6. Analysing future conditions developing and joint visions

Analysing and mapping current developments as part of a MSP process, provides a comprehensive picture about spatial impacts of given maritime sectors. However, it is also relevant to take into consideration possible future trends in maritime sectors, including changes in their growth and technological advancements (i.e. autonomous operations, VMS systems) which might have spatial implications beyond the usual 6 years planning horizon and/or provide new ways of information sourcing for planners. Vision and scenario processes are often used at the initial stages of the MSP process. Their aim is to anticipate changes in maritime sectors, discuss different options for the maritime space in question, and agree on a preferable course of development. These processes are beneficial for creating understanding on long-term planning objectives and on this basis aligning different sectoral priorities and defining planning objectives. Achievement of such guiding objectives may be tracked through appropriate indicators (see chapter 8), particularly indicators with a spatial dimension.

6.1 Analysing future sector developments and requirements

The analysis of national priorities and trends and the resulting matrix of interests may already include both current as well as future activities (see example 5.5.3 for Matrix of Interests). In some instances, conflicts already exist – especially those related to maritime activity(ies) and nature protection. In many other cases, MSP may be particularly helpful for preventing conflicts from occurring in the first place. Often these conflicts relate to the emergence of a new maritime use, which is requesting space at sea and may thus present a conflict for other existing sectors and/or environmental protection needs. In that sense, MSP is often not well suited to resolve current conflicts, but is rather a better tool to enable decision makers to positively shape the future development of the LME.

When assessing the spatial requirements of sustainable Blue Growth, planners should not only look at the existing maritime sectors active in the planning area and their current spatial requirements. It is equally important to look at new or emerging sectors, as well as new developments, such as technological advances, affecting the already existing maritime sectors. In particular, attention should be paid to the effects developments will have on the future spatial requirements of maritime sectors, possible changes in cross-sector relations, as well as underlying environmental conditions and impacts. Moreover ,the transboundary issues in each sector need to be considered, as well as how technical, political or social changes may affect the way spatial planners should interact with the given sectors.

There are several existing examples of maritime sector changes which can already be considered:

•The increased use of on-board data systems (VMS / AIS data) may substantially improve the availability of data on ship movements and/or fishing activities.

•The emergence of floating wind parks may substantially increase the options for where offshore wind parks can be placed, as well as reducing impacts on the environment.

•Changing government policies on how certain sectors are financed or how the licensing process is organised may have equally substantial effects and lead to sudden growth of a sector (e.g. aquaculture).

To assemble this information for an MSP process, it is helpful to develop sector analysis fiches that refer to information from the initial analysis of current conditions as well as anticipated future conditions. Sector fiches can be based on national and transnational strategies in the given LME, as well as information generated from a variety of other documents, such as industry reports, national registries as well as institutional studies. The information gathered should then be validated and supplemented by additional interviews with sector representatives. The availability of a team of professionals with solid desk research skills, a good understanding of maritime sectors as well as MSP is usually a prerequisite for developing sector fiches.

The resulting sector analysis fiches provide spatial planners with a much stronger knowledge base for both transboundary as well as cross-sector discussions. They also provide the basis for facilitating joint vision processes.

See example 6.1.1 for more information on the sector fiche development process.

6.1.1 EXAMPLE: MSP Sector Analysis Fiches (European Commission study MSP for Blue Growth)

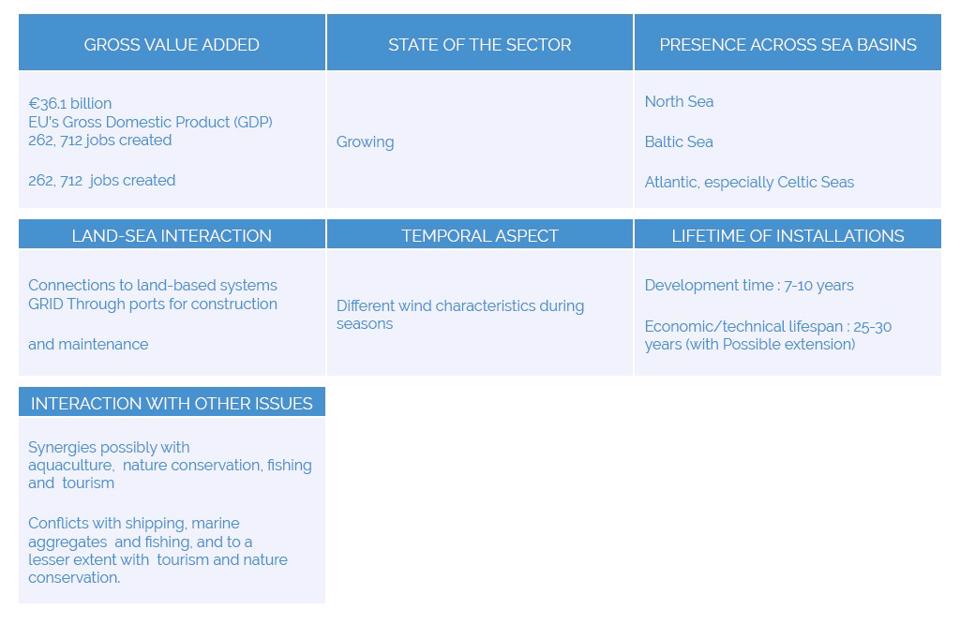

Sector analysis fiches were developed as part of a European Commission Study, titled “MSP for Blue Growth” and were published by DG MARE in April 2018 (European Commission 2017f). The nine fiches covered offshore wind energy, tidal and wave energy, coastal and maritime tourism, marine aggregates and marine mining, shipping and ports, oil and gas, cables and pipelines as well as fishing and marine aquaculture. The fiches provide an overview of future uses of the sea and the evolution of different maritime sectors, and focus not only on the present spatial needs, but also on the anticipated future developments of the sectors. In addition, the fiches look at existing interactions between the sectors and offer a set of concrete recommendations to inform MSP processes, including planning criteria

Figure 44. Sample of basic facts from sector fiche

6.1.2 EXAMPLE: Spatial demands and Scenarios (SIMCelt project)

The SIMCelt project used scenarios to understand current and future spatial demands for important maritime sectors whiles considering particular cross border issues in the Celtic Seas. The first step in such stage focused on developing sectors briefing notes for key sectors which were selected based on those which have transboundary aspects such as shipping and ports, pipelines and cables and sectors with increasing spatial demands such as aquaculture, offshore wind, wave and tidal energy. These sectors briefing notes were collated through desktop research and contact with maritime sectors and stakeholders to understand current, future trends and drivers for change.

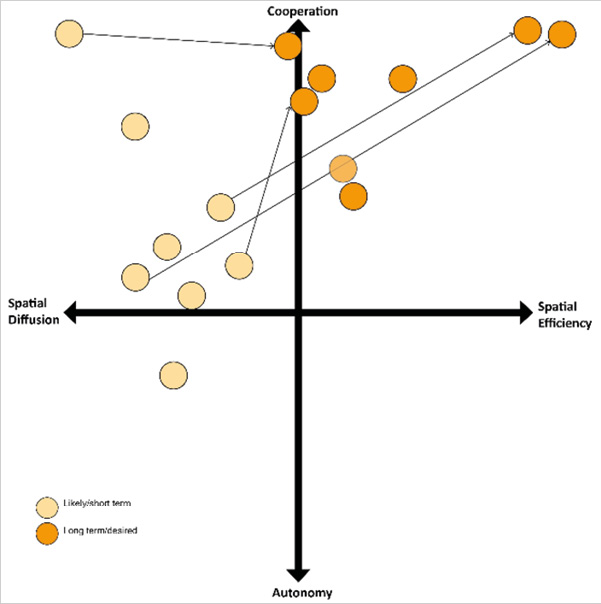

It is important that for an LME area, cross border issues and potential future scenarios are discussed between relevant actors and stakeholders. Four scenarios were developed by the SIMCelt project which considered spatial diffusion/efficiency against the degree of cooperation/autonomy between sectors and countries bordering the Celtic Seas. A workshop which involved representatives of these maritime sectors and relevant stakeholders was held to test the four scenarios and also to understand the future targets, potential changes in policy and technology and challenges in managing demand of space by these sectors. During the workshop, participants were asked to imagine likely future trends and developments in the sectors they were familiar with and place a marker on a grid of the four scenarios to indicate where they thought their sector would be by 2050 as shown in the figure below. It is also necessary that the workshop is used as a platform to discuss potential solutions to resolution were put forward.

Figure 45. Sample results of future trends analysis exercise from SIMCelt

►SIMCelt project, Spatial Demands and Scenarios

6.1.3 EXAMPLE: researching sector developments across countries (BalticLINes)

The BalticLINes project aims to improve the transnational coherence of shipping routes and energy corridors in the Baltic maritime spatial plans, to prevent cross-border mismatches and to ensure transnational connectivity. As one of the initial steps, the project has screened and analysed available information, data and maps related to past, present and future developments in shipping that are of relevance for MSP in the Baltic Sea (BalticLINes 2016). Some of the main questions answered by this analysis include:

•what are the economic, environmental and technological developments that may influence shipping in the coming years;

•what are the spatial implications of such developments;

•what are the existing plans or guidelines for the coordination of shipping traffic in the Baltic Sea?

The project will provide a synthesis of relevant information to enable in-depth discussions on common planning criteria for shipping, to develop likely future scenarios and to consult stakeholders in a comprehensive manner.

6.2 Developing a common transboundary vision

A transboundary MSP process should be guided by a shared transboundary vision exploring possible futures and choosing a preferred scenario for maritime uses. Such a process fosters a better understanding of which kind of future maritime spatial planners should plan for, and what kind of actions are required now to achieve such a future (see example 6.2.1 for a description of a vision developed for a transboundary MSP project).

The development of a vision or strategy can define relevant concepts as part of the MSP preparatory phase (e.g. maritime space and the use of maritime space), prepare stakeholder input to MSP, help prioritise the uses in maritime spatial plans and set out general planning principles. A joint transnational vision facilitates more coherent MSP across national borders based on commonly agreed elements for planning. These long-term processes also serve as a cross-border cooperation instrument. Further discussion on strategic thinking can be found in the Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 3 on SAPs and in the LME Project Cycle Toolkit Chapter 4: Preparation of Strategic Action Programme (SAP) Projects.

A well-crafted transboundary vision, which is also based on some realism, can act as a very strong bond among a transboundary MSP project group. It may enable partners, who may be stuck within the limits of their respective current remits, to gain a more positive understanding of the MSP process and their possible role in taking steps towards achieving it. A vision development process may lead to shared perceptions of the issues to be addressed, the concrete goals of an MSP and the strategies by which such goals will be achieved.

Along these lines, a vision process helps to clarify the focus of MSP and may also provide the basis to derive agreed upon SMART objectives for an MSP process. The task of MSP is to link this desired future to present conditions, e.g. by analysing the spatial implications of future sector trends and defining specific and achievable development objectives. A vision developed to supplement a MSP usually provides a long-term perspective by considering evolution of key maritime sectors beyond the typical MSP timeframe. This long-term perspective is vital for some physical infrastructures at both land and sea (e.g. offshore wind parks, port development, tourism centres). In many instances, not only do the planning periods of these sectors go well beyond the typical six-year horizon of the MSP, but also the resulting structures remain fixed for decades. Moreover, many sectors require cross-border coherence in planning (e.g. shipping lanes, energy corridors, underwater cables), and development of a joint transnational vision and planning principles has been beneficial in this regard. Such processes have also reviewed whether the national policies/strategies are compatible with each other and where synergies could be enhanced (i.e. energy corridors).

A vision for transboundary MSP can have the following benefits:

•raise awareness of emerging issues (e.g. effects of climate change, demography) and communicate the need for transnational MSP;

•stimulate stakeholder’s engagement and capacity building, particularly where MSP is a new process; and

•facilitate the discussion and agreement about joint priorities, objectives and hot spot areas that MSP will focus on;

•account for future uses not present to date and for implications of technological changes in current uses;

•enable coordination between different authorities addressing sectors and issues by showcasing common future interests;

•provide a long-term focus for MSP that may extends beyond political cycles;

•showcase positive developments and scenarios in an LME planned ‘without’ jurisdictional borders

•achieve better integration of planning across the land-sea interface.

The sector fiches described in 6.1.1 can serve as basis for visions to be developed along with stakeholders from outside the project partnership. The visions should initially only concentrate on the generally preferred, while realistic, future. Only in a second step should visions be elaborated to provide detailed contributions to the given national MSP plans and their resulting provisions, in order to achieve the preferred future. In a final step, actors may then agree on the required priority actions to be taken when implementing an MSP in the future.

It should be noted that such kind of future development scenarios may not only relate to sector developments, but also expected developments and changes in environmental conditions. These include predicted climate change effects, as well as socio-economic conditions (e.g. demographic change, political conditions, economic developments), which may relate to multiple maritime sectors (see more on scenarios in 6.3).

In general, the choice of how to develop and design a vision and related vision development process within the given LME highly depends on the resources available for a given transboundary MSP process; cooperation maturity; as well as the ultimate purpose of the exercise. It also depends on whether transboundary vision development is first solely done among the direct transboundary MSP project team, or if a selected number of interested stakeholders from outside the immediate partnership are already involved. The advantage of bringing in outside stakeholders may be to immediately draw on their specific expertise for a given sector or issue, and to showcase the objectives and potential MSP can have. At the same time, their involvement increases the level of complexity of the process and may thus not be suited for a region, where it is first of all important to create a good understanding among the direct actors of the project partnership.

In all instances, there is evidence that a ‘vision process’ as much as an MSP process requires special facilitation and moderation skills (see example 6.2.2). This is especially relevant in the transboundary context due to the increased level of complexity and possible underlying barriers to create a common understanding of a mutually desired future. The stakeholder process and vision facilitation should thus be best taken by a neutral outside facilitator (individual who is not already within the process and is not perceived as an extension of any of the involved agencies). Such skills are often to be found within NGOs, universities, as well as consultancies specialised in change management processes.

The vision development handbook described in 6.2.4 includes more detailed information on the aspects of vision development described in this section. The handbook provides a complete ‘toolbox’ in its own right, with both tools as well as multiple examples and good practices on how to develop a MSP relevant vision.

6.2.1 EXAMPLE: Transboundary MSP Vision for the Baltic Sea (BaltSeaPlan Vision 2030)

The BaltSeaPlan Vision 2030 (Schultz-Zehden et al. 2011) was developed jointly in a collaborative process in the years 2011-2012 by the project partners from the BaltSeaPlan project. These came from seven different Baltic countries and encompassed a whole variety of ministries and authorities as well as researchers and NGOs, making it a reflection of a broad range of different backgrounds and perspectives. The lead authors of the document were social science researchers and spatial planners, who had been specifically contracted to facilitate the process among the project partners.

It is a regional sea-basin wide scale vision for MSP processes, providing an integrated perspective of sea uses and the Baltic Sea ecosystem. The vision aimed to provide more coherence and certainty to all users of Baltic Sea space. Grounded in existing trends and policy objectives, it tried to anticipate future developments and changes and to place them in a spatial context. The vision is transnational, but linked to national MSP as part of a holistic approach to MSP across scales.

As part of the vision, objectives and spatial implications were highlighted for the very first time for 4 transnational topics: 1) healthy marine environment; 2) coherent pan-Baltic energy policy; 3) safe, clean and efficient maritime transport; 4) sustainable fisheries and aquaculture. It serves as an excellent example on how to translate desired future developments into concrete provisions which should be taken up by maritime spatial plans.

General steps of the process included:

1development of initial joint vision statement

2analysis of existing strategies

3development of new project ideas for unsolved issues regarding governance and management

4involvement of all BSR partners and smaller working group through series of meetings

5drafting and revision of vision text and graphics.

A pre-study was developed on future spatial needs of key transboundary sectors. The pre-study also explored links to sectoral strategies and policies, existing MSP principles (HELCOM/VASAB) and national MSPs. The scenarios were developed as part of the process and discussed at workshops. There were various feedback loops on the final text of the vision.

The BaltSeaPlan vision was the first of its kind and is still quoted. Take up of the vision was ensured through partners involved in MSP processes. The vision substantially influenced some MSP processes and outcomes in the Baltic; esp. as it developed joint sea-basin wide principles for spatial allocation decisions such as spatial efficiency, spatial connectivity, spatial subsidiarity; which have been used ever since by MS Planners.

Most importantly the vision also set the basis for the current transboundary MSP governance system in the Baltic and was one of the key documents which led to the adoption of the EU MSP Directive as it showed the importance of taking a transboundary approach to MSP. Moreover, currently ongoing projects and initiatives, which seek to create joint strategic agreement among Baltic Sea countries on how to develop the underlying transboundary linear infrastructures (shipping lanes, energy grids, blue corridors) are still resulting from this Vision process. In conclusion, the vision development process created substantial benefits for those involved by creating a strong sense of common identity between the MSP community throughout the Baltic Sea Region.

6.2.2 EXAMPLE: Coral Triangle Vision 2020 and related strategies

In the Coral Triangle, WWF is working on realisation of the long-term vision for the region that encompasses variety of aspects including area-based protection and management, reduction of negative impacts from marine activities, and improved livelihoods. The vision has been defined as: “The oceans and coasts of the Coral Triangle, the world’s center of marine biodiversity, are vibrant and healthy within a changing climate, building resiliency of communities, food security and contributing to improved quality of life for generations to come”.

Starting from this broad vision, three specific goals to be achieved by 2030 have been defined relating to 1) percentage of the area to be managed; 2) reduction of the footprint of marine activities; and 3) sustainable food security, improved income and livelihoods.

The realisation of the Coral Triangle vision and goals involves three key strategies:

1policy and advocacy - collaborating on different levels with relevant institutions, organizations, and initiatives. Six Coral Triangle nations are involved in to the process and appropriate marine policy issues are raised through the Coral Triangle Initiative on coral reefs, food security, and fisheries;

2Innovation and business transformation – seeking for new business models, innovative ways of working with fisheries, fostering collaborations and dialogues among sectors.

3Marketing and Communications - working across the region and linking up with like-minded institutions to find innovative, effective ways to let the call for sustainability be heard all over the world.

►WWF Strategies for Sustainability in the Coral Triangle

6.2.3 EXAMPLE: Visual facilitation/ graphic recording (SIMCelt and Baltic Blue Growth Agenda)

In many cases, visions are not depicted at all as a specific spatial map, but may take the form of “wild picture”, which is developed as part of the vision development process by a graphic recorder. The graphic recording is helpful as it engages people and also clearly shows the visionary character of the process, as opposed to the potentially resulting maritime spatial plan. Samples of good graphic recording are available as a resource form the SIMCelt project (xxxix) as well as the Implementation Strategy for the Baltic Blue Growth Agenda (Bayer et al. 2017).

Figure 46. Graphic Recording from SIMCelt project final conference

6.2.4 KEY RESOURCE: Handbook for how to develop an MSP Vision (MSP for Blue Growth Study)

Numerous past and ongoing transnational MSP projects have worked on developing future visions providing important input for the development of the respective national MSPs (see example 6.2.1). The Handbook for developing Visions in MSP (Lukic et al. 2018),, developed by the EU MSP Platform as part of the “MSP for Blue Growth” study, defines scenarios, forecasts, visions, strategies, action plans and roadmaps in an MSP context and how they can be used in MSP processes. The handbook presents methodological approaches used in existing and on-going processes and highlights the lessons learned. The purpose of the handbook is to help readers develop their own vision, guided by a decision framework and building blocks to compose a vision development process. The handbook is based on vision process experiences across Europe, which provide tools and practices that can be used to answer question such as:

•how to identify and analyse stakeholders?

•When and how to develop scenarios?

•How to ensure that vision process and its outputs stay continuously relevant?

Figure 47. EU MSP Platform Handbook for developing Visions in MSP

►Handbook for developing Visions in MSP

6.3 Development of multiple scenarios

A visioning process usually starts with an investigation of future trends, using methods such as forecasts and scenarios to analyse possible and/or desirable future conditions. Although there are many different kinds of scenario development techniques, the scenario process always unfolds in a broadly similar manner:

1The first phase of the scenario process deals with the identification of the scenario field by establishing the precise questions to be addressed and the scope of the study.

2The second phase identifies the key factors that will have a strong influence on how the future will unfold.

3The third phase usually examines what range of outcomes these key factors could produce.

4The fourth phase involves condensing the list of central factors or bundling together key factor values in order to generate a relatively small number of meaningfully distinguishable scenarios.

5The fifth and final phase of the scenario process can be labelled “scenario transfer” and involves applying the finished scenarios for purposes such as strategy assessment.

The scenario making process also considers identification of drivers of change and key variables (please see example 6.3.1). These drivers and variables can be environmental changes, uses and human activities, governance and management contexts. An overview of the existing maritime sector developments and their evolution across countries, in the form of a (jointly created) sector fiche, can be the first step for planners when assessing spatial requirements of maritime sectors (see 6.1).

Spatially mapped scenarios and resulting visions are usually more useful in an MSP process than non-spatial examples, but precise mapping of a large geographical area is challenging and may not be necessary for a vision process, which is more of an exploratory exercise than developing a statutory plan. The Environmental Economics Toolkit Chapter 7 provides other non-spatial assessment tools including cost benefit and multi-criteria analysis approach for scenario analysis and comparing alternative management actions. Further discussion on presenting options for management action is included in the Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 3 on TDA and in the LME Project Cycle Toolkit Chapter 3: Preparation of Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) Projects.

Most transboundary visions have used structural maps, which require less data and precision than GIS- derived maps, but still allow for identification and visualisation of main hot spots on a map. Such mapping exercises can be conducted in an interactive way, together with stakeholders or within the planning team. Interactive methods such as SketchMatch (see example 6.3.1) and visual facilitation (see example 6.2.2) have been used for participatory mapping exercises to facilitate discussions on spatial priorities.

6.3.1 EXAMPLE: Scenario Toolbox (VALMER)

Technical scenario guidelines have been produced during the VALMER project to help case study sites construct scenarios. These guidelines set out how to build scenarios in five complementary phases and provide twelve tools. The use of scenarios was seen as an effective way of moving from a theoretical framework to influencing the delivery of policy. Stakeholder engagement, via scenario building exercises, can utilise ecosystem service assessments and valuations to explore stakeholder views and preferences on various management options and trade-offs. Scenarios motivate participants to react to a plausible set of events in the future, or to build the future events themselves and then test these against a range of criteria. The criteria could be, for example, how real they are; how effective they are in delivering an outcome or whether all factors have been taken into account (Herry et al. 2014).

6.3.2 EXAMPLE: Participatory mapping exercises (SketchMatch)

A Sketch Match is an interactive planning method, involving a series of design sessions lasting up to three days. The Sketch Match session consists of forming work groups which analyse qualities, problems and potentials of a specific sea area, with an aim to identify a range of different objectives. The result of a Sketch Match is a spatial design, in the form of a map, visual story, model, 3-D GIS, visualizations, or whatever form suits the project best. The SketchMatch was developed by Dutch Government Service for Land and Water management (Dienst Landelijk Gebied, DLG). It was used to lay the basis for ‘spatial development sketches’ for integrated MSP in the Black Sea. The project aimed to develop a number of spatial draft plans for integrated flood management in the Galaţi–Tulcea region in Romania. The SketchMatch method was applied in Eforie and Sfantu Gheorghe study cases to identify and visualize potential development paths and facilitate the decision-making process for managers, policymakers and local stakeholders (Nichersu et al. 2018).