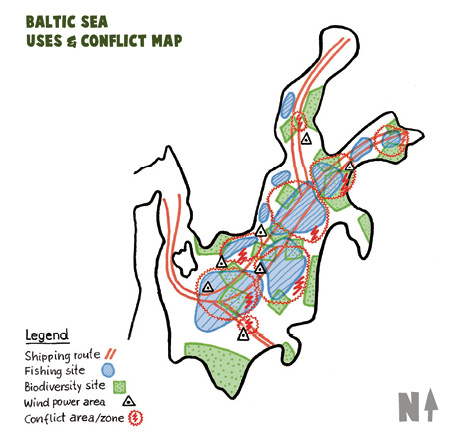

An easy-to-read, non-scientific brochure was developed by WWF Germany using a “comic” format to depict objectives and possible benefits on an MSP process, as part of the BaltSeaPlan project (Figure 25).. While MSP can be a complex topic, the images and storyline used in the brochure help present the concept in an engaging format so that it is easy to understand for non-specialists. The brochure’s content describes how planning solutions have been found through a process of involving authorities, stakeholders and interest groups to establish a formal set of regulations for all uses. It includes maps to illustrate the process of developing MSP for various uses (Figure 26).

Figure 26. Sample map from „Become a Maritime Spatialist with 10 minutes“ brochure (WWF Germany 2010)

The brochure was originally made available in five languages (Latvian, Estonian, Lithuanian, German and English) and has since been adapted for other contexts outside the Baltic Sea Region. It can be used to explain MSP to stakeholders who have previously not been involved in an MSP process.