3. Designing the Transboundary MSP Process

Investing resources in good MSP process design at the forefront is important for establishing a well-functioning process for the years to follow. This section identifies guidance and tools for planning and designing a transboundary MSP process.

3.1 Identifying the need for transboundary MSP

The potential benefits of an ecosystem-based, transboundary MSP process have been well documented in numerous studies on MSP (European Commission 2010; Lukic et al. 2018; White et al. 2012; Cameron et al. 2011). Benefits include:

•Direct attention to connections within an ecosystem as a whole;

•Identifying and embracing synergies between the same maritime sector operations across countries – with many maritime activities taking place multi-nationally to begin with;

•Minimizing current conflicts between neighbouring countries and preventing them to happen in the future to come;

•More efficient government planning by achieving greater coherence as well as collaboration at an early stage – resulting in streamlined & accelerated cross-country planning procedures (e.g. strategic environmental assessment processes);

•Reduced transaction costs for maritime activities (e.g. data compilation, legal, administrative and opportunity costs);

•Improved opportunities to collaborate on cross-border infrastructure development (e.g. offshore electrical grid networks);

•Ensuring transparency and thus leading to increased acceptance of change;

•Accelerating the development of innovative, sustainable, emerging uses by taking a joint approach (e.g. bundling knowledge, resources, permissions);

•Ensuring a joint approach and coordination regarding multi-national sector organisations (e.g. IMO, MPA networks);

•Finding and addressing issues of common concern, which cannot be handled by one country on its own (e.g. climate change adaptation; oil spill risks; energy transmission lines; maritime transport; fisheries);

•Safeguarding ocean space & resource availability for future generations by ensuring efficient use of maritime space and potential co-location of maritime uses;

•Accelerating development and improving positive benefits of (national) MSP plans by combining knowledge resources (e.g. joint data use), joint SEAs, common legends, etc.

Although these benefits may offer a sufficient set of justifications for why to embark on a transboundary MSP process in the first place, current experience indicates that it is important to define a concrete set of motivations and drivers for a given LME MSP process. These should be clear enough without any detailed stocktake and/or mapping exercise, which is part of the MSP process itself. The checklist provided in (3.1.2) can guide development of a list of drivers and motivations. The LME Data Sheet and the Indicator Framework from the LME Scorecard can also serve as a guide for conducting an initial assessment of the motivations and drivers for MSP.

Table 2 provides an overview of drivers, issues and overarching objectives of some of the transboundary MSP cases around the world:

Table 2: Sample of drivers for selected cases (adapted from European Commission 2017b )

|

Case |

Countries |

Driver(s) |

|

RI Ocean SAMP |

US (RI, MA) |

State offshore wind energy targets |

|

CCAMLR |

Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, China, EU, France, Germany, Italy, India, Japan, South Korea, Namibia, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden Ukraine, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay |

Marine protection from (over)fishing |

|

CTI-CFF |

Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Solomon Islands, Timor Leste |

Reversing degradation of coral reefs, ensuring food security through improved fisheries management, addressing climate change |

|

Xiamen MFZ |

China (states within China) |

Sea-use conflicts, marine environmental degradation, lack of institutional coordination |

|

Western Baltic Sea |

Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania |

Small sea space with many different maritime uses and emergence of offshore wind industry |

|

Wider Baltic Sea |

Germany, Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Denmark, Russia |

Grey areas with disputed country borders in busy areas, emergence of autonomous shipping |

|

North Sea |

UK, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Sweden |

Establishment of super grid, joint approach to offshore wind energy production |

|

Adriatic Sea |

Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, Albania |

Small busy sea space shared by many countries |

|

Black Sea |

Bulgaria, Romania |

Joint approach Bulgaria & Romania necessary to shift old shipping lane to comply to new needs |

|

Great Barrier Reef |

Australia (states within Australia) |

Reversing degradation of coral reefs |

|

All EU Member States |

23 coastal EU Member States |

Legal obligation based on national legislation and coherence of national MSP plans under MSP Directive |

Easy-to-understand communication on possible benefits and motivations for embarking on a transboundary MSP process is an essential first step. It is a key condition for securing the necessary funding for a transboundary MSP project and motivating the relevant institutions to become involved – either as direct project partners or involved stakeholders.

A simple problem and related objective tree from a logical framework analysis may already provide the necessary information regarding drivers and motivations (see discussion in 3.3) but good visuals are also essential elements for conveying such messages. Sometimes a simple map or graph showing the transboundary interrelations between uses may already convey the basic message why a MSP process is required (see example 3.1.3). Further examples of communication tools are provided in 4.5.

3.1.1 EXAMPLE: Checklist for identifying drivers and motivations (IOC/UNESCO)

As referenced in this toolkit as well as in the IOC/UNESCO step-by-step approach to MSP (Ehler and Douvere 2009) it is worthwhile to clearly define motivations and drivers. The checklist provided in the step-by-step approach guide (Figure 11) was intended for readers of that guide to determine if the step-by-step approach would be useful for their work. Despite this original intent, it also provides a useful list of questions for those involved in an MSP process to review when developing their list of drivers and motivations. The questions can help planners in a transboundary MSP context initially identify the issues to be dealt with in MSP. This list can be refined and added to during later steps in the MSP process, including analysing conditions (Chapter 5) and defining goals and objectives (Chapter 6).

Figure 11: IOC/UNESCO Checklist for defining different needs for MSP (Ehler and Douvere 2009)

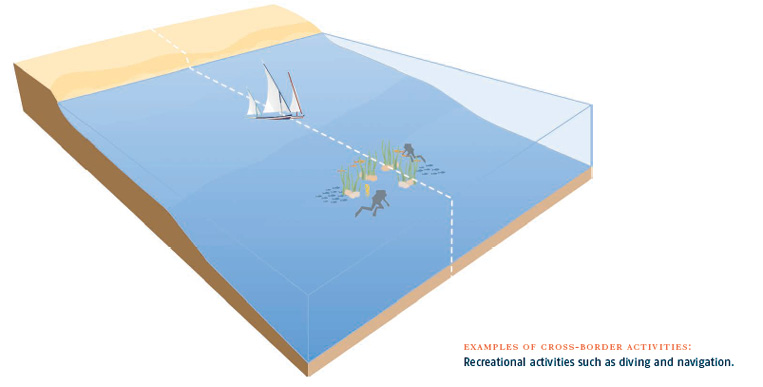

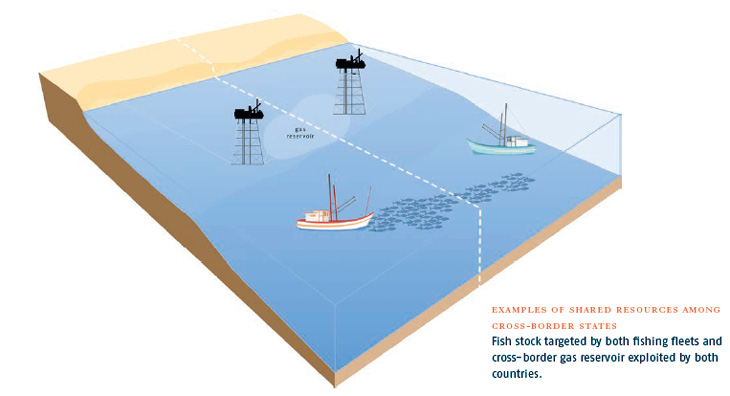

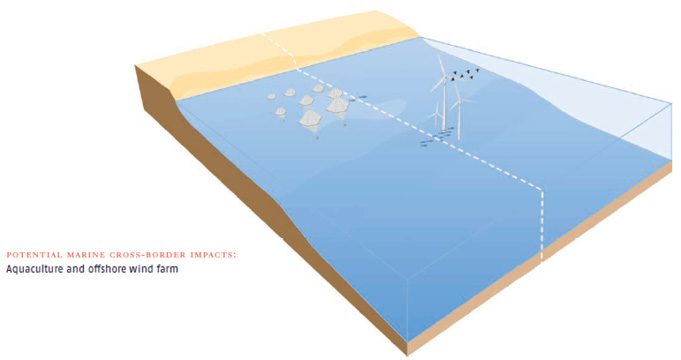

3.1.2 EXAMPLE: Visualising cross-border activities and impacts (Transboundary Planning in the European Atlantic – TPEA )

Transboundary maritime activities can lead to situations where multiple countries share and exploit the same resource, where multiple countries engage in the same maritime activity, or where one country’s maritime area is impacted by another country’s maritime activity. Understanding these cross-border interactions, their dynamics and geographic extent is a key initial step in transboundary MSP. Visualisations of these interactions can be produced to illustrate the drivers and motivations for MSP. The project ‘Transboundary Planning in the European Atlantic’ (TPEA) produced a Good Practice Guide presenting suggestions for cross-border planning exercises, including visualisations of cross border activities, resources and impacts (please see Figures 12 - 14). Developing similar visualisations can help communicate the need for MSP by illustrating different cross-border interactions.

Figure 12: Examples of cross-border activities: countries engaging in similar maritime activities (Jay and Gee 2014)

Figure 13. Potential marine cross-border impacts: countries using the same marine resources (Jay and Gee 2014)

Figure 14. Potential marine cross-border impacts: countries engaging in similar maritime activities (Jay and Gee 2014)

3.2 Establishing the Partnership / Team for a Transboundary MSP Process

3.2.1 Composition of a transboundary MSP partnership

In transboundary contexts, it is important to consider equitable representation of countries, organisations and stakeholders from across statutory (e.g. governments) and non-statutory (e.g. NGOs) MSP communities in their jurisdictions to ensure full ownership and collaboration. Building an MSP partnership for an LME should take into account the LME Governance Framework described in the Governance Toolkit Chapter 2.1.1.

Ideally, each country involved should already have an existing MSP authority which acts as the lead for MSP, according to national legislation. However, project designers for transboundary MSP have to be aware that in many cases there will not be such authority in place yet. In such cases, ideally a good ‘guess’ has to be made on which ministry / agency may later on in the process receive the leading role for developing and implementing national MSP by considering the remits, experience in strategic planning and the number of sectors that fall under the functions of the ministry/agency. For more on national coordination, please see the Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 4.2: Good practices in NAPs and national interministerial committees.

In many countries, the actual planning is subsequently sub-contracted to an expert organisation. In order to build the actual capacities in a given country, it is important to involve those institutions and sectoral agencies, who may later on be involved as expert advisors and are also equally respected by governments as well as stakeholders. Depending on the specific context, such organisations may encompass scientific organisations, e.g. universities or research institutes; consulting companies or NGOs specialised in process, project, stakeholder as well as change management processes; or experts in GIS systems and applications.

When an entity separate from the government assumes the planning role, a clear distinction should be made between them being a ‘stakeholder’ themselves in the process or acting as the maritime spatial planner. It is not helpful if the process is managed by an organisation, which in itself already has a bias towards a certain set of interests. In such cases, this partner bias should be balanced out by including other partners representing the other ‘stakes’.

While often more complex than a national process, a transboundary MSP process may also have the advantage of benefiting from cross-fertilization of knowledge sharing from the outset of the project and resulting efficiency gains. Participants may pool their skills, each leading on a certain task, allowing them to learn from each other’s expertise, especially across borders. This is particularly valid in cases where capacity is uneven among institutions within different jurisdictions. Reciprocal capacity building can be used to strengthen MSP cooperation (see example 3.2.1.1).

In summary, the partnership should as much as possible encompass partners from all countries involved, as well as represent the range of skills required in an MSP process (e.g. process management, data & information management, legal competence, stakeholder engagement, etc.) and ensure that it is not perceived as being biased towards any sector / ‘stake’ to be involved in the process.

3.2.1.1 EXAMPLE: Reciprocal capacity building through paired partnerships(Coral Triangle Initiative for Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF)

Where capacity is uneven among the institutions within different jurisdictions, a possible solution could be to pair one of the lesser capacity stakeholders with a stakeholder that perhaps has more capacity. In order to strengthen cooperation on MSP, this approach has been applied by the Coral Triangle for Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF) to enable the sharing and strengthening of specific collaborative practices. CTI-CFF a partnership made up of high-level government authorities of six countries. Regional exchanges among CTI-CFF partners allow for mutual learning and awareness raising on certain issues, such as sustainable tourism and MPAs.

►Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI- CFF)

The project should be coordinated or at least initiated by a given body or mechanism as legitimate across different jurisdictions – as this secures commitment from relevant parties during planning and implementation (see example 3.2.2.1). Even though it is not necessarily expected to be in place at the outset of a transboundary MSP project, it is highly beneficial if the transboundary coordinating body brings together the relevant established MSP authorities from the LME in question. In all instances, it is a key success factor to anchor the project into the overarching political framework and strategic processes of the given region and to work via existing transnational structures (see example 3.2.2.2). For more on co-ordinated transboundary governance, please see the Governance Toolkit Chapter 4.1 Scale of governance in LMEs.

It is not necessary that the transboundary body is taking care of the project management itself. Such a job can either be ‘outsourced’ to a neutral, professional service provider and/or can also be voluntarily taken on board by one of the involved countries. In cases where a service provider has been engaged, a professional, neutral management of the process is ensured with due regard to all transboundary / sectorial interests. With MSP being essentially a project and change management process, such an approach may have substantial advantages. Alternatively, the advantage of one country volunteering in the leading role may lead to a higher political commitment not only from the leading country, but also the other countries concerned. In this case as well, it is still an advantage if project management tasks are outsourced to a professional body.

Current examples of transboundary MSP processes show that projects and processes benefit from the creation of sub-groups, where experts for a given issue gather across the countries concerned to align activities (see example 3.2.2.3). These may either be formed directly from project partners and/or take the form of ‘associated’ advisory councils or committees (to be created or already existing) – which are outside the immediate MSP project, but meet 2-4 times per year to share information and provide advice the given MSP project. The topics for which such sub-groups may be established are highly context specific; but have previously dealt with the specific organisation and design of data portals or related cumulative impact assessment tools.

In conclusion, a transboundary MSP project is likely to benefit from an environment of trust, where planners and sectors can talk in a more informal manner to each other across countries (see also 5.7.3). The key for successfully transferring project results into formal implementation is (1) clearly anchoring the process to the political framework of the given LME and (2) take-up of at least some project results by the countries involved. Thus, project partners should filter results back to their ‘home countries’ as well as continuing discussions of results at the transnational level.

3.2.2.1 EXAMPLE: Establishing an overarching coordinating body (Rhode Island Ocean SAMP)

The establishment of a coordinating mechanism or body may facilitate the implementation of MSP processes. Examples of coordinating bodies include the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council, which was appointed as the coordinating authority for the Ocean Special Area Management Plan (SAMP). In this instance, both the state of Rhode Island and the state of Massachusetts agreed that the Council would coordinate the Area of Mutual Interest. Special legal, scientific, stakeholder, state, and federal committees were also set up to ensure ample engagement by all parties in the process. The intent of setting up legal and scientific committees was to ensure that major aspects of the Ocean SAMP initiative were reviewed, and advice provided by these experts. Unfortunately, because of the accelerated Ocean SAMP process timeline—among other factors—these two committees were not as effective as expected. Major legal and scientific decisions were necessary on a daily basis, and there was no time dedicated to set up coordinated meetings. The Ocean SAMP management team therefore changed its initial operational process, and involved legal and scientific experts from the committees individually, rather than as a group. Technical assistance was provided by experts from a local university (University of Rhode Island) who served on the management team, and attended bi-weekly meetings to assist the project leaders in overcoming political, technical, and administrative challenges that that could have stalled the process.

►Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan

3.2.2.2 EXAMPLE: ‘Flagship Status’ projects under macroregional policy frameworks (EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region)

Establishing MSP projects with a so-called ‚flagship status’ is a practice in the European Baltic Sea, in the context of the European Union Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, which is an agreement between the Member States of the EU and the European Commission to strengthen cooperation between the countries bordering the Baltic Sea in order to meet the common challenges and to benefit from common opportunities facing the region. The Strategy is divided into three objectives, which represent the three key challenges of the Strategy: saving the sea, connecting the region and increasing prosperity. Each objective relates to a wide range of policies and has an impact on the other objectives. Work conducted to support strategy implementation is organised according to “horizontal actions,” with Spatial Planning covering MSP.

‘Flagship status’ has to be granted by the two transnational bodies within the Baltic Sea, which together providing overarching political guidance to MSP in the Baltic Sea; namely HELCOM (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission Helsinki Commission) and VASAB (Visions and Strategies around the Baltic Sea). By acquiring such a status, the importance of projects is on a higher level, and such projects may serve as examples for desired future actions at both the country and regional level. Flagship projects in the Baltic Sea are often the result of policy ambitions in specific fields and can be concerned with issues of strategic regional importance. Projects with flagship status under EUSBSR aim to have a high impact on the region and contribute to the implementation of the objectives of the strategy – thus, they are rooted in a political framework which guarantees their lasting legacy.

►Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region

3.2.2.3 EXAMPLE: Specific technical or sectorial working groups / advisory bodies (HELCOM-VASAB & CCAMLR)

Technical sub-groups of a coordinating body for transboundary MSP can provide expertise on certain steps and elements of an MSP process. For example, a sub-group on the topic of data was created by HELCOM in the form of the Baltic Sea Region MSP Data Expert Sub-group. This group works under the HELCOM-VASAB MSP working group and focuses on supporting data, information and evidence exchange for MSP processes with regard to cross-border/transboundary planning issues. The group meets up to four times a year and its members include MSP and data experts, appointed by the national competent authorities for MSP.

Others examples of technical sub-groups have focused more on the creation of specific sector groups (e.g. shipping, energy, fishery) or environmental concerns (e.g. habitat advisory boards). In other cases, scientific advisory bodies have been established, including the CCAMLR Scientific Committee to which all CCAMLR members are also a member. The Committee facilitates the exchange of data from fisheries monitoring, vessel observation as well as ecosystem monitoring between its members. The CCAMLR is obligated to take the recommendations of the Committee into account in decision-making.

►Baltic Sea Region MSP Data Expert sub-group

3.3 Defining the Objectives of the MSP Project

As described earlier, it should not be expected that one MSP project can solve all issues within the given LME. Therefore, expectation management regarding what issues MSP can tackle, and which sub processes and tasks it should encompass, is important from the outset. Issues that ‘stir the pot’ may attract attention, build constituencies and bolster political commitment. When MSP offers plausible solutions to significant problems or opportunities, then political will in support of MSP is more likely to be forthcoming.

At the same time, it should be clear that the objectives of a transboundary MSP project should be attainable and realistic – not only within the given project time-frame, but also possible to achieve by using available MSP tools and the existing legal frameworks. Particularly in the crucial early stage of an MSP process, there is the danger of overloading a transboundary MSP process.

In order to promote the cause for MSP within a given LME, it is important to identify “easy wins”, which can be achieved within a rather short time frame, and then subsequently inspire the region to take the process a step further in the “next generation” MSP process. This allows for more difficult issues to be tackled in a follow-up process, and follows the inherent nature of MSP as an iterative process.

Initial issues to be dealt with may already be identified in a TDA / SAP for an LME. The results of TDA / SAP could also help identify smaller, more clearly delineated cross-border “hot spot areas” (please see 5.2.4) for which specific MSP solutions should be developed in the current or future rounds of the MSP cycle, related to a specific set of sectors (e.g. shipping lanes; energy lines, MPA networks). See the LME Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 3: The Transboundary Diagnostic Assessment and the LME Project Cycle Toolkit Chapter 3: Preparation of Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis Projects for more on this topic.

It should be noted that MSP exercises often relate to the competences and mandates of multiple government agencies, political jurisdictions and sectors, who may have a history of competition and conflict regarding their individual interests in a marine area. These challenges therefore need to be overcome through a process of compromise, leading to shared perceptions of the issues which can be addressed through the given MSP project.

The objectives for the given MSP process should be set within the context of a “vision” process for the maritime space in question, which provides the forward-looking setting which an MSP sets out to achieve. Such a vision process is normally an element of a MSP project itself, as it requires substantial skills and knowledge of stakeholders and sector developments. The development and agreement of a joint vision is a substantial effort as well as achievement of an MSP project. It would therefore be a result and deliverable of a possible 1st generation MSP project. Vision development is described in more detail in Chapter 6.2.

A clear set of goals and objectives should, however, also be set for the MSP project itself. These should be developed on the basis of the “Logical Framework Approach” (Log frame), which helps to set out systematically and logically the level of objectives and thus the hierarchy between goals, objectives and outputs (European Commission 2004).

•A goal is relevant to solving an overall problem that impacts a society or broad context. It can be described as “we know why we are acting.” A project is unlikely to completely achieve a goal, due to the fact that there are other factors which also need to be addressed – in other words, a goal is beyond the scope of the project (European Commission 2004). However, a goal provides a useful framework or point of reference for a project.

An example of a goal is to increase aquaculture production.

•An objective is the strategic purpose of a project; best described as “we know where we want to get to.” The immediate objective or project purpose is to be met with the realisation of the deliverables produced by the project, including benefits which the project intends to produce for stakeholders. It should address the central problem which a goal seeks to solve and be defined in terms of the benefits derived from achieving the objective. An example of an objective related to the example goal is to ensure space for marine aquaculture.

•The outputs are the concrete set of tangible and specific deliverables the project should produce, best described by “we know what we want to produce.”

As shown in the example of the TPEA project (see example 3.3.1), it may be sufficient for an initial MSP project to aim for an initial stocktake, identification of “hot spot / pilot areas” and/or topics, followed by detailed assessments and preparation of solutions for those. Most importantly, an initial MSP project should also provide the framework for demonstrating how solutions will be implemented and result in a continuous transboundary MSP governance framework.

In all cases, objectives should follow the SMART standard, meaning they are (Cormier et al. 2015):

•Specific – objectives should not be too broad, but rather concrete. For example, ‘protecting the marine environment’ would be a very broad objective;

•Measurable – objectives should be defined in a way that allows their quantification;

•Achievable – the objectives should be attainable within the relevant time and contexts;

•Relevant – maritime spatial planning should have influence on the defined objectives and they should be relevant to the identified needs; and

•Time-bound – the achievement of objectives should be set in a specific timeframe.

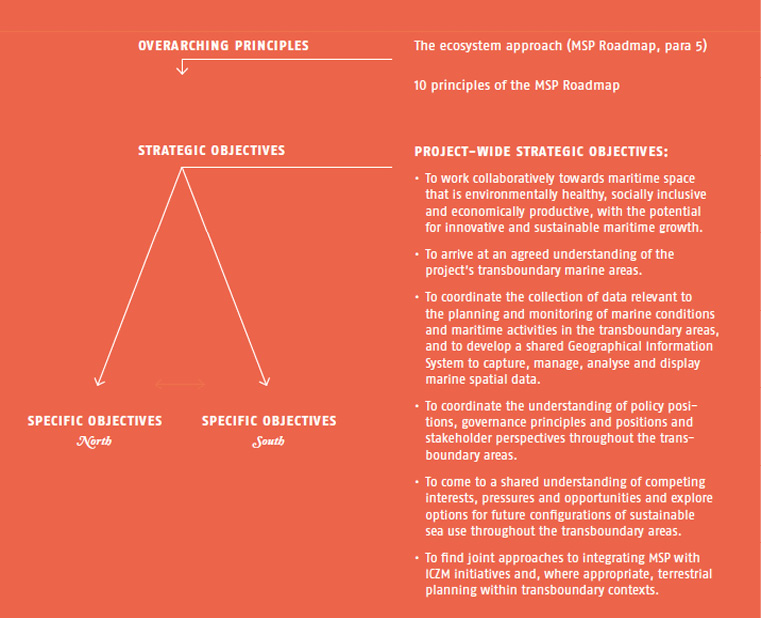

3.3.1 EXAMPLE: Setting strategic project objectives (TPEA)

Figure 15. Common principles and strategic objectives of the TPEA project (Jay and Gee 2014)

The project Transboundary Planning for the East-Atlantic (TPEA) developed six strategic objectives that applied for all aspects and phases of the project (Figure 15). The project partners accepted the ten principles from the European Commission’s Roadmap for Maritime Spatial Planning (European Commission 2008) as the basis for the project objectives. They included a common vision on what the future state of the plan area should be like, an agreed upon understanding of the transboundary areas as well as agreement on the meaning of the ecosystem approach. The project wide strategic objectives were further broken down into specific objectives for the two pilot areas of the project.

3.4 Developing the Work Plan - establishing effective communication and working structures

A clear and structured process that is understood by all relevant parties facilitates engagement and accelerates the planning process. Establishing a regular pattern of collaborative interaction and progress according to a clear action plan is important to make efficient use of resources and effectively communicate information between participants. In order to establish trust and working routines, it is advisable to start with more immediate, manageable tasks related to project objectives, delivering initial good results on those before engaging in more complex matters.

The overarching cycle of a transboundary MSP process follows the same general steps as a national MSP process:

•Preparation,

•Identification / Analysis,

•Solutions / Planning,

•Conclusions / Recommendations,

•Evaluation, and

•=> then moving into adaptation /update of MSP Process again…

Data management, communication and stakeholder engagement are ongoing elements in each step. The work plan for a transboundary process has to take into account the specific additional challenges inherent when working in a transboundary setting. These aspects are explained in more detail in the following sub-chapters..

3.4.1 Work planning and management tools

As for any project, it is important to have in place a clear work plan for the MSP project, including a plan for resource expenditures, as well as a system for monitoring progress and overall process improvement. This can include the application of management tools such as Ghant Chart, Log frame (see section 3.3), Kanban, Total Quality Management (TQM) and numerous management software.

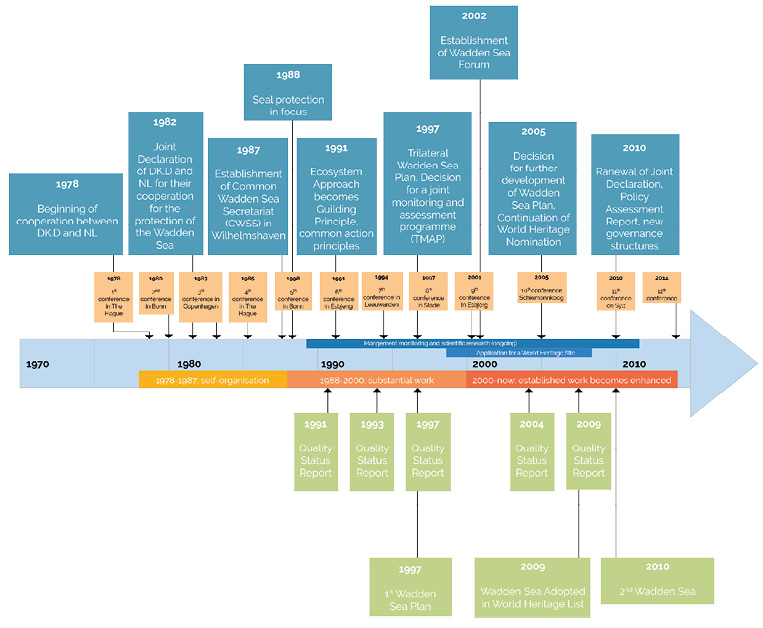

Clear understanding of roles and responsibilities can be aided by producing process/activity mapping, as well as a flowchart of responsibilities and sharing it with all involved in the project. Having project timelines and milestones clearly defined allows everyone involved to accordingly organize their schedules and manage expectations. Apart from internal processes, events and outputs, the process timeline can also include the relevant externalities that can affect the process. Such a timeline can also include the lead responsible entities/individuals for each of the expected outputs (please see Figure 16).

Figure 16. Key Events, Processes and Results of the Trilateral Wadden Sea Cooperation (Kannen et al. 2016)

Given that each organisation adheres to different rules when it comes to recording and tracking progress, it is recommended that project establishes unified reporting system. Having procedures in place (appropriate realistic and practical) for main work processes within the project ensures that everyone understand what their tasks entail, and can also ease integration of possible new members of the team. Even when carefully following work procedures things go wrong sometimes, especially if such a project is undertaken for the first time. It is therefore good to have a system in place to track where the project may have gone “off course,” so that the “next generation” MSP process can account for these lessons learned. Such a document ensures traceability and exposes the root causes of recurring problems, and allows opportunity for doing things differently in future such initiatives. Having a dedicated person or a team that ensures that that process goes in line with budgetary limits and in respect to applicable laws is also advisable.

►Learn about Quality: What is Total Quality Management?

►Kanban explained for beginners.

3.4.2 Effective and diverse meeting formats

Depending on the location of an LME, it may take more resources to conduct transboundary meetings with representatives from multiple countries than a meeting planned for a national MSP. Thus, it is important to find suitable formats and routines for meetings. Normally, countries alternate the host country for meetings as a way of cost sharing and engaging with other national stakeholders who might not be able to travel for other transboundary meetings. Further discussion on effective facilitation techniques can be found in the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit Chapter 4.2.2.1 Skilled Facilitation.

Establishing sub-group meetings, which deal with specific issues (such as GIS, specific sectors or hot topic areas) and thus also include a smaller number of specialists, has proven to be an effective method in many transboundary processes (see example 3.2.2.3).

Even though physical meetings are important and cannot be substituted, more and more transboundary projects make increasingly good use of teleconferences or web-based meetings to report on progress, especially for smaller working groups (as described above). It should, however, be understood that such remote meeting formats are best suited in cases where partners know each other already quite well, have already established a common understanding of the given task and, most importantly, speak the same language.

3.4.3 Define meeting objectives, discussion topics & supporting documents

The work plan should clearly earmark the different types of meetings (timing / location) as motivations for work to be carried out in between these meetings. Additionally, the work plan should highlight the objectives of each meeting and the respective preparatory documents, which have to be available in advance in order to reach these objectives. It should be agreed beforehand between partners on whether the meeting is designed to seek agreement on certain items, or inform each other on ongoing progress, and/or whether it is designed as a working meeting, where some partners jointly work on certain issues during the meeting itself.

A working meeting may be a very effective method as there can be time delays if open questions / activities are taken back home. On the other hand, working meetings require more time as well as participation of knowledgeable individuals or experts on a given issue. This may sometimes not be possible.

Moreover, a key success factor is identifying the same formats for partners to report to each other to allow for clear cross-sector communication. Most projects have opted for one or two project members to take the leading role to develop a blue print for a given report with subsequent rounds of comments; which is then filled with information from each country / sector accordingly.

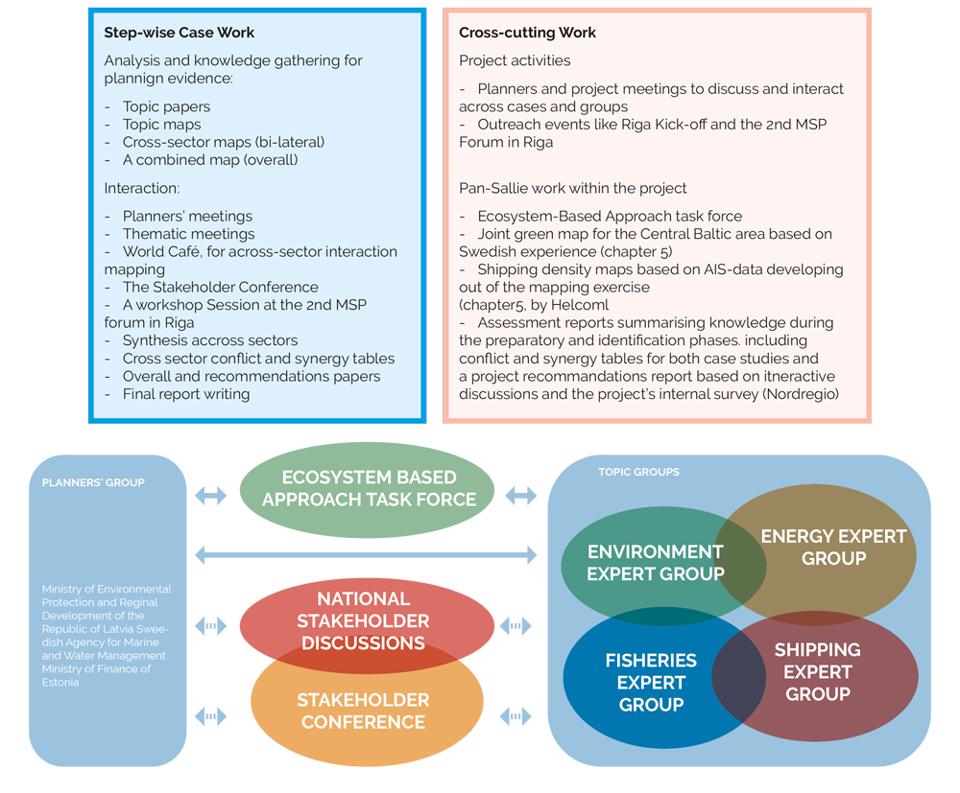

3.4.3.1 Example: Developing Meeting Schedules (Baltic SCOPE)

Figure 17. Examples of Baltic SCOPE work plans (Urtāne I. et al. 2017)

In the Baltic SCOPE project, different ‘types’ of meetings were planned (Figure 17) during the beginning phases of the project to target specific objectives and outputs. These plans included partner meetings (which involved all partners), planner’s meetings of the MSP planners from the respective countries involved, as well as bilateral and thematic meetings on particular case studies. The planners’ meetings served as working meetings on each case study. The bi- and trilateral meetings served as venues for sharing data, discussing the overlapping interests in greater detail and identifying concrete solutions. Thematic Working Groups and Meetings included experts from marine sectors to share knowledge and analyse transboundary themes such as the ecosystem-based approach and cross- sector aspects. Other sea basin wide/transboundary platforms such as the Baltic MSP Forum

were also used to engage and disseminate information to wider international organisations, policy makers and practitioners.

3.4.4 Take into account language & communication issues

One of the most obvious issues in transboundary MSP can be language differences among the countries involved, contributing to added complexity of transboundary MSP. Language is essential for communication both within the project & planning team as well as when working with stakeholders (see Chapter 4 on Stakeholder Engagement). Thus, it is valuable to remove any language barriers within multicultural, cross-border, decision-making frameworks so that negotiations can take place without giving bias to one or more parties involved. Good tools have to be put into place in order to overcome language barriers and different terminologies from national planning systems. It is important to ensure that all can take an active part with respect to spoken and technical languages. The most knowledgeable planning expert may at the same time not necessarily be the best to communicate in the project language chosen.

Finding the ‘right’ language

In transboundary contexts without a shared language, interpretation may be necessary, or an ‘international’ language not belonging to any of the jurisdictions may be preferred (see example 3.4.4.1). Rather than opting for one single language – it may also be possible to adapt the working language for the activity at hand, with due regard to equity. In case of translation or interpretation, it is worthwhile investing in knowledgeable interpreters who accompany the whole process, in order to avoid misunderstandings and misinterpretations in terminology, which can create tensions in meetings.

Create joint understanding /definitions of terms ‘uses’

Even in cases where all participants share a common language, sufficient time should be allowed not only at the beginning of the project, but also at the beginning of each meeting, to clarify and develop a ‘common’ understanding of terminology. It has been evidenced in almost all transboundary projects analysed that different interpretations of terms used were a major source for misunderstandings and barriers to reaching agreements. In view of different planning cultures and jurisdictions a term might carry a particular connotation in one setting, but be understood differently elsewhere.

Some samples of typical misunderstandings in terms used:

•The term ‘priority areas’ may for instance have a completely different meaning and legal implication in different countries and thus trigger different levels of concern.

•There are also often misunderstandings related to ‘planned activities’; e.g. activities which are not in place yet in the given maritime space in question. This can imply several meanings:

•that the ‘zone’ has already been established, but no concrete application has actually been received and may also never be received;

•or it may indicate an area for which a licence has already been granted and installation is soon to be expected;

•or it may even only mean that this is seen as a potentially suitable area for an activity under discussion – but with no formal zone having been established.

Participants should identify potential differences of use of terms; clarify meanings where necessary and potentially develop new, project-specific sets of common terms as to avoid continuous misunderstandings. A glossary of terms and symbols may be established – which then should be repeated and explained at each single meeting (please see example 3.4.4.2.)

In all cases it is worthwhile to think about effective ways of communication with each other. This may often be fostered by joint inter-active exercises. These are important both for establishing good communication within the transboundary MSP project partnership as well as in communication with stakeholders. Please see 4.4 for a description of tools to be used for MSP communication, both within the transboundary MSP partnership as well as with stakeholders and political decision makers.

3.4.4.1 EXAMPLE: ensuring a common language (CCALMR)

Defining a common working language or providing translation services is important to ensure an equitable working environment for a transboundary MSP partnership. Meetings of CCALMR and their Scientific Committee are held with translation and interpretation services, whereas working group meetings are held in English. Holding Scientific Committee meetings with translation and interpretation services enables the focus of discussions to remain on questions of scientific rigour, therefore bypassing any tensions that might negatively affect negotiations. While working group reports are translated from English into the languages of the CCALMR members, the lack of translation and interpretation services can lead to barriers in understanding and discussions at the actual meetings themselves.

►Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCALMR)

3.4.4.2 EXAMPLE: Common symbols and legends (VASAB-HELCOM)

In order to achieve minimum level of harmonization of MSP in the Baltic Sea Region, VASAB-HELCOM principles on the MSP includes adopting a joint legend and symbols which have also been undertaken at the sea basin level through the Baltic sea regional data model. This has been seen as critical in reducing existing language and cultural barriers and encourage participation of stakeholders in transboundary context. National MSP processes and projects in the Baltic such as the BaltSeaPlan have gone on to adopt these legends and symbols during the data collection/stock taking stage to foster cross border cooperation on MSP. Having these common legends are also necessary in the transboundary discussions for conflict resolution. Other projects such as ADRIPLAN and TPEA have also discussed common pictographs and symbols during the start of the project based on approaches used in previous data related projects.

►Baltic Sea Broad Scale MSP Principles

3.4.5 Build trust across borders and respect differences

MSP initiatives, especially those that span across jurisdictions, require a high degree of collaboration and commitment. Ultimately, this requires mutual respect and willingness to share power among the institutions involved. Thus, transboundary MSP depends on building openness and trust between participants, especially across borders, taking into account the different cultural contexts and learning from different approaches and priorities across jurisdictions.

Participants involved in the transboundary MSP process need to be confident that processes are transparent and their input will not only be respected, but also contribute to tangible benefits both for MSP on the whole as well as the individual user needs. While this holds true for the direct partnership, it is even more important for any kind of stakeholder involvement (see Chapter 4). Defining common principles at the beginning of the MSP process sets a clear foundation for how the process will operate, both within the partnership and among stakeholders (see example 3.4.5.1). Further discussion on these issues can be found in the Governance Toolkit Chapters 2.1.2 Evaluating Principles of Good Governance and 2.2 Values and Ethics.

As is commonly stated, trust is earned and cannot be bought. It is something which needs and should be given time to evolve - it only builds up gradually as participants work together. Such ‘growing together’ may take extra time in transboundary contexts where participants may speak different languages, operate with different cultural norms, and are accustomed to different ways and modes of working as well as styles of communication.

Therefore, the overall work plan should account for plenty of time for evolution of mature forms of cooperation (see section 3.4.1 on work planning). Project design should take into account the overall level and culture of cooperation existing in the given LME. In many instances the very first MSP project may only be designed as a process of meeting each other and establishing effective forms of information exchange; rather than resulting into concrete joint planning (see example 3.4.5.2).

Depending on whether partners are working together for the first time or not - it is worthwhile to invest in the social components of inter-action. This may not only derive from including site visits in project work, but also fostering social interaction through a conscious effort of building inter-active; more playful, elements into meetings. Such elements may not only facilitate cross-border dialogue, but also assist in lowering communication barriers between different hierarchies (junior and senior staff) within the partnership team; different disciplines as well as better integration of ‘newcomers’.

Moreover, partnerships should clearly define what should remain strictly internal, such as contents of meeting discussions or joint discussion papers, and what may later be made available to outside parties (see example 3.4.5.3). It should always be clarified whether team members, which have a formal role within their given institutions (e.g. national ministries), are acting and discussing in an ‘expert’ capacity or within the limits of their ‘official’ role. Experience shows that it many instances it is very beneficial if issues and difficulties can first be discussed internally without any further documentation to outside parties. It should then subsequently also be jointly decided which of the results can be made public via a mutually agreed statement.

Apart from these social and more process-oriented tools, collaboration is facilitated by creating a sense of collective purpose among authorities and partners involved in the MSP planning process, most notably by developing a common vision for MSP (see Chapter 6).

3.4.5.1 EXAMPLE: Principles of the Rhode Island Ocean SAMP development

Several key principles were created to guide the collaborative development of the Ocean SAMP. The principles related to the availability of information at the same time to everyone involved, and to ensure that decisions were not made behind closed doors or without input from the entire group. These principles also helped to ensure that stakeholders understood and actively supported the aims of the Ocean SAMP process. Apart from these overall process principles, Ocean SAMP stakeholder process was also led by the principles of fairness, transparency and decision making based on the best available information. Fair ground rules were agreed and followed at each of the stakeholder meeting. This has contributed to a broader commitment to the process and collaborative environment.

►Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan

3.4.5.2 EXAMPLE: Steps to scale up transboundary cooperation

As part of the PartiSEAPate project in the Baltic Sea Region, an investigation was conducted to evaluate the potential for establishing a “pan-Baltic MSP dialogue,” which would provide a forum for exchange among key regional stakeholders, including planners and sector representatives (Schultz-Zehden and Gee 2014). Based upon responses to a questionnaire used as part of the investigation, it was recommended that the dialogue should aim to build more mature forms of cooperation. The following steps, originally developed as part of the INTERACT project, offer an approach to scale up the level of maturity of transboundary cooperation for MSP as well as in general:

1Meeting: Getting to know each other, learning about motivations, interest, needs, skills, expectations, cultural and structural aspects;

2Information: Delivering (targeted) exchange of information, building basic cooperation structures and trust, shaping common ideas;

3Coordination/Representation: Creating a joint partnership structure, first allocation of functions and roles;

4Strategy/Planning: Defining joint objectives and developing concrete actions;

5Decision: Binding commitments of partners, partnership agreement

6Implementation: Joint implementation of actions, efficient joint management, fulfilment of requirements by each partner

3.4.5.3 EXAMPLE: Rules of engagement for project meetings (SIMCelt & Seychelles MSP)

Terms of reference (TOR) are normally used to set out the rules of engagement for meetings and interactions during MSP projects. The SIMCelt project and Seychelles MSP process used TOR to define the role, functions and processes of engagement and meetings between Steering Committee members which normally acts as the main decision-making group. The specific and bespoke role and functions of government, technical agencies, civil society groups and industry representatives should be considered and well defined. To ensure that meetings and interactions are effective, efficient, participatory and trust is built between partners, certain ground rules and code of conducts are necessary for ensuring open and honest communication and build transboundary working. Due to differences in governance arrangement across countries it is important that these rules of engagement/code of conduct are adapted to the existing political context and governance arrangements of each country. This is normally effective when the TOR are defined and agreed on early in the process and through consultations with the relevant LME partners and stakeholders to ensure buy in and commitment.

The Chatham House rule has also been introduced into TORs in some MSP cases to define and clarify which information and material can be shared beyond the project group meetings while engaging with national and transboundary stakeholders (e.g. Welsh National Marine Planning process). The Chatham house rule can be used to engage specific expertise and stakeholders who are not part of the project group but can be invited to these meetings where necessary.

3.5 Obtaining financial support

Implementation of MSP is the responsibility of (national) public authorities. Therefore, it is very likely to depend on public funds, both in the medium and long term. As a result, sustained commitment from government(s) to finance MSP is a critical for any transboundary MSP process to enter into full implementation. In the absence of such commitment, there is a clear risk that the whole MSP process and/or parts of it will not be implemented.

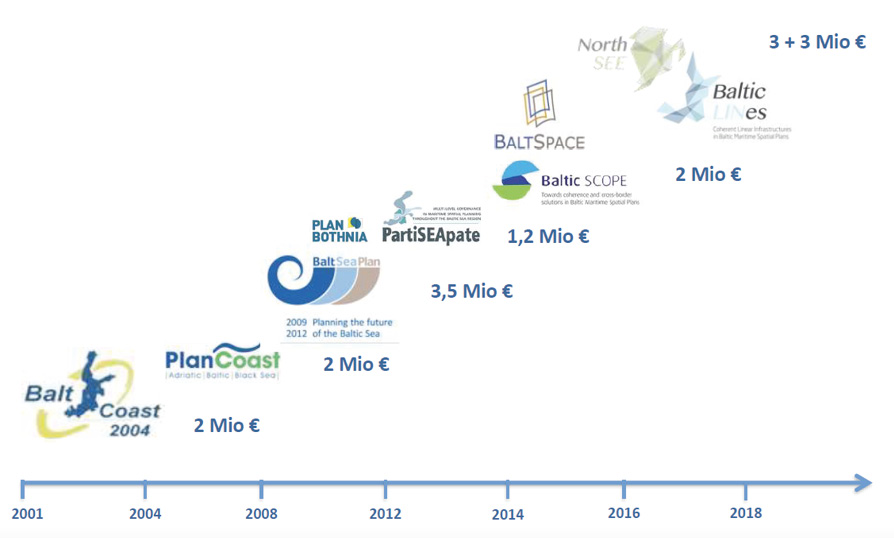

At the same time, global experience shows that the initial MSP process is very often supported by project funding, and that a strategic approach towards structuring a series of consecutive as well as parallel projects can very well lead to a sustainable funding stream, which can provide resources for preparing MSPs for official adoption by the relevant authorities (see Figure 18). Efficient recording of project achievements and communication of benefits can contribute to a stronger, sustained commitment of funders and decision makers.

Figure 18. Example of project funding stream from the Baltic Sea Region

Most often, the full implementation (e.g. putting the management, licensing and monitoring procedures in place afterwards) may indeed consequently have to come from sources independent from project funding, such as public-private partnerships (see example 3.5.1). At that later stage, it is anticipated that political commitment has already been secured, which in turn should guarantee the respective public funding. For further information about sustainable financing, please see the Governance Toolkit Chapter 2.4: Sustainable Financing; the Project Cycle Toolkit Chapter 2.6: Financing, additional costs & co-financing; and section 2.3 of the LME-LMSA Scorecard Indicator Framework.

►Indicator Framework.

Strategic coordination of parallel or sequential projects potentially funded by different sources is a task best done by the transnational coordinating body, which should act as the overarching coordinator for the transboundary MSP process (see 3.2.2 for further discussion). Countries should take joint decisions in such a forum regarding which activity(ies) should apply under which funding programme in order to secure the necessary resources.

It should be noted that MSP processes can be very much adapted to the actual resources available and that the amount of funding required highly depends on the availability of data and information, which may have already been generated under previous projects and initiatives. MSP itself is more of a political and stakeholder involvement process than a solely scientific process – therefore, initial rounds of MSP are much less dependent on (expensive) joint data portals than is often assumed.

One successful method for convincing governments to offer sustained funding for MSP processes is to identify the link to potential long-term income generation as a result of the MSP implementation, as well as fulfilment of national commitments under international environmental agreements. As such, MSP is understood as an investment (see example 3.5.2), which either ensures additional, future income sources for the government (e.g. by accelerating ‘blue growth’ activities) and/or leads to cost reductions in other action fields (e.g. by avoiding costs related to legal disputes or costly climate adaptation costs).

Transboundary cooperation in MSP may also lead to substantial cost efficiencies by merging efforts for assembling data and information (e.g. database creation). Subsequently this also implies that data used in such initiatives would need to be harmonized before being analysed and visually represented on a map (see 5.7 for data issues). Given that some of the large marine industry business organisations (e.g. energy, shipping, fishing) operate in multiple countries, there is an interest on their part to have access to a single database that adheres to a single data standard (see example 5.7.3.2). Therefore, involving the marine business community in efforts to compile data provides an opportunity to secure financial resources from the private sector.

Information on other financing and economic policy instruments including area-based user rights, permits and quotas among others relevant to MSP and LME can be found in Chapter 6 of the Environmental Economic Toolkit.

3.5.1 EXAMPLE: Debt-for-nature swap (Seychelles)

This innovative climate adaptation debt restructuring includes a strong marine conservation component used by the Government of Seychelles and its Paris Club creditors. The debt restructuring used a combination of investment capital and grants to protect and reduce the vulnerability of the marine and coastal ecosystems of the Seychelles. It is set to promote implementation of a Marine Spatial Plan for Seychelles and also ensure large area will be managed for conservation as MPA within five years.

This is an innovative financial tool to restructure debt and allow governments to free capital streams and direct them toward climate change adaptation and marine conservation activities. This debt restructuring converted a portion of Seychelles’ debt to other countries into more manageable debt held by a local entity; accomplished by refinancing the debt with a mix of investment and grants. The Nature Conservancy raised a certain amount in impact capital loans and grants to buy-back Seychelles debt. The cash flow from the restructured debt is payable to and managed by an independent, nationally based, public-private trust fund called the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT). Debt service payments fund three distinct streams: one for work on the ground that will help reduce risk through improved management of coasts, coral reefs, and mangroves, another to repay investors and a third to capitalize SeyCCAT’s endowment, which can then support conservation work into the future.

While this is a new approach for protecting marine areas, it is not unique in nature conservation (UNDP 2017); similar debt-for-nature swaps that have preserved large areas of tropical forests in Latin America. This combination of public and private funds—each leveraging the other—creates a new model and provides proof of concept for public/private co-investment debt restructuring in other areas of the world.

►Seychelles Debt Restructuring for Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation

3.5.2 EXAMPLE: MSP as an investment (PEMSEA)

Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) is an intergovernmental organisation that aims to foster healthy maritime communities and economies throughout the region. One of the ways in which they deliver this aim is by promoting impact investments: market-based mechanisms that complement philanthropy and governmental finance injections. Impact investing offers creative financing for MSP-related projects at several levels, by combining the joint efforts of entrepreneurs, with a focus on innovation and capital for the public good. An initial overview of the “investment landscape” is made for potentially relevant partners and governments to better understand the expectations of investors, as well as enabling conditions for investments. In particular, projects involved in increasing conservation efforts and strengthening sustainable practices in fisheries and aquaculture are good candidates to receive impact investments. Public-private partnerships may also combine the expertise of private companies with the facilities and capacity of the public sector. In such partnerships, private actors take on financial and operational risks in delivering a public service, in exchange for a guaranteed derived revenue stream.

One form of PEMSEA impact investment support was used for launching MSP in Xiamen, China. Although it has subsequently been supported by government funding, contributions also came from fees paid by operators that had been authorised to make use of the maritime space, if they paid a fee. They also developed a business case that demonstrated the benefits of MSP, in order to justify the need for contributions from investors.

This type of partnership may provide financial support for MSP, yet it also faces some challenges. These include a lack of sustainable cost-recovery systems for the private actors, procurement processes that lack transparency, as well as a lack of accommodating legal frameworks. Transboundary business models may be developed that outline the financing needs and address these challenges.