2. Introduction to Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning

2.1 MSP - Marine Spatial Planning

Marine Spatial Planning1 is the ‘public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that are usually specified through a political process’. (Ehler and Douvere 2009)

Over the last few years, an increasing number of nations have begun to implement MSP at various scales, from local initiatives to transnational efforts. The motivation to do so has often come from the need to find suitable space for new maritime industries; improved coordination among sectors to reduce conflicts and create synergies, or the need to stop or even reverse negative environmental trends. (European Commission 2017b).

This chapter introduces important issues for MSP in the transboundary context, which is the situation in which most LMEs are situated. These considerations are presented here as an introduction, and are further expanded and clarified in later chapters. Cross-references are included to guide the author to relevant sections where more information may be found.

2.2 Importance of issues of scale for LMEs

2.2.1 An ecosystem-based tool – but a national competence

Delineating boundaries is a fundamental part of the MSP process, as described in detail in Chapter 5 (5.2). This delineation is so far most often defined by political and jurisdictional borders, as MSP is normally conducted by national or sub-national authorities. Typically, these borders do not correspond to the limits of maritime activitiest or ecosystems.

At the same time, an MSP process is expected to apply an “ecosystem-based approach (EBA).” This approach refers to ”a strategy for the integrated management of land, water and living resources including humans and their institutions in a way that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way”2.

MSP is intended to inform the spatial distribution of maritime uses and activities in a sustainable manner that recognises and operationalises the following EBA elements (UNEP 2011):

1aligning with ecosystem boundaries;

2managing for multiple objectives/benefits;

3considering cumulative impacts;

4using best-available science and information;

5applying the precautionary approach to deal with uncertainty; and

6managing adaptively.

The application of EBA in MSP is an important issue for LME practitioners, as the majority of the 66 Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) around the world span across national jurisdictional boundaries. As a result, most LME boundaries do not always correspond to the given jurisdictional boundaries of the countries involved with potential authority over a formal MSP process. Therefore, there is the need to indicate which mechanisms and/or tools can concretely support implementing EBA in transboundary MSP, while at the same time respecting the political reality of two or more entities who are in charge of the MSP process, with each having individual jurisdiction and interests within this given ecosystem.

►Convention on Biological Diversity, Ecosystem Approach

The ecosystem-based approach is discussed in more detail in section 5.6, including examples of tools to ensure EBA is adequately incorporated in MSP for an LME. It is also discussed in the Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 2: The ecosystem-based 5-module approach and recommendations for strengthening the approach and Chapter 5 section on Ecosystem-based Management.

2.2.2 Transboundary vs. cross-border and multi-national vs. sub-national

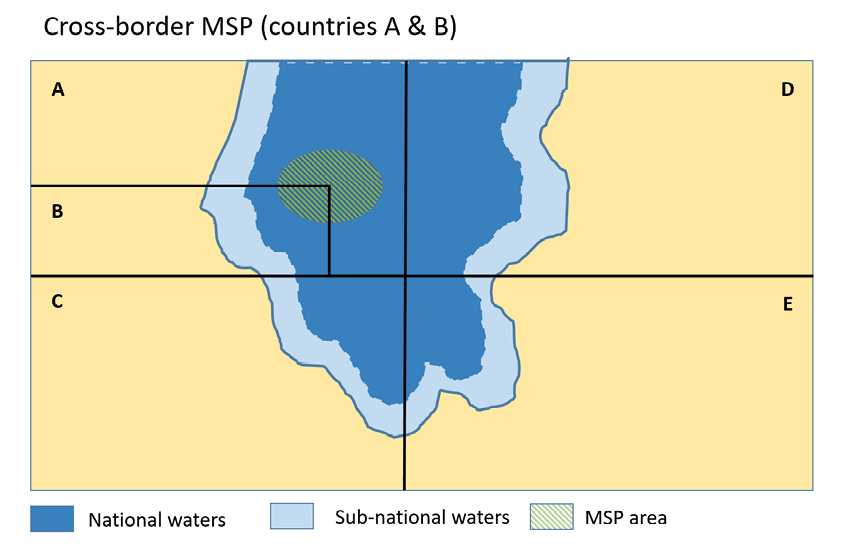

MSP across an entire LME can have different levels of complexity as it spans across one or more shared borders (European Commission DG for Regional Policy 2011). The following definitions and diagrams provide clarification of various possible levels:

•Cross-border (Figure 5) refers to engagement between two or more entities that share a common political border (e.g. neighbouring countries). At times, there can also be disputes on the exact locations of these borders.

Figure 5: Cross-border MSP (two countries)

•Transboundary MSP (Figure 6) refers to engagement of multiple entities (e.g. countries, states, provinces) across one ecosystem, who also do not necessarily share a common border. Transboundary expands beyond transnational in that it encompasses sub-national (see below) as well as the high seas. Similar to transnational MSP, each entity has individual jurisdiction over different ocean spaces, different economic considerations, drivers for MSP, etc. For the purposes of this handbook, we refer to transboundary MSP as the most all-encompassing term, which captures various LME contexts.

Figure 6: Transboundary MSP (multiple national and sub-national entities)

In all cases, one has to further distinguish between:

•Sub-national where several different entities (e.g. regions, provinces) within one country each hold jurisdiction over marine waters which are relevant for an MSP plan in national waters. In the diagrams above, sub-national waters are indicated in light blue closest to the shoreline.

•Multi-national where several countries each hold national jurisdiction over a joint ecosystem.

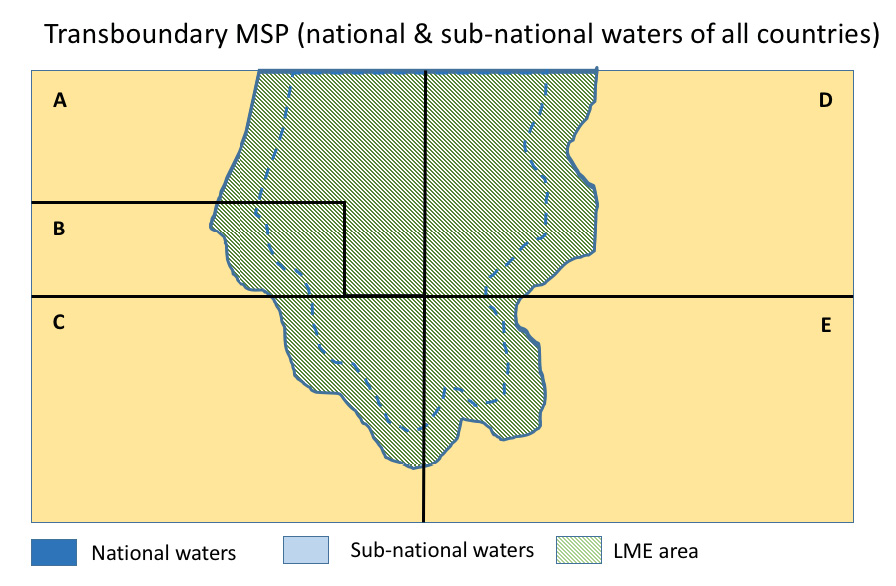

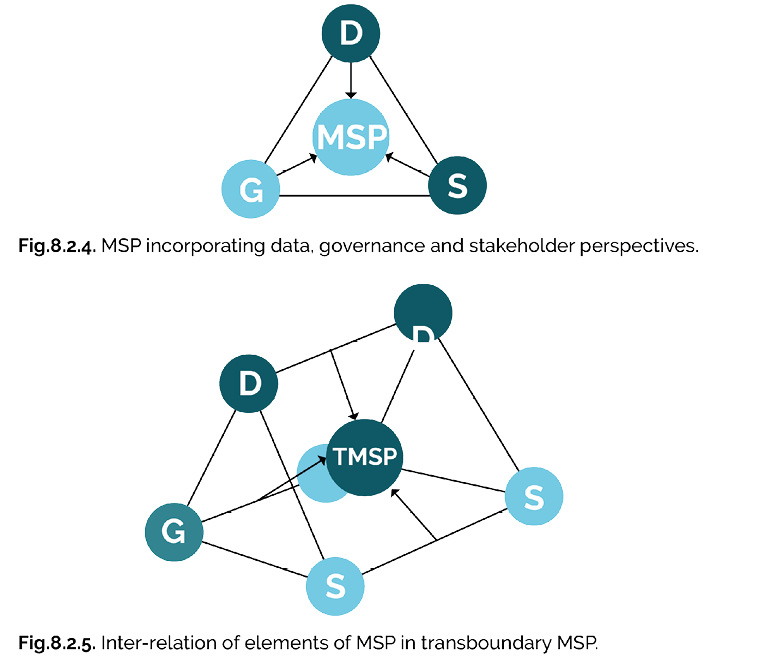

The level of complexity increases when not only different administrations (e.g. environment ministry, energy ministry, etc.) but also different countries are involved. As the legal basis and mandate for MSP is normally held exclusively at the national (or sub-national) level, MSP is by definition a political process, meaning that it requires decisions to be made in various governmental bodies to support, initiate, develop and ultimately implement MSP (Ehler and Douvere 2009). Figure 7 illustrates this added complexity in a transboundary setting, where elements of an MSP process need to be considered in relation to each other as well as across international borders.

Figure 7: Example of relationship between MSP elements in a single country (top)

and transboundary (bottom) context (Jay 2015)

Multi-national MSP implies agreement between two or more different political bodies from more than one country. Moreover, countries in a given multi-national context are normally at different stages of MSP implementation, if they have even begun a national MSP process. Additionally, planning cultures, economic conditions, stakeholders, legal mandates and interests may vary substantially within a particular MSP situation (please see further discussion in Ch. 5).

Given that most LMEs fall within the multinational context (e.g. multiple countries with jurisdiction over one ecosystem), our subsequent transboundary considerations, tools and examples are presented primarily with this context in mind. However, as MSP deals with integration challenges also in less complex situations - the toolkit can also provide useful ideas for any given MSP process.

Further discussion of issues of management area scale can be found in the Stategic Approach Toolkit in Chapter 3 section 3.4: The Spatial Variability of Transboundary Concerns and SAP Reforms and in the Governance Toolkit Chapter 4: Scale of Governance in LMEs.

2.2.3 Transboundary planning concepts: vertical and horizontal integration, spatial subsidiarity and the nested approach

MSP at the national level is defined as a process across sectors (horizontal integration) as well as across administrative and planning levels (vertical integration). These factors are relevant in a multi-national MSP context, with an added dimension: cooperation is required among the same sectors and administrative levels across countries (thus integration of different levels of government). Figure 8 illustrates the difference between multi-level, cross-sectoral and transnational, as a way to show the appropriate level at which stakeholders should be managed in these different dimensions (taken from the Baltic Sea context).

_Latvia_for_the_PartiSEApate_project._(xxxvii).jpg)

Figure 8: Multilevel paths in the Baltic Sea Region. Created by Baltic Environmental Forum (BEF) Latvia

for the PartiSEApate project. (Matczak et al 2014)

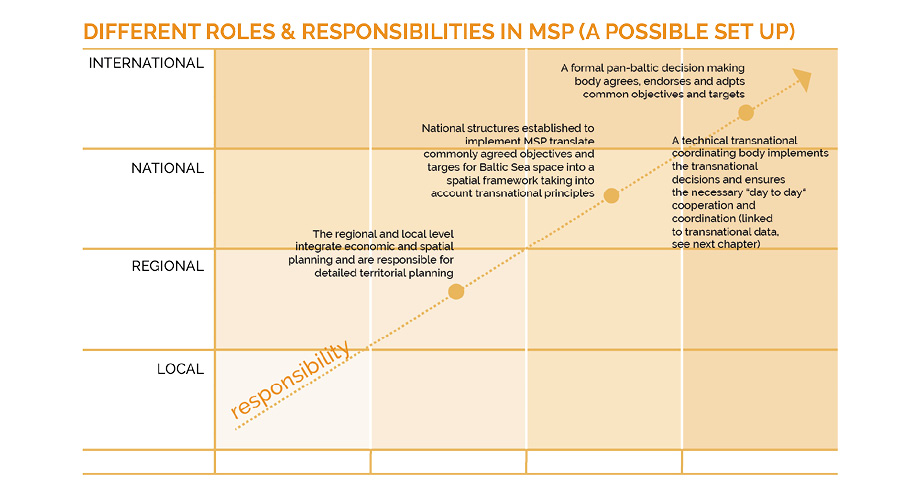

Given this multi-dimensional nature, transboundary MSP should adhere to the principle of spatial subsidiarity, which proposes that spatial challenges should be dealt with at the lowest most appropriate spatial level. However, this must be facilitated by appropriate structures and processes at national and international levels. These structures help to ensure that MSP is conducted as a cooperative practice involving several spatial and administrative levels, and the objectives for different levels are aligned. Figure 9 illustrates an example of a possible set-up of different roles and responsibilities in a multi-national, transboundary MSP context.

Figure 9: The spatial subsidiarity ladder in MSP, developed for the Baltic Sea Region (Schultz-Zehden. and Gee 2013)

To implement the spatial subsidiarity principle, many countries take a nested approach to MSP, where plans are organised in a hierarchical order, meaning that there are appropriate linkages across administrative levels (vertical integration). A nested approach to MSP is often appropriate for countries where there is divided jurisdiction between the national and local level, resulting in different plans created for different sea areas. These can be very detailed at the local level, and if done right, a nested approach to MSP could ensure planning coherence where all plans fit into each other.

Such an approach also respects the fact that currently there are limited instances where formal legal obligations exist to develop MSP plans at the national or transnational scale.3 Countries are therefore potentially faced with a situation, where they may not have a direct counterpart for MSP yet within their LME partner countries.

2.2.4 Results of transboundary MSP

With the above considerations for transboundary MSP in mind, it is therefore very likely that the result of a multi-national MSP may not be one single marine spatial plan covering an entire transboundary area (e.g. an LME). Rather, the end result is often a coherent set of national marine spatial plans within the LME, which are based on jointly developed outputs, namely:

1. a joint assessment of current conditions covering the whole LME (Ch. 5);

2. a forward-looking vision/strategy for the LME at hand (Ch. 6); and

3.mutually agreed upon guidelines and principles (Ch. 7).

Additionally, a multi-national MSP process could result in distinct ‘hot spot area’ plans, for specific locations spanning two or more national boundaries with high levels of activity or sensitive cross-border issues. (see further discussion on this topic in section 5.2)

2.3 No “one-size-fits-all” approach

There is, of course, no “one-size-fits-all” approach to marine management, and therefore not at any level of MSP. Something that has worked in one country or region may not be applicable to another region. Environmental conditions, maritime activities and related MSP issues differ substantially in marine areas around the globe. These can be specific to a given country not only due to socio-economic conditions and related interests in maritime activities; but also, due to the geo-political situation of the given country or region. Most obviously, the size and type of marine space available to each country is also variable.

Globally, countries are at very different stages of MSP development, with differing MSP resource availability and varying governance systems both for national processes as well as transnational cooperation. Moreover, planning cultures differ substantially, which impacts how a marine spatial plan is adopted in national legislation. In some cases, countries may focus on establishment of specific zones and exact allocation of maritime activities; whereas other countries may focus more on establishing principles and strategic planning criteria. The Table 1 provided in Example 2.3.1 provides a sample list of different types of plans developed as a result of an MSP process.

The examples provided in the following chapters of the toolkit include, where appropriate, a description of the context in which the tool or method is applied, rather than providing a “one-size-fits-all” approach. The descriptions include information on the tool itself, how it was used, what is needed to use it (i.e. enabling conditions), and the limitations or challenges of using the tool or approach.

2.3.1 EXAMPLE: Different types of MSP plans

Differences in planning cultures, legal mandates, governance systems, and other factors influence the end result of a given MSP process. The Table 1 summarises different types of existing MSP plans, showing the diversity resulting from MSP approaches and that a “one-size-fits-all” approach cannot be applied to MSP. This list is not intended to be exhaustive, and further examples of types of plans are likely to exist.

Table 1: Types of marine spatial plans

|

Type of Plan |

Examples |

Description |

|

National plan with spatial allocations |

Maritime Spatial Plan for the Belgian Part of the North Sea, |

This plan lays out principles, goals, objectives, and long-term vision, and spatial policy choices for the management of the Belgian territorial sea and EEZ. |

|

Belize Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan |

This plan covers both coastal and territorial seas of Belize and sets out action plans which are supported by zoning/spatial schemes for the management of coastal and marine human activities/uses |

|

|

Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan |

The plan is being developed in phases and takes a multi sector approach to zoning the entire EEZ for marine protected areas, and multiple uses in addition to an implementation plan. |

|

|

National integrated plan 4 |

Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth – an Integrated Marine Plan |

This sets out a roadmap for the Government’s vision, high-level goals and integrated actions across policy, governance and business to enable Ireland‘s marine potential to be realised. Implementation of this Plan will see Ireland evolve an integrated system of policy and programme planning for marine affairs. Harnessing our ocean wealth: an Integrated Marine Plan for Ireland |

|

National Framework for Marine Spatial Planning in South Africa |

The framework adopted in 2017, delivers high level directions for developing MSP in the context of existing legislation, policies and planning regimes in South Africa. It also sets out the processes for developing and implementing marine area plans to ensure consistency across the entire EEZ. National Framework for Marine Spatial Planning in South Africa |

|

|

Multi-level plans |

Sweden |

Three distinct plans for separate areas, covering the territorial sea from 1 nm outward of the base line and the EEZ, are under preparation by the same national authority; while coastal regions also have the right to prepare their plans up to 12 nm. |

|

China |

The Law of the Management of Sea Use (Li 2001) in China established a hierarchical marine functional zoning (MFZ) scheme at different scales including national, provincial and municipal/county level. The national marine zoning is used to address quantifiable national objectives/zones and the experience informed the development of 11 MFZ plans for coastal provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities by the respective local governments. The provincial MFZ divides the national MFZ into sub zones whiles the municipal/county level MFZ divides the provincial MFZ into more specific and smaller zones where necessary. |

|

|

United Kingdom |

In the UK, the preparation of marine plans is the responsibility of the respective governments within the UK. For example, Scotland has prepared Scotland’s National Marine Plan, which provides a single framework for managing Scotland’s seas. This plan will be supplemented by eleven Regional Marine Plans, prepared by the Marine Planning Partnerships. |

|

|

Germany |

There is no hierarchy between the different plans prepared for the two EEZs (Baltic Sea and North Sea) and the three plans prepared by each of the coastal states; e.g. the plan prepared by Mecklenburg-Vorpommern for its 12 nm zone is not under a hierarchical order of the plan prepared by the Federal Government for the Baltic Sea EEZ. |

While MSP has a substantial focus on the spatial dimension of various human activities and ecosystems, a map which indicates the location of current uses and conditions is not the only intended end product of an MSP process. Rather, it is the starting point (referred to as the ‘stock-take’, see 5.7), regardless of the geographic scope of an MSP process (e.g. national, sub-national or multi-national).

An MSP plan can contain a map with 1) clear designated areas for current uses and 2) indicate possible/planned areas for future uses. In addition to such a map, or multiple maps, an MSP plan is likely to include planning policies to guide future developments. A plan is designed to resolve both current conflicts as well as prevent future conflicts and foster synergies between uses. Accordingly, a future-oriented vision and corresponding goals and objectives should be included in a plan. These then point towards suitable locations for uses, taken from an integrated perspective. Please see example 2.4.1 for a description of the contents of a sample MSP Plan.

Additionally, the positive impact of an MSP process may not only stem from the resulting plan itself. An MSP process may have numerous positive side effects, as it often provides an initial forum where different stakeholders express their given interests (‘stakes’) related to a specific maritime space. If well designed, an MSP process may lead to increased understanding of other stakeholders’ needs, and thus not only potentially limit conflicts, but create synergies and cross-sector cooperation fields, which may be outside the scope of the actual spatial planning dimension as such (e.g. economic cooperation).

Along these lines, it should be clarified that MSP cannot be the single tool to bring about all solutions to management challenges in a given marine space. In many cases, conflicts may be less about finding the appropriate location for an activity, but more about the actual way a maritime activity is carried out (e.g. certain types of fishing gear which may damage habitats) or even about whether a maritime activity is carried out at all. Even though MSP plans may sometimes address such principles in relation to spatial dimensions of uses, determining an alternative method for how to conduct an activity may often be well beyond the actual mandate of the MSP authority. Rather, alternative methods often need to be agreed, endorsed and implemented by separate regulatory authorities based on national legislation and structures.

In cases where any decisions may lead to increased costs or even the reduction of a given use in a maritime space, MSP therefore involves political decision making (as referenced in the IOC/UNESCO definition of MSP). Understandably, agreement on such trade-offs is even more difficult to achieve between countries.

As a result, initial MSP processes should not necessarily start with the most debated issues, but with those where ‘easy wins’ can be achieved within a relatively short time frame. It is important to keep in mind that MSP also incorporates the concept of adaptive management, and thus should not be thought of as a one-time process. Rather, it is an iterative cycle, which should be revisited and reconsidered according to an agreed time frame – allowing for consideration of more complex, controversial and emerging issues in a later ‘turn’ of the cycle and ‘next generation’ MSP plans.

2.4.1 EXAMPLE: Sample contents of an MSP plan (England)

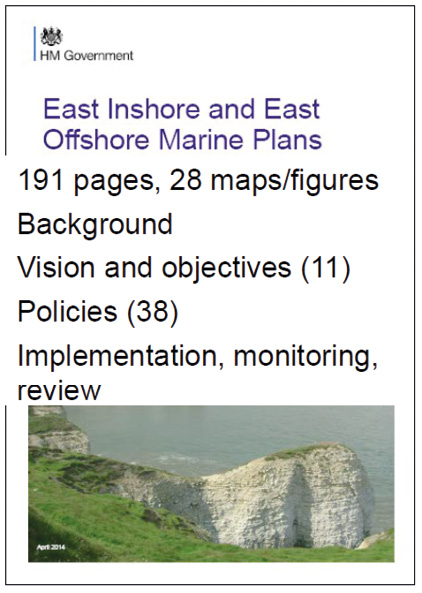

An MSP plan is likely to contain more than just a map of current uses – rather, it can also include policies to guide future oriented development. For example, England’s Marine Management Organisation (MMO) has jointly developed marine plans for two regions to date: The East Inshore and East Offshore marine plans. The plans contain 28 maps and figures, as well as 11 objectives and 38 supporting policies (Figure 10). While the maps help marine users understand the best locations for their activities, future developments are guided by the priorities and policies laid out in the plan for the specific plan area.

Figure 10: Number of maps for UK East Inshore and East Offshore Marine Plans. Source: Presentation by Paul Gilliland at 13th Meeting of the EU Member States Expert Group on MSP, 11-12 October 2017