7. Solutions, Planning and Implementation

There are very few cases where a transboundary MSP process has already gone through a complete planning cycle and has therefore led to a concrete set of planning solutions – let alone binding implementation.

In general, it should be noted that planners themselves often do not have the mandate to solve all issues and that further political involvement is required if sensitive conflicts are to be resolved and plans and recommendation put into practice.

Planners have the capacity, however, to identify key issues, which can then be redirected to the right bodies responsible for handling them. It is mainly on this basis, that some samples can be shown of what kind of planning solutions may be found for transboundary MSP areas, and how they can be eventually enforced, despite being governed under different jurisdictions.

7.1 What type of planning solutions?

A distinction has to be made, whether planning solutions for transboundary MSP relate to

a)joint management measures in a concrete, specific set of cross-border, joint planning areas (hot spot areas – see 5.2.4); or

b)a common approach on how the regulatory provisions, e.g. zones, of the maritime spatial plan(s) are defined throughout the whole , transboundary area

c)an agreement on how countries integrate issues of transnational concern into their national MSP plans (potentially to be adopted later on), and thus potentially adapt planning decisions according to transnational needs; or

d)more general agreements on the overarching MSP governance system within the given LME; referring to mechanisms of how countries decide to collaborate and consult each other in MSP processes in the future. This could take the form of adhering to a joint set of planning principles, cooperation as well as consultation mechanisms including joint strategies on how to ensure finance for future joint initiatives (e.g. set up and maintenance of joint MSP data infrastructures or enabling tools to carry out cross-border Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) processes).

All those different forms of transboundary MSP are applicable for MSP in transboundary LMEs. It highly depends on the given context whether solutions will initially be found for a specific focus-area, or whether to begin with the establishment of a suitable transboundary MSP governance system.

In many cases, MSP may also be established as a new tool within an already existing governance system. This has the advantage that MSP may immediately be able to concentrate more on the actual solutions for a given issue (please see examples 7.1.1, 7.1.2 & 7.1.3). Further discussion on strategic planning is included in the Strategic Approach Toolkit Chapter 3 on SAPs and in the LME Project Cycle Toolkit Chapter 4: Preparation of Strategic Action Programme (SAP) Projects.

Given different planning cultures across countries, an existing governance system may put more focus on achieving coherence between planning provisions for MSP, but may be less prone to enable similar types of planning provisions. As shown earlier, plans throughout Europe for instance differ substantially in view of how planning provisions are integrated into the given national framework (see 2.3.1). Whereas this does not necessarily mean that the plans are not coherent with each other, transboundary cases with similar zoning systems seem to be mainly applicable in areas within one country (e.g. Germany, Australia – please see examples 7.1.4 & 7.1.5). In other cases, MSP as such first needs to be established.

7.1.1 EXAMPLE: Adapting existing management measures (CCALMR)

CCAMLR is a successful example of common management of one large marine area which is governed by different states. Its existence was driven by the need to find a multi-lateral response to a history of over-fishing in the Southern Ocean and increased threat of unregulated fishing on krill. CCAMLR has established a joint management of (de facto) high seas by all CCAMLR Convention Members (primary). It has also managed to establish a regime where respective coastal members are bound to transpose jointly agreed conservation measures in their own maritime zones, which belong to the CCAMLR Area.

►Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCALMR)

7.1.2 EXAMPLE: Piecemeal approach through adoption of rules and agreements (CTI-CFF)

The focus of the CTI-CFF was to designate “priority seascapes” and MPAs, apply the ecosystem approach to the management of fisheries and climate change adaptation measures between 6 countries in the western Pacific Ocean. The initiative did not initially start with an agreed plan and mechanism for implementation.

Socio-economic differences across the Coral Triangle countries was a challenge for an agreement to be made at the inception of the initiative (e.g. Papua New Guinea was slow to ratify the Secretariat Agreement on financial grounds). However, the CTI-CFF prioritised the agreement on goals and a plan of action in 2009, before committing to implementation through the adoption of the Rules of Procedure and Secretariat Agreement two years later. The initiative is a good example of how broad LME goals and plan of actions developed can be given cooperative and legislative backing for implementation overtime.

►Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI- CFF)

7.1.3 EXAMPLE: Joint management measures (Rhode Island)

The ‘Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan’ was developed over a course of a two-year period and has been formally adopted by the relevant authorities in 2011. Apart from the push from the offshore wind energy industry as an MSP driver, the case was also strongly enabled by the fact that it is NOT a multi-national case and thus had a strong and clear framework as a foundation. The plan enabled designation of areas of particular concern as well as restricted use areas (esp. for offshore wind energy deployment) in an integrated way across the two states concerned (Rhode Island and Massachusetts), including even designating a joint area of mutual interest. It is therefore a concrete case where a joint plan has been adopted across two different jurisdictions for a hot spot area. The adoption of the plan has in turn also achieved its goal: it has led to the successful development of the first offshore wind farm in the US, without leading to substantial conflict with other users (e.g. preventing conflicts from happening).

►Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan

7.1.4 EXAMPLE: Complementary zoning (Great Barrier Reef)

While MSP in the Great Barrier Reef has been applied in only one country (Australia), the sheer size of its application and the fact that it is used across differing jurisdictional arrangements, actually means that it also can serve as an example of a transboundary approach to MSP. Already by 1979, the Australian and Queensland Governments agreed to complementary management of the waters and islands within the GBR Region. Known as the Emerald Agreement, this was fundamental in order to clarify the jurisdictional complexities of what was deemed State Waters (extending from high water mark to 3 nm offshore) versus ‘Commonwealth waters’. As a result, the State of Queensland ‘mirrored’ the federal zoning in nearly all the adjoining State waters. The result is that today there is a complementary zoning for virtually all the State and Federal waters across the entire GBR from high water mark out to a maximum distance of 250 km offshore. This provides for more effective marine conservation and public understanding of the entire area as the regulatory provisions are the same irrespective of which jurisdiction applies (Day 2015).

7.1.5 EXAMPLE: Traditional Owner Agreements (Great Barrier Reef)

As one element of the complementary management approaches to the various MSP layers and zoning regimes within the Great Barrier Reef; formal Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreements (TUMRAs) describe how indigenous Traditional Owner groups work with the Australian and Queensland governments to manage traditional use activities in their sea country. TUMRAs support cultural practices while protecting species and ecosystems critical to the health of people, culture and country. The TUMRAs operate across the jurisdictional boundaries and have been developed with differing levels of governments, and with various industries, stakeholders or community groups (Day 2015)

7.2 How to move from analysis to joint solutions

The analytical stage is mainly designed to develop a more concrete understanding on the specific “hot spot areas” as well as potentially “hot spot issues”, for which it is necessary to find transnational planning solutions (see 5.2.4 for more on hot spots). Based on matrices of interests, it is possible to identify where countries’ interests in a given location may:

•Co-exist (no further action necessarily required other than status quo); or

•Be in conflict with each other (requiring further action – if possible); or

•Enable each other (potential action to strengthen joint interests).

It is important to highlight the positive element of building on joint interests rather than only focusing on potential conflicts.

It is easier to come to a more pragmatic understanding of possible solutions when the area in question is concretely defined and there is a high level of understanding of underlying interests among the planners and countries involved (see 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, 5.5). At the same time, it should be noted that a solution may not be possible in all instances at the level of planning authorities, and that issues may need to be moved to a higher political level for resolution. Even in such situations, it has proved to be already helpful when planners across borders have gained a better understanding of the given issue and may at least already have developed either one or several options on how the issue may be solved by the political level. Further discussion on appropriate institutional arrangements for implementation can be found in the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit Chapter 4.2.3.3 Co-management approaches and 4.2.3.4 Seeking and implementing agreements and policies.

7.2.1 EXAMPLE: Identifying issues and suggested solutions for issues arising in transboundary hot spot areas in the Southwest Baltic Sea (Baltic SCOPE)

As described earlier (see 5.2.5), planners identified six specific focus areas within the southwest Baltic Sea, that are important form a transboundary perspective and that require cooperation between the involved states. For all areas, national planners and stakeholders identified and highlighted the main areas of potential synergies and conflicts in the region as well as other issues that require cooperation. This was achieved through the development of topic papers, a matrix of national interests (see example 5.5.3) and broader discussions within the project’s planners’ meetings, national stakeholder meetings and in a transboundary stakeholder conference. Following issue identification, national planners identified solutions and formulated recommendations to address conflicts and promote potential synergies in the transboundary focus areas and across sectors. This was achieved through open discussions within trilateral and bilateral meetings as well as unilateral tasks assigned to specific project partners.

Given the different nature of these areas and the resulting varying conflicts arising between the different countries involved; the types of planning solutions suggested also differ substantially. The full set of conflicts, potential synergies and related solutions (as well as more detailed description of methods used) are to be found in the case study report from the Baltic SCOPE project (Baltic SCOPE 2017).

The following only provides for a snapshot of what kind of solutions can actually be found in order to ensure coherence between plans within the larger southwest Baltic Sea ecosystem:

•The possibility to connect linear infrastructure in the transboundary area should be highlighted and developed in national plans;

•All countries should secure access of the given hot spot area to their fishermen by considering routes to their main fishing and landing ports;

•Involved countries should, in cooperation, consider to reroute the ferry or other shipping lanes before allocating space and/or building offshore wind farms in the identified hot spot area;

•Countries need to consider how offshore wind farm interests affect important fishing areas used by all countries;

•Offshore wind farm requirements in the given hot spot areas should be harmonised between countries before permits are granted; and/or

•Develop a shared visualisation tool designed to increase knowledge and understanding of current & future conditions in some hot spot areas

Moreover, the project suggested to develop additional tools, which would enable transboundary planning across the whole Baltic Sea Area:

•Development of a joint fisheries map which should provide evidence and activities of fisheries in their national waters as well as across the whole Baltic Sea

•Planning and sector authorities should collaborate to map the areas of high ecological value across the Baltic Sea using both a harmonized methodology and data sets in order to create MSP relevant green infrastructures/blue corridor GIS-layers to be used in MSP

7.3 Implementation and Enforcement

As discussed previously (7.1), implementation and enforcement in a transnational context highly depends on the existing governance regime. In areas where all countries already have MSP processes in place, implementation may mainly relate to (voluntary) agreements by countries to adhere to some strategic planning criteria or principles within their national MSPs.

However, the absence of existing MSP regimes at the beginning of the transboundary MSP process may also entail a unique opportunity, in that subsequent national MSPs in each country may be aligned with one another from the very outset. As shown by the given example of the MSP governance structure within the Baltic Sea Region, continuous dialogue between the respective MSP authorities is crucial, as well as a transparent governance structure that supports alignment of strategic LME wide objectives (top down) with more regional, lower scale planning processes (bottom-up) (please see example 7.3.1). For more on effective governance, please see the Governance Toolkit Chapter 5.1 Effective Governance.

On top of national structures as well as transboundary agreements to ensure coherence through consultation and cooperation during preparation of national and sub-national plans, a transnational MSP coordinating body needs to be set up which is tasked with organising and ensuring implementation of these agreements. This coordinating body should be responsible for drawing up transnational objectives and targets for the LME, requirements for tailored monitoring as well as continuous development and improvement of related transnational tools (such as joint data and research programmes). Further discussion on coordination mechanisms for implementation is included in the Stakeholder Participation Toolkit Chapter 4.2.3 Involving Stakeholders in Implementation.

7.3.1 EXAMPLE: Establishing a long-term MSP governance structure (HELCOM-VASAB MSP working group)

In the Baltic Sea Region, countries have established the HELCOM-VASAB MSP working group as an on-going cooperative structure, where countries continuously exchange and deepen working relationships to ensure that their respective MSP processes are aligned with each other. Over the course of the last several years, the character of the group has evolved. At the time it was created, not all countries had MSP legislation or authorities in place. Therefore, the group was designed to ensure that such processes are put into place. Currently, it is the coordinating body where the given MSP authorities – by now in place in all countries – meet and continuously work on improving alignment between MSP processes.

Starting from agreement on ‘joint principles on MSP’ followed by the adoption of the joint MSP Roadmap - which stipulates that all BSR countries should have MSPs in place by 2021 - the HELCOM-VASAB MSP WG has by now also adopted a series of ‘non-binding’ guidelines on a continuous update of country information; the ecosystem-based approach in MSP and transnational consultation and cooperation, as well as public participation on MSP. Moreover, the members of the HELCOM-VASAB MSP WG continuously engage in various forms of MSP cross-border projects, which create the basis for even stronger joint collaboration on MSP – such as the creation and ongoing maintenance of a transnational MSP data infrastructure as well as the development of guidelines on how to align and consult on pan-Baltic linear infrastructures.

Collaboration on MSP within the Baltic Sea Region has benefited from a strong tradition of collaboration and existing transnational cooperation structures (incl. HELCOM and VASAB) coupled with the general joint understanding that action is required to improve environmental conditions. This has been reinforced during the past few years, not only by many countries becoming EU Member States, but also by the creation of a macro-regional strategy, which is accompanied by transnational funding programme availability. This funding has enabled the implementation of a continuous series of MSP projects building on each other’s results.

These projects have created a strong community of MSP experts, who trust each other and have led to an underlying joint understanding of general MSP principles – even though they may have not been adopted formally by countries.

►HELCOM-VASAB MSP Working Group

7.3.2 EXAMPLE: Adapting management measures

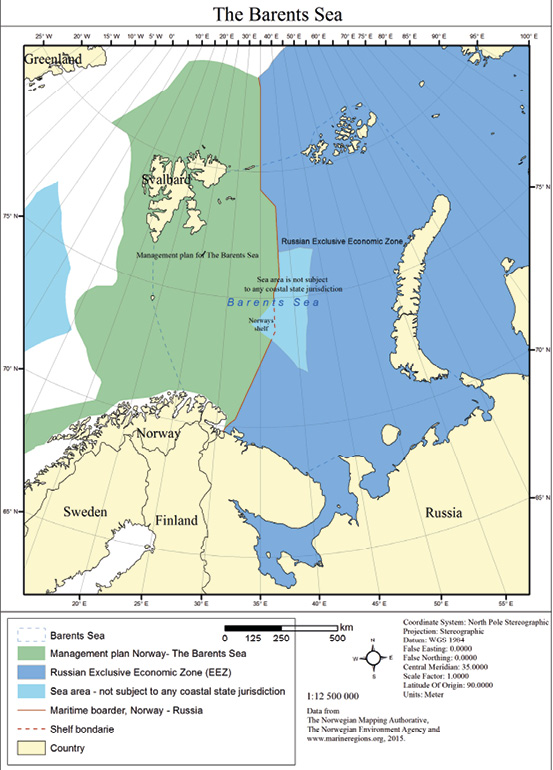

(Norway – Russia Barents Sea)

The Barents Sea is considered as a single LME that is divided by the border between Norway and Russia. The resolution of the disputed border between Norway and Russia in the Barents Sea and various cooperation structures have contributed to developing and adapting joint management measures in the Barents Sea by both countries.

For example, the Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission was formed as a cooperation mechanism to ensure healthy state of fish stocks in the Barents Sea. Joint management measures such as total allowable catches (TACs) and technical measures for fish stocks such as haddock, capelin and Greenland halibut, and beaked redfish are jointly agreed and reviewed based on management strategies agreed by both parties and on recommendations on catch levels from ICES, which includes both Norwegian and Russian scientists. Policies and joint management decision for fisheries are also informed by years of joint and advanced marine research cooperation between the two parties.

Figure 48: Map of Norway-Russia Barents Sea area

Similarly, there also exist bilateral agreements and joint contingency plans between the two countries on combating oil spills in the Barents Sea. However, the Barents Sea still poses new safety challenges and Russian cold climate experience can be merged with Norwegian offshore competences. The Barents 2020 project (Norway-Russia)

through industrial cooperation have assessed international standards for safe exploration, production and transportation of oil and gas in the Barents Sea, based on existing standards in the North Sea. The output of the project included recommendations and guidance to improve ISO 19906 as an Arctic design standard; best practice for ice management; recommendations on evacuation, escape and rescue and recommendations on working environment.

The long-term goal is for all these structures, management measures, cross border research and projects such as the Barents 2020 to inform transboundary MSP cooperation between the two parties where Norwegian and Russian MSP plans for the area are closely aligned. Norway’s experience of developing integrated management plans and the results of the bilateral cooperation on the marine environment will be key parts of the MSP process that Russia is now planning. The joint management measure and actions for fisheries and international standards for safe exploration will be adapted and inform the aligned marine plans.